Ian Campbell Ross

(Delivered on Thursday 23 November 2017)

In just one week’s time, we shall reach the exact date of the 350th anniversary of the birth of Jonathan Swift: 30 November 1667. This anniversary has already been celebrated in Ireland in several ways. A large international conference, entitled ‘Swift350’, took place in Trinity College Dublin, in early June. A short lecture series was held in the Royal Irish Academy; a conference took place in Newbridge House, Portrane; and last week Professor Moyra Haslett of QUB spoke on ‘Swift and the North’ in the Linen Hall Library in Belfast. There have been exhibitions on Swift in, among others, the libraries of Trinity College, in Marsh’s Library, in the Royal Irish Academy, and the Dublin Public Library in Pearse Street. A series of events is being held this autumn in St. Patrick’s Hospital and tonight also sees the opening of first Dublin ‘Jonathan Swift Festival’, taking place over three days.

The Swift350 conference was an academic affair, with literary scholars and historians speaking on topics that, however interesting to specialists, would not perhaps have immediate appeal or even be readily comprehensible by the majority of readers, even those whose reading includes the work of Jonathan Swift. So, since there were parallel sessions, conference goers could opt to hear papers entitled ‘Natural Law and Thomism in the Allegory of A Tale of a Tub’ or ‘Swift, the Oxford ministry, and the search for ecclesiastical preferment, 1710-1714’; or ‘An uncancelled copy of Volume II, ‘Containing the Author’s Poetical Works’, of Faulkner’s 1735 Works of Swift’.

I hasten to say that I selected these examples, from others I could have chosen, because I know that each paper was well regarded by those who heard it – and, of course, the three papers did appeal to scholars with a particular interest in Swift’s philosophy or the Established Church at the end of Queen Anne’s reign or and bibliography.

The Dublin Swift Festival has a very different emphasis. It will take place in the Liberties, home to Swift for many years. St. Patrick’s Cathedral will be illuminated; there will films; creative writing classes including a session on travel writing; ballads from Swift’s Dublin; and the opportunity to sit down in the cathedral itself to enjoy a candlelit dinner featuring authentic seventeenth-century dishes including buttered and seasoned eel; chicken fricassee; pickled cucumbers and peese porridge: all, alas, at a decidedly twenty-first century price.

It is entirely appropriate that Swift should be celebrated in such different ways in this anniversary year – and that he should be celebrated not only in Dublin but throughout Ireland, not least in Armagh, a location with which Swift had particular associations through his friendship with the Acheson family of Market Hill. No other Irish author of Swift’s time – and few authors of any time, anywhere – can boast a literary reputation as a major writer of world stature and retain a continuing presence in popular local and international consciousness.

