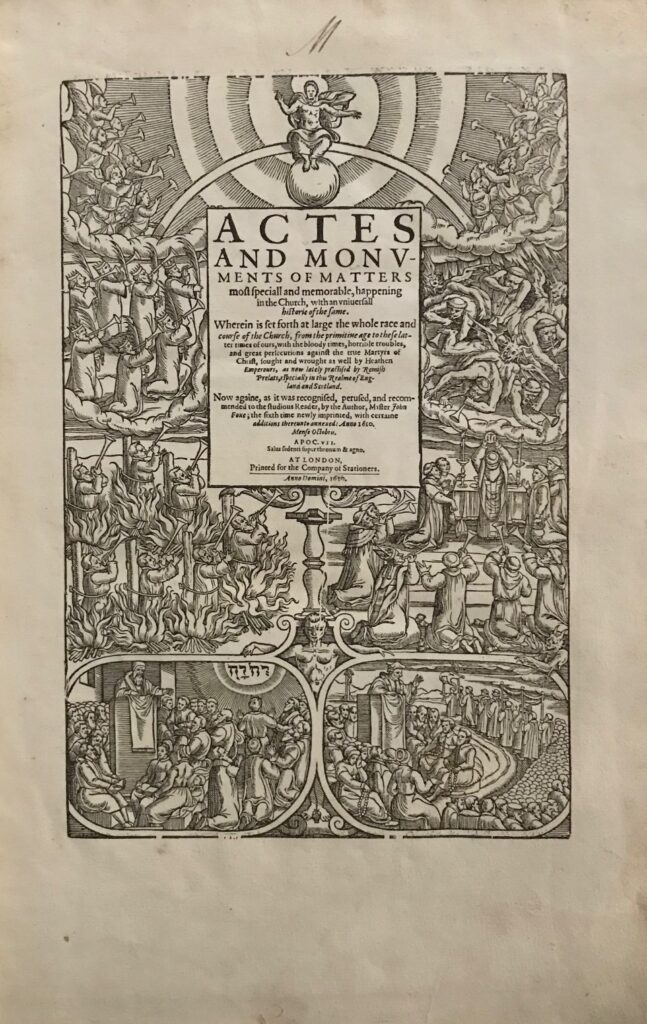

Mark McKillion, Ulster University MA History graduate and volunteer for the Library in 2022, carried out research on John Foxe’s Actes and monuments of matters most speciall and memorable, happening in the Church, with an universall historie of the same…. [Book of Martyrs](object ID P001412163).

You can adopt this book for £250, and support the work of the Library, caring for our wonderful collections, and inspiring present and future generations!

Throughout the Actes and Monuments, John Foxe applies an underlying moralistic subtext to his accounts of English history, as he compares the figures he perceived as noble martyrs for the Protestant faith who had faced their deaths at the hands of their Catholic persecutors with dignity, stating that “they all forgave and prayed for their enemies; no murmuring, no repining was ever heard amongst them.”

John R. Knott notes that Foxe drew upon the earliest Christian martyrs for his accounts, they would undergo several violent tortures as inspiration, such as “stripes and scourgings, drawings, tearings, stonings, plates of iron laid into them burning hot … gridirons, gibbets and gallows,” whereupon the vulnerable human body is separated from the inviolable spirit and allows the victim to transcend his or her physical pain by communing with the divine.[1]

Therefore, it can be inferred that Foxe was more interested in the moral and spiritual nature of martyrdom in Actes and Monuments rather than outright romanticising the physical tortures that the Protestant faithful would be subjected to, as suffering and pain was not necessarily a direct path to Heaven but rather “a trial of faith sent by God and as something to be endured and overcome through faith with the help of grace.”[2]

One of the most notable examples of this within the text is Foxe’s accounts of the ordeals suffered by Elizabeth I during the reign of her Catholic half-sister, Mary I, which appeared to take inspiration from contemporary sources. For example, a Venetian ambassador’s account of Queen Mary’s ascension to the throne states that “whereas until then she had shown [Elizabeth] every mark of honour, especially by always placing her besides her when she appeared in public, so did she now by all her actions show that she held her in small account.”[3]

[1] Knott, “John Foxe and the Joy of Suffering,” pg. 721-724.

[2] Netzley, “The End of Reading: The Practice and Possibility of Reading Foxe’s Actes and Monuments,” pg. 189.

[3] Freeman, “‘As True a Subject Being Prisoner’: John Foxe’s Notes on the Imprisonment of Princess Elizabeth, 1554-5,” pg. 104-107.