The United Nations declared 2024 the International Year of Camelids (IYC 2024).

Camelids are key to the livelihoods of millions of households. Camelids contribute to food security, nutrition and economic growth as well as holding a strong cultural and social significance for communities across the world.

In this exhibition Camelids, Heroes of Deserts and Highlands we look at evidence of awareness of camelids in the Western world through printed sources available in the Library.

What are Camelids?

Camelids are herbivorous mammals with slender necks and long legs. There are two so-called tribes: the Camelini and the Lamini.

The Camelini tribe consists of:

- dromedary

- wild Bactrian camel

- Bactrian camel

and the Lamini tribe of:

- guacano

- llama

- vicuna

- alpaca.

Camelini can be found in Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and Australia.

Lamini can be found in South America.

Where do Camelids come from?

Camelids originated in North America around 50 to 40 million years ago.

Fossil evidence shows that about 17 million years ago the camelids developed separate strands, the Camelini and the Lamini.

Seven million years ago the Camelini migrated across the ancient land bridge between America and Asia.

The surviving members of this tribe can be recognised by distinguishable humps: one for the dromedary, two for the wild Bactrian camel and Bactrian camel.

Around three million years ago the Lamini migrated as well, but to South-America. The surviving members, the guacano, llama, vicuna and alpaca, did not develop humps.

What are camelids used for?

Members from both tribes have been domesticated, i.e. kept as farm animals, for millennia. They were, and in most cases still are, used to

- provide milk and meat.

- provide fibres for rope, tents, carpets (Camelini), wool for clothes (Lamini.) and leather.

- transport passengers and goods.

- support the military, in the camel cavalry.

Earliest Mention of Camels

One of the earliest mentions of camels in Western literature is by Greek historian Herodotus (5th century BC), the Father of History. He was so-called as he wrote the first narrative history in the Western World, The Histories.

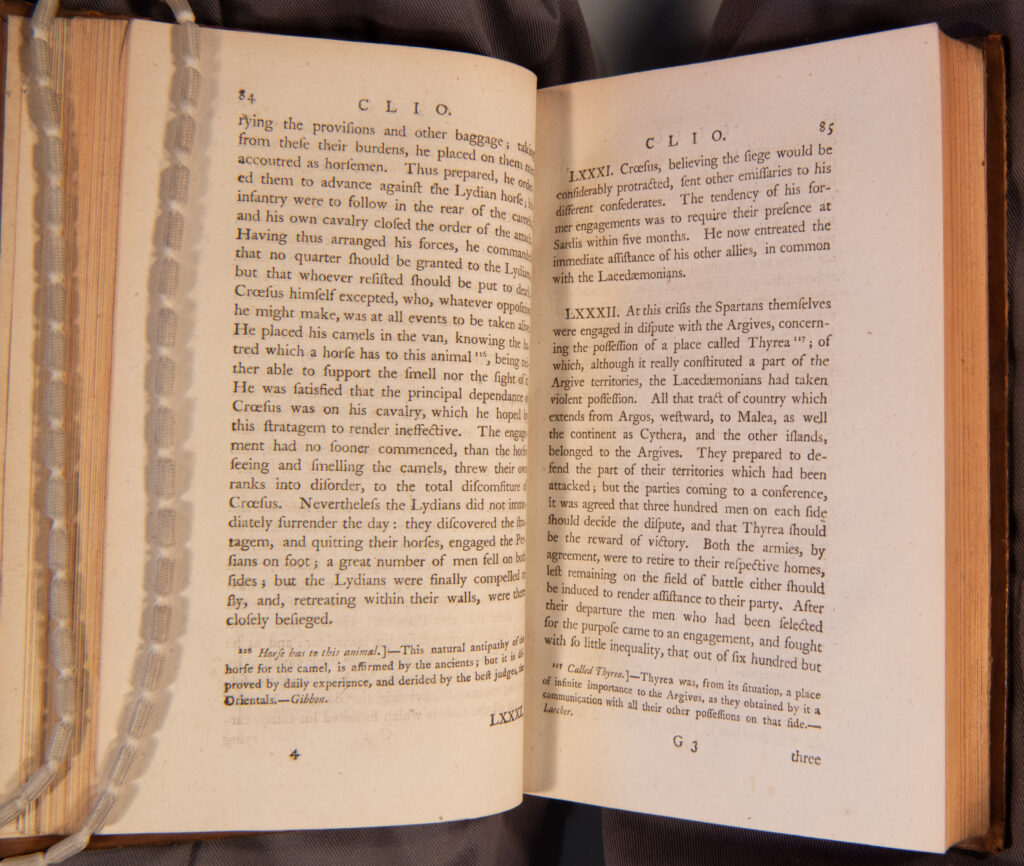

In The Histories he describes the battle between King Croesus and King Cyris around 547 BC

Croesus’ cavalry (military on horseback) heavily outnumbered Cyris’ cavalry. When Cyris heard that horses have a severe dislike of camels, he gathered all his pack camels into an impromptu camel cavalry, a camelry. The camelry created such chaos for the horses that Cyris won the battle.