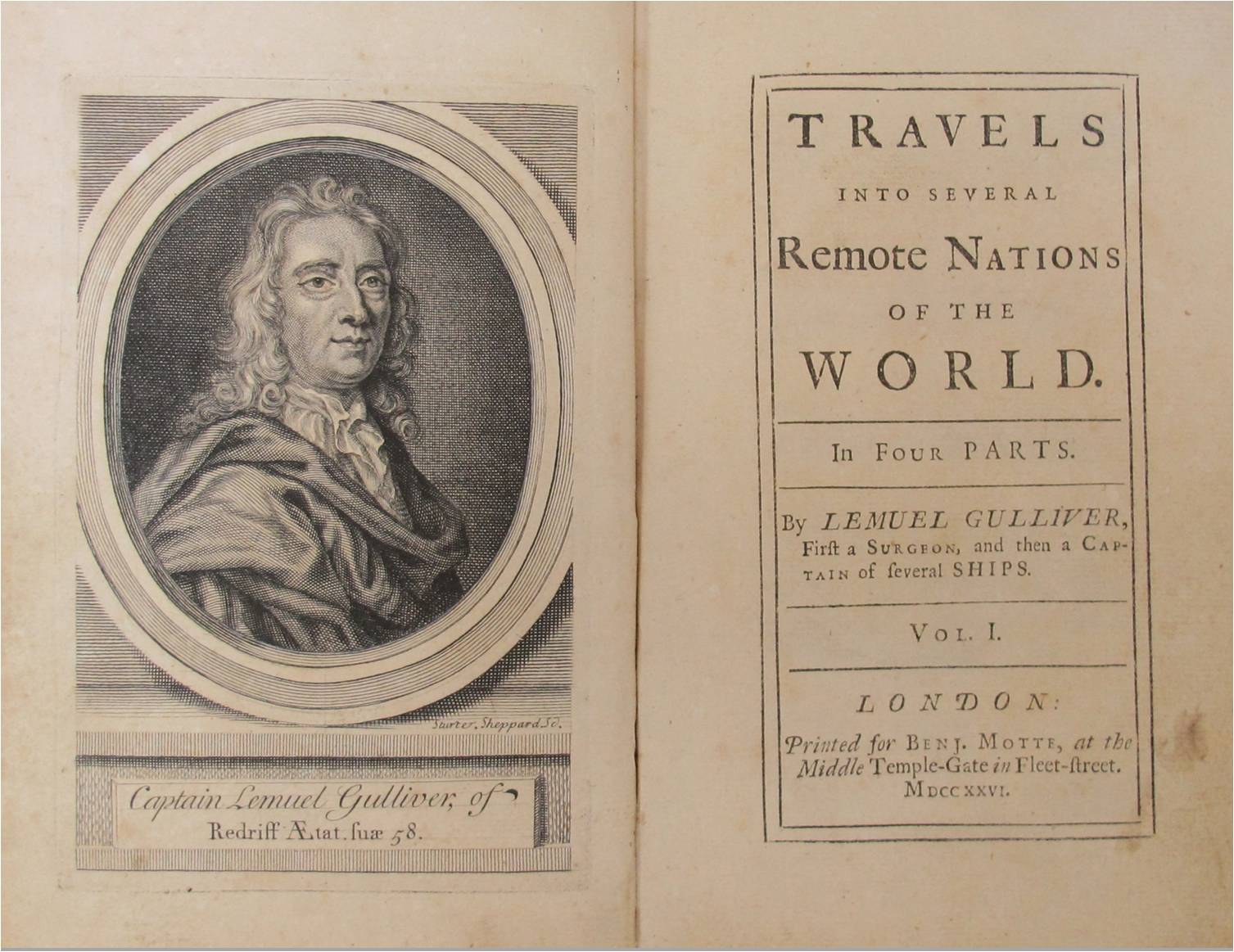

That reputation and the fact that Swift’s name is known to many who have read little if anything of what he wrote is due, above all, to his single most famous work: Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World or, as it quickly became known at home and later, in many remote nations of the world, Gulliver’s Travels.

Gulliver’s Travels is, beyond doubt, the most widely known work ever written by an Irish author or written in Ireland itself. First published in 1726, it has never been out of print, and has appeared in countless editions, sometimes complete, more often abridged and bowdlerized. Gulliver’s Travels has been, regarded as a children’s book (mistakenly so by some, but not by children) and translated into dozens of languages. It has been transposed for the stage, television and radio and adapted in a number of film versions, beginning as early as 1902 with Georges Méliès’s Le voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants.

More recent versions feature actors as well known as Richard Harris, Ted Danson and Jack Black. Less familar, perhaps, is the fact that Walt Disney turned Swift’s masterpiece into a vehicle for his own most famous creation, Mickey Mouse, in the 1934 cartoon, Gulliver Mickey.

And Swift’s presence in the cultural life of the past decades does not end there. Some of you here will remember the £10 note in the Republic’s Central Bank B series, in circulation between 1976 and 1993, which featured a portrait of Swift. (With a certain irony, Swift was replaced by the altogether less suitable James Joyce, who was as feckless with money throughout his life as Swift was fiscally cautious.)

Elsewhere, Swift has been honoured by postage stamps: in Ireland on several occasions but also further afield, as in the 300th anniversary issue in Romania in 1967 or in this year’s Hungarian stamp has lively and colourful image of Gulliver among the Lilliputians. If you live in Belfast, you can use the Lilliput laundry – founded over 130 years ago in Dunmurry – for your washing (your smalls, presumably). Should you follow Gulliver in taking a sea voyage, you can travel from Dublin to Holyhead on the Irish Ferries vessel, the Jonathan Swift.

