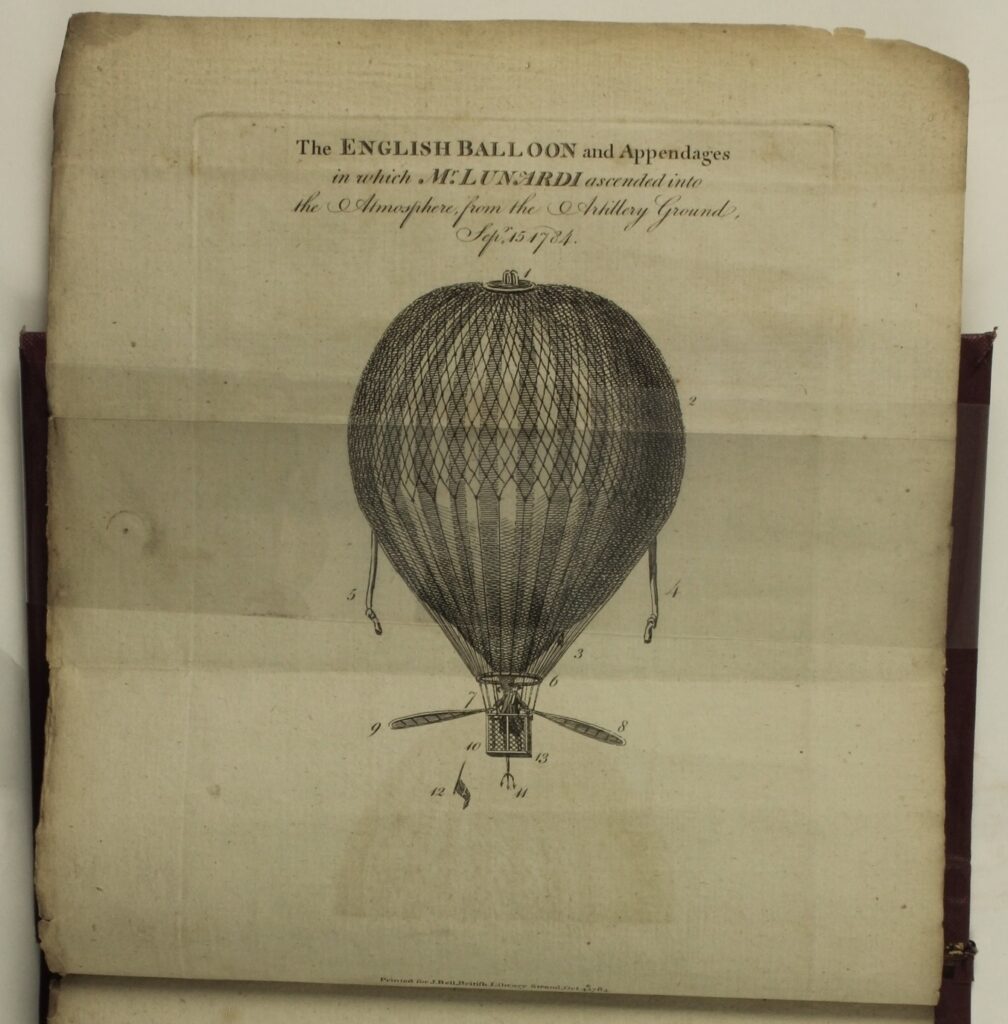

Mark McKillion, Ulster University MA History graduate and volunteer for the Library in 2022, carried out research on An account of the first aërial voyage in England (1784) (object ID P001406570).

You can adopt this book for £250, and support the work of the Library, caring for our wonderful collections, and inspiring present and future generations!

Vincenzo Lunardi’s enthusiasm for conducting research in the field of aeronautics is firmly established in his text An Account of the First Aerial Voyage in England. The account is a collection of letters in which Lunardi declares his intent to provide his own contributions to the development of aerial voyages throughout Europe, stating that other researchers before him were likely to be overcome by “the breath of fame, and the imaginary advantages to attend them, [which had] rapidly and plausibly multiplied.

Lunardi’s statement is corroborated by the fact that throughout the 1780s, the use of balloons for aerial flight had become a business in England. When Lunardi himself took his first voyage on 15th September 1784, the upper-class society in London would spurn him due to his reputation as a womaniser, where despite his popularity with the general public. Furthermore, when Lunardi and his fellow aeronauts were faced with the potential threat of “some restriction [being] laid on the madness of their frequent trips to the air,” they would start to favour a more competitive market by introducing various campaigns such as inviting the public to “to judge of the probable efficacy of the invention in question.”

[1] Keen, “The “Balloonomania”: Science and Spectacle in 1780s England,” pg. 511-513.

Because of the ever-changing nature of aeronautics, Lunardi would have had to rely on his own talent and resources in order to commit to his reputation among the British public as “that enterprising foreigner.” In fact, Lunardi himself refers to an extract from The Morning Post which summarised his beliefs regarding adapting to the increasing expectations of his audience. He notes that “discoveries beyond the reach of human comprehension at present, may by perseverance be accomplished, [and therefore] he who shrinks from innovation is not his country’s friend.”

Likewise, Keen corroborates Lunardi’s theory by referring to similar developments made by various aeronauts during this period: four months after Lunardi’s first flight, the Amercian physician John Jeffries would make his journey across the English Channel on 7th January 1785, following which he would make a scientific breakthrough in understanding the concept of flight, whereby other aeronauts would be gifted with corked bottles of “pure air, for the purpose of making experiments when on Earth,” with the October 1785 issue of Monthly Review eagerly anticipating the potential for aerostatic vehicles to be adapted for the pursuit of philosophical and scientific discoveries.[1]