The History of Herodotus, Translated from the Greek. With Notes. By the Reverend William Beloe. In Four Volumes ...

Herodotus

London, 1791

P001476595

Two humps, or one hump?

Philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC) was the first European to realise that dromedaries and camels were not the same animal.

In his Historia Animalium he distinguishes between the Bactrian camel and the Arabic camel, the first with two humps, the second with one hump.

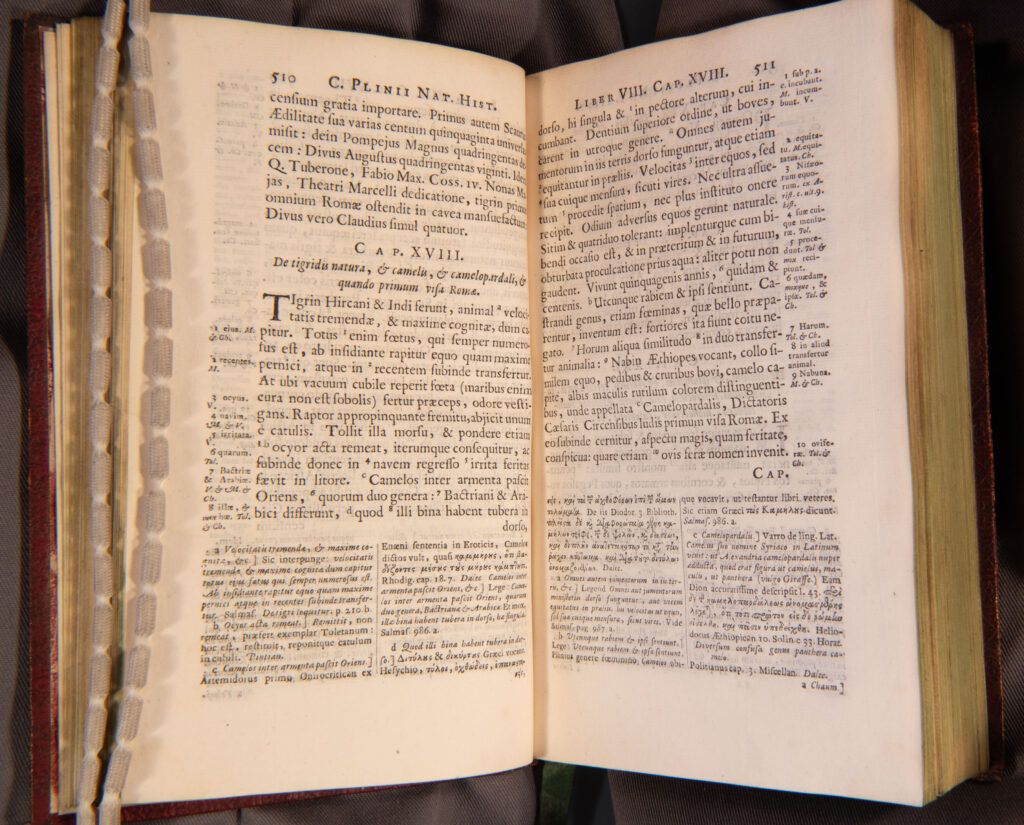

Naturalist Pliny (24-79 AD) repeats Aristotle’s finding in his Naturalis Historiae.

Translation:

Camels are found feeding in herds in the East. Of these there are two different kinds, those of Bactria and those of Arabia; the former kind having two humps on the back, and the latter only one; they have also another hump under the breast, by means of which they support themselves when reclining.

The Natural History, translated by John Bostock, 1906, Volume I, Cap. XVIII, bottom of page 510 – top of page 51.