And if you travel into other nations of the world, you can eat at restaurants, cafés and taverns, called ‘Gulliver’ in, among many others, Scotland, England, the United States, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Czech Republic, Russia and Italy.(Pizzeria named ‘Gulliver’ are found in numerous Italian cities for some unfathomable reason). In Hungary, Gulliver is honoured by an eatery that seems to offer something for each of his four journeys: a combined restaurant, pizzeria, coffee shop, and tearoom.

I looked unsuccessfully for a ‘Gulliver’ restaurant in China but the disappointment I felt at my failure to find anything was more than compensated for by the discovery that Chaoyang Park in Beijing has an inflatable statue of Gulliver that is the size of a 20-storey building and certified by the Guinness Book of Records to be the largest inflatable statue in the world.

Somewhat more serious examples of the way Swift and his creations have become known might include the ‘Drapier’ column in the Irish Times; the many ‘Modest Proposals’ which take their cue from Swift’s famous work of that title; the important influence he exerted on later Irish writers, including Laurence Sterne, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett; or, beyond Ireland, on books that draw on Swift’s writings, from one of the epigraphs to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale – taken from A Modest Proposal – to the title of John Kennedy Toole’s most famous novel, Confederacy of Dunces, alluding to Swift’s ‘Thought’: ‘When a true Genius appears in the World, you may know him by this Sign, that the Dunces are all in Confederacy against him’.

The subject of Swift in popular culture is an extremely rich one and I was fascinated myself by one of the papers given at the Swift350 conference in Trinity in June, by Dr. Ruth Menzies of Aix-Marseille Université, under the title of ‘Gulliver’s Travels in the World of Advertising’, which concentrated on the power of a single image from Gulliver’s Travels: that of Gulliver tied to the ground by the tiny Lilliputians, which occurs in publicity for quite different products in very different countries around the world.

A wonderful one from the nineteenth-century United States, shown by Dr. Menzies is for J. and P. Coats’ Best 6 Cord Spool Cotton (evidently strong enough to keep Gulliver tightly bound to the ground) and another, more modern if less easily comprehensible one, for a Ford 250 Heavy Duty Truck, dating from 2009.

What the 350th anniversary celebrations of Swift’s birth suggest to us, in other words, is both the continuing fascination that Swift holds for scholars, whether they be literary critics or historians, and the continuing power possessed by a tiny number of Swift’s works – or images from them – on the popular imagination.

In the remainder of this lecture I want to suggest the extent to which Swift himself consciously wrote for very different audiences, both learned and popular. And I want to suggest also that Swift, as a writer, initially shaped by the classical literature he was taught as a young man, learned to engage with his contemporaries in modern literary forms to which they could relate, while remaining ever conscious of a responsibility to contribute to a shared future that he often imagined with great prescience. Swift’s gaze, in other words, very consciously took in the past, his present, and a future of which we are a part.

I’ll begin with a paradox. The fact that we’re celebrating the 350th anniversary of Swift’s birth – Swift350 – has, it seems to me, had a somewhat perverse effect: that of diverting attention away from a very important aspect of Swift’s life. A moment’s reflection, of course, tells us that he was born in 1667. Yet the personal and literary implications of that simple fact are often overlooked. Swift is generally referred to, in critical as well as popular shorthand, as an eighteenth-century writer and is here celebrated as part of a Georgian festival.

There is nothing wrong in this: the bulk of Swift’s work was written and published in the eighteenth century and he died only in 1745, having lived through the reign of George I and the first eighteen years of the reign of George II. But it is important to remember that, born in 1667, Swift became reached maturity in the late-seventeenth century and was well into his thirties at the turn of the century.

It was in 1667 that John Dryden, a cousin of Swift’s, published Annus Mirabilis or The Year of Wonders, a poem celebrating English naval victories over the Dutch fleet in the year that also saw the Great Fire of London: 1666. It was a poem that confirmed the reputation Dryden had built up at the beginning of the reign of Charles II, whom he elaborately praised in such works as Astræa Redux: A Poem on the Happy Restoration … of his Sacred Majesty Charles II (1660) and To his Sacred Majesty: A Panegyrick on his Coronation (1661), poems that won for Dryden the posts of Poet Laureate – he was the first Poet Laureate – and Historiographer Royal.

In Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift, written when he was in his mid-60s and increasingly aware of his own mortality, Swift would refer ironically to his own age, putting into the mouths of others the dismissive sentiments:

He’s older than he would be reckon’d

And well remembers Charles the Second

(ll. 107-8).

