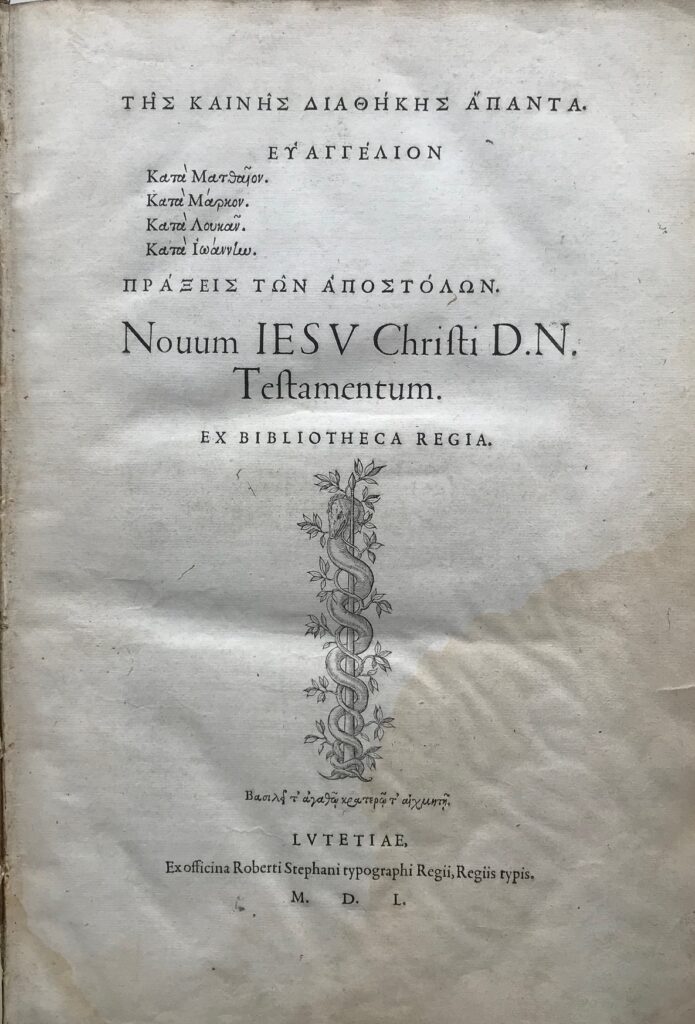

Mark McKillion, Ulster University MA History graduate and volunteer for the Library in 2022, carried out research on Robert Estienne’s New testament Tēs kainēs diathēkēs hapanta : Euangelion. … (1550) (object ID P000985194).

You can adopt this book for £250, and support the work of the Library, caring for our wonderful collections, and inspiring present and future generations!

The unique circumstances behind the evolution of the New Testament are highlighted by J.H. Morgan, who notes that it would only be until the discovery of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri manuscripts by Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt that the text could be translated into Modern Greek.[1]

Edgar V. McKnight corroborates this further by stating that prior to the 19th century, it would have been considerably more difficult to reach a consensus regarding the influence of Biblical Greek on the development of the Greek language: after the discovery of the manuscripts, Nigel Turner puts forward the argument that Biblical Greek was developed to accommodate for its use as a component of the Scriptures as well as a common spoken language, therefore granting it great significance “at a time when men are finding their way back to the Bible as a living book and perhaps are pondering afresh the old question of a ‘Holy Ghost language.'”[2]

One of the most notable figures during this transitional period would be Robert Estienne, a 16th century French printer and scholar: Hans R. Guggisberg provides a short summary of his publication of the Greek New Testament by noting that it was part of a larger series of theological texts published by Estienne throughout the early 1540s, including Hebrew translations of the Pentateuch and the New Testament, with King Francis I directly providing him with financial support for his efforts.

During this period, however, Estienne’s scholarly achievements would be placed under scrutiny by various groups such as the Catholic theologians of the Sorbonne, who sought to censor the works of any Protestant writers situated in France, which they perceived to be antithetical to the teachings of the Holy Scripture. Nevertheless, Estienne persevered in his work as a printer, as he continued to work and on and refine his existing Bible editions and dictionaries, and eventually, his Greek New Testament would be published without incident, likely with the approval of the King of France himself.[3]