Joking apart, however, Swift must in fact, have well remembered Charles II, since he was already 18 when Charles died in 1685.

Swift’s birth year of 1667 was also the year that saw the death of another great seventeenth-century poet: Abraham Cowley, the great English exponent of the Pindaric Ode: an elevated and ambitious verse form.

Swift’s career as a writer – and specifically as a poet – began when he was in his mid-twenties, with poems written under the influence of both Cowley and Dryden. Those early poems were not a success.

The earliest of all, the ode To the King on his Irish Expedition and the Success of his Arms in General (1691) was written in praise of William III, shortly after the Battle of the Boyne, and was intended by Swift to gain the king’s patronage. It was a work shaped both by Abraham Cowley’s reputation as a writer of Pindaric Odes and Dryden’s fondness for royal panegyric. Many years after Swift published his Ode to the King, when he had established himself, above all, as a satirist – a role by which he is most usually remembered today – he expressed a very different view of this kind of poetry. In his ‘Thoughts on Various Subjects’, published at the end of his life in the 1745 volume of Miscellanies, Swift declared: ‘All Panegyricks are mingled with an Infusion of Poppy’ (that is, they cause readers to fall asleep).

It was much earlier that Swift had been given a rude awakening in terms of thinking about his early attempts at verse, all of which were odes – either Pindaric (as Swift understood the term) or Horatian – and all intended to present Swift himself in the best possible light in order to ingratiate him with possible patrons, including King William and Sir William Temple.

Gallingly for Swift, it was the great John Dryden himself who told him bluntly: ‘Cousin Swift, Nature never intended you for a Pindarick poet’ – and after these early works, Swift took the advice to heart, learning to write in very different and modern poetic styles.

This was not, I think, an easy task for Swift but it was necessary if Swift was to reach an audience among his contemporaries, especially those younger than himself. It was John Dryden who wrote in 1700:

’Tis well an old age is out

And time to begin a new.

(Secular Masque, 1700)

Swift’s writing around the turn of the century shows him looking both backwards and forwards. The Battle of the Books, Swift’s short comic treatment of the contemporary debate, the ‘Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns’, supported the position of Swift’s then-employer, Sir William Temple, in giving preference to the Ancients – the great writers of classical Greece and Rome whom Swift had been taught to revere. The talent evident in Swift’s own contribution, however, suggested that modern writers might indeed aspire to rise higher than their predecessors, even if only – in a phrase Temple employed – because they were dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants.

The Battle of the Books, written in the late 1690s, was eventually published in 1704, along with the first edition of A Tale of a Tub. In certain ways, this work too looks backwards. The story of the three brothers, Peter (Roman Catholicism), Jack (Calvinism) and Martin (Lutheranism, and hence the Anglican Church, in which Swift was already a clergyman) had been used in the past as an allegory about Judaism, Christianity, and Islam; and the Tale frequently engages with mid-seventeenth century debates revolving around the skeptical philosophy of Thomas Hobbes.

Published anonymously, A Tale of a Tub is presented as a work written by a penniless, half-mad, hack writer, scribbling away in a London garret. Complex as it is, however – a series of digressions within digressions – contemporaries recognized a powerful and original mind. What they failed to recognize – and the fault may have been the author’s as much as that of his readers – was that Swift’s intention was to support the Established Church, not – as some contemporaries thought – to ridicule religion.

Eventually, Swift would look at his work and declare ‘Good God, what a genius I had when I wrote that book’. But that was late in life. In 1704 and again the following year, the Tale was controversial enough that a leading Anglican divine and philosopher, Dr. Samuel Clarke, argued against it in public. He did so in the prestigious Boyle lectures, then delivered in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

To have one’s first major book so prominently noticed might seem attractive to any aspiring author but for an ambitious clergyman to be considered by his eminent superiors to be a deist – a believer in a supreme being who remains remote from human affairs – or even an atheist was a very serious matter. Swift attempted to clarify his position in four subsequent editions published over the next five years, culminating in the fifth and final edition of 1710. Unfortunately for him, the changes he made were insufficient to gain him the ecclesiastical preferment he coveted. Queen Anne thought the author of A Tale of a Tub too unorthodox to receive preferment in England, with the result that Swift did not obtain the English bishopric he believed he deserved but famously became, instead, Dean of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

While Swift’s writings on religion reveal him to have been poised between the past and a future he foresaw more clearly than many of his contemporaries, his secular writings also suggest that Swift understood himself and his age to be at a significant moment in history: on the verge of what we think of today as Modernity. Taught to admire classical Latin poets such as Horace and Virgil, Swift was particularly alert to the ways such poets wrote of a world quite unlike that in which Swift and his contemporaries lived.

Between 1710 and 1714, Swift lived almost entirely in London. It was there, in the fashionable periodical, The Tatler, edited by Richard Steele and Joseph Addison that he published A Description of a City Shower, which offers a parody – a critical rethinking – of Virgilian georgic: poems about farming. In the countryside, rain brings refreshment and growth; in early-eighteenth century London it deluges Londoners with uncontrolled filth. After the shower, the city – still without a proper drainage or sewage system – sees its ordered world degenerate into chaos:

Now from all Parts the swelling Kennels flow,

And bear their Trophies with them as they go:

Filth of all Hues and Odours seem to tell

What Street they sail’d from, by their Sight and Smell.

They, as each Torrent drives, with rapid Force,

From Smithfield, or St. Pulchre’s shape their Course,

And in huge Confluent join at Snow-Hill Ridge,

Fall from the Conduit prone to Holborn-Bridge.

Sweepings from Butchers’ Stalls, Dung, Guts, and Blood,

Drown’d Puppies, stinking Sprats, all drench’d in Mud,

Dead Cats, and Turnip-Tops come tumbling down the Flood.

(ll. 53-63)

In these poems, Swift was not turning his back on his classical education but he was increasingly testing the authority of the past against modern lived experience.

This was true whether Swift was writing prose or verse. If he was under no illusion that he might follow his cousin Dryden as English Poet Laureate, Swift did harbour an ambition to follow him in the other great position that Dryden held: that of Historiographer Royal. One of Swift’s most ambitious works was his History of the Last Four Years of the Queen. It is also one of his least successful: unpublished during his lifetime, and read today only by Swift scholars and historians with a specialized interest in the final years of the reign of Queen Anne (even the title is not Swift’s own). If Swift could not succeed in such ambitious endeavours, then he was willing to turn his hand to more popular forms of publication.

So, many of the works by Swift that have the greatest appeal to readers today are what were, in Swift’s day, modern forms. Among these, the popular pamphlet is perhaps the most pervasive. Some pamphlets, like the Bickerstaff Papers – an elaborately cruel hoax whose ultimate aim was to defend the privileges of the Anglican Church – were immediately successful. Others might be as resistant to easy interpretation as A Tale of a Tub.

His Argument against Abolishing Christianity or, to give it its full title, An Argument to Prove that the Abolishing of Christianity in England May, as Things Now Stand Today, be Attended with Some Inconveniences, and Perhaps not Produce Those Many Good Effects Proposed Thereby is a short work whose complex, multi-layered irony begins with its title since – even in an increasingly sceptical age – no one had ever gone so far as to suggest abolishing Christianity.

During his years in Ireland after 1714, Swift further developed his skills as a pamphleteer. In 1720, he published A Proposal for the Universal Use of Irish Manufacture, which goes beyond what that title declares – an encourage to support the Irish economy by purchasing only Irish goods – to challenge the pretensions of the parliament in Westminster to legislate for Ireland, following the Declaratory Act of 1719.

The pamphlet had sufficient impact in Ireland that the Irish administration attempted to put the anonymous author on trial for seditious libel and when no one would identify the author – though many in Dublin knew it to be Swift – charged the printer, Edward Waters, instead. The result was a trial infamously presided over by Lord Chief Justice Whitshed, who sent out the jury – who returned a verdict of ‘not guilty’ – no fewer than nine times, to see whether they might arrive at a decision more acceptable to the judge and the administration at Dublin Castle.

Undoubtedly, the success of this pamphlet helped persuade Swift, somewhat belatedly, to join in the campaign against the patent granted to the English manufacturer, William Wood, to produce £108,000 worth of copper currency for a country badly in need of it. The supposedly poor quality of the coins was the occasion for Swift’s intervention in the guise of M. B. Drapier, in the pamphlets now known as the Drapier’s Letters. In these works, Swift is not addressing the intellectually curious reader for whom he had written A Tale of a Tub nor the politically influential readers he had hoped to find for The Last Four Years of the Queen. Instead, he wrote for a wide cross-section of Irish society and he made sure that the pamphlets he addressed to them were within the reach, even of the less educated, and least wealthy, among them. So the Drapier encourages his readers ‘to read this paper with the utmost attention, or get it read to you by others; which that you may do at the less expense, I have order the printer to sell it at the lowest rate’ – and in fact each pamphlet sold for just ¾ d.

It was in a similarly humble material form that Swift published A Modest Proposal: one of his most admired, and certainly the one that most clearly revealed the ‘savage indignation’ he attributed to himself in the Latin epitaph he wrote and which now adorns a tablet close to his grave in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World represents yet another form of modern literature. The expanding commercial empire of early-eighteenth century Britain and Ireland made knowledge of the world all the more important to readers, who showed a healthy appetite for travel writing of different kinds. Yet the many contemporary European voyages of discovery often made it hard for readers to know what to believe and what not to; the story of the Irish bishop who declared, according to Swift, that Gulliver’s Travels was ‘full of improbable lies, and for his part, he hardly believed a word of it’ may not be literally true but perhaps reflected the perplexity many readers felt in an age of discovery.

Swift’s challenge to his age was, however, far more radical than whether or not readers believed his story to be literally true. In a famous letter written on 29 September 1725 to his great friend, Alexander Pope, Swift described the work he was then engaged in writing (but had not yet completed): the work that would become Gulliver’s Travels:

I have got materials towards a treatise proving the falsity of that definition animal rationale [i.e. man is a rational being]; and to show it should only be rationis capax [that is, capable of reason].

Like other classically educated contemporaries, Pope would have recognized the true import of Swift’s words in a way that we find it harder to do today. For many hundreds of years, students had studied logic – one of the most important subjects in the curriculum. We even know the logic text-book Swift himself read: the Institutiones Logicæ written by the then-Provost of Trinity College Dublin, Narcissus Marsh, later Archbishop Marsh, and founder of Marsh’s Library in Dublin.

Among the propositions that Swift found in that book, two particularly stand out:

1. Homo est animal rationale [Man is a rational being]

2. Equus non est animal rationale [A Horse is not a rational being]

Any reader of Gulliver’s Travels will quickly recognize the possible relevance of these statements to an understanding Book IV of Swift’s masterpiece: ‘Voyage into the Country of the Houynhnms’, where the appalled Gulliver comes to perceive his own likeness in the bestial Yahoos, leading him to identify – often absurdly, as when he neighs when speaking, or trots when walking – with the rational horses, the Houynhnms.

Yet the exact nature of the view of humankind Swift is offering in Gulliver’s Travels and especially in its fourth book is something over which readers have argued since the book’s publication, variously finding it filthy, repulsive and shameful or, as a later the poet T. S. Eliot – himself an Anglican – memorably wrote: ‘one of the greatest triumphs that the human soul ever achieved’.

Here again, we see Swift looking both backwards and forwards: back to the classical world in whose values he was educated and forward even beyond his own time – an age once commonly known as the ‘Age of Reason’ – to a world that has lost faith in the reasonableness of the human race.

Swift lived at a time when many forms of received wisdom were coming under attack. In such early works as The Battle of the Books, he defends the wisdom and achievements of the classical past. As a Christian and, particularly, as a clergyman, he knew well the wisdom books of the Old Testament, including Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Book of Wisdom in the Apocrypha. Yet throughout much of his life, Swift the Modern recorded proverb-like aphorisms of his own devising: ‘Thoughts on Several Subjects, Moral and Diverting’, published in the first volume of Miscellanies (1711, 1727 and 1745).

So he wrote in a way that challenged contemporaries and perhaps challenges us more than ever today, in an age of easy access to information, via the internet and Google searches: ‘Some People will never learn any thing, for this reason, because they understand every thing too soon.’ He could also be very cynical: ‘I never knew any Man in my Life, who cou’d not bear anothers Misfortunes perfectly like a Christian.’

Like other of Swift’s ‘thoughts’ this is not entirely original; indeed this particular ‘thought’ is borrowed, and only slightly elaborated, by reference to Christianity, from one of the maxims of La Rochefoucauld: ‘We are strong enough to bear the misfortunes of others’.

And it was to the seventeenth-century French writer La Rochefoucauld that Swift looked in composing a poem that, in its own way, is also an unusually modern form. Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift offers, in a complex fashion, an autobiography (before that word had even been coined). The epigraph to the poem shows Swift at his most cynical, quoting in French a maxim of La Rochefoucauld’s: ‘Dans l’adversité de nos meilleurs amis nous trouvons toujours quelque chose, qui ne nous deplaist pas’ (‘In the adversity of our best friends we always find something that does not displease us’. The opening lines of the poem suggest the basic thrust of the argument:

As Rochefoucault his Maxims drew

From Nature, I believe ’em true:

They argue no corrupted Mind

In him; the Fault is in Mankind.This Maxim more than all the rest

Is thought too base for human Breast:

“In all Distresses of our Friends,

We first consult our private Ends;While Nature, kindly bent to ease us,

Points out some Circumstance to please us.”If this perhaps your patience move,

Let reason and experience prove.

(ll. 1-12)

The remainder of this extraordinary and entertaining poem purports to show exactly this: how both reason and experience suggest men and women are driven by ‘self-love’. Again, this was a debate with particularly modern resonance. Philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes, writing in the mid-seventeenth century, when Swift was born, argued that humans were indeed driven by ‘self-love’ or ‘self-interest’, prompting younger men, such as the Earl of Shaftesbury, Swift’s almost exact contemporary, to promote the more optimistic view that humans had an innate moral sense that allowed them to transcend selfishness.

So, Shaftesbury wrote:

Relations, Friends, Countrymen, Laws, Politick Constitutions, the Beauty of Order and Government, and the Interest of Society and Mankind … naturally raise a stronger Affection than any which was grounded upon the narrow bottom of mere SELF.

(Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times, 1.117 [1711])

Countering such optimism, Swift wittily takes contrary examples from everyday life:

Who wou’d not at a crowded Show

Stand high himself, keep others low?

I love my Friend as well as you

But would not have him stop my View.

Even allowing for the fact that Verses on the Death is a comic poem, Swift delights in presenting himself as a cynic. Yet selfless action – altruism – was no less a part of Swift’s character. In his ‘Thoughts on Several Subjects’ (1727), Swift proposed a view of Christianity as an incitement to civic and even political action: ‘To relieve the Oppress’d is the most glorious Act a Man is capable of; it is in some measure doing the business of God and Providence.’

Oppression, however, takes many forms. The conclusion of Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift contains some of the most characteristic lines Swift ever wrote:

He gave the little Wealth he had,

To build a House for Fools and Mad:

And shew’d by one satyric Touch,

No Nation wanted it so much.

In ‘Thoughts on Various Subjects’ in the 1727 Miscellanies, Swift had written of madness in a quite different way:

We ought in humanity no more to despise a Man for the misfortunes of the Mind, than for those of the Body, when they are such as he cannot help. Were this thoroughly consider’d, we should no more laugh at one for having his Brains crack’d, than for having his Head broke.

As is well known, Swift really did give the little wealth he had to build a house for ‘fools and mad’. The legacy he left allowed for the building of St. Patrick’s Hospital in Dublin which is still, though much enlarged, used today for the purpose for which Swift intended it – and Swift appears still more forward looking in suggesting that mental illness is not essentially different from – and certainly no more shameful than – physical illness.

During this week’s Dublin Swift Festival, Dubliners who have never read a word of Swift will have the opportunity to share in one activity that was also a feature of the academic conference held in Trinity College Dublin in June. They will be able to take the same tour of St. Patrick’s Hospital that was also offered to Swiftians from around the world under the guidance of the hospital’s current Medical Director, Professor Jim Lucey: a tour that allows visitors an opportunity to see for themselves Swift’s physical legacy.

Of course, here in the splendid Armagh Robinson Library we are reminded that, to celebrate Swift fully, we need not only to think of his place in popular consciousness but also to read his works – especially those less well known than Gulliver’s Travels or A Modest Proposal. In doing so, we shall find a wealth of amusement but we should also come to recognize that writing and reading do not exist as activities divorced from the world but – as Swift triumphantly showed – as incentives to changing it for the better.

________