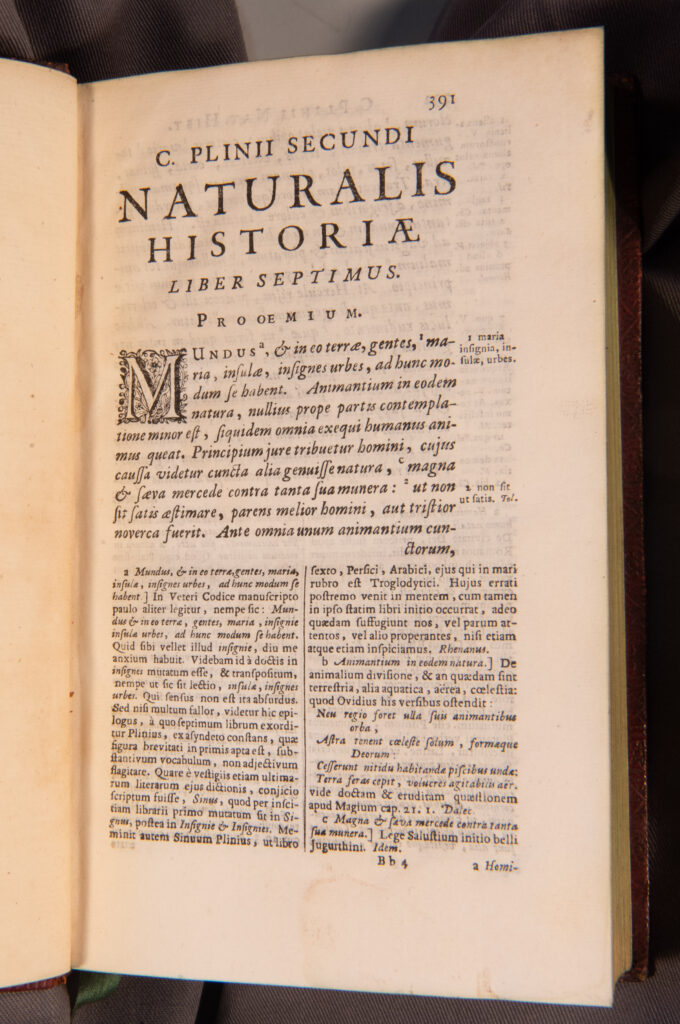

C. Plinii Secundi. Naturalis Historiae …

Pliny the Elder

Leiden, 1668-1669

P001111570

Camels in Medieval Europe

Archaeological and literary evidence shows that camels were used in Western Europe as pack animals for merchants, armies and travellers.

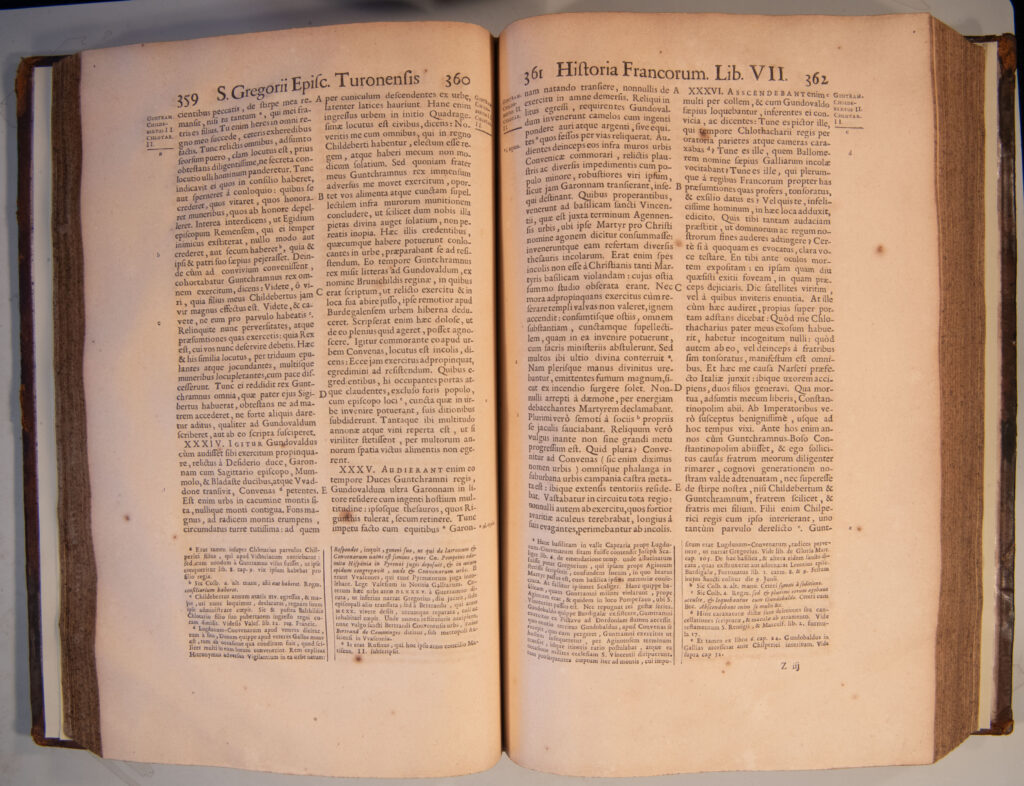

In his History of the Franks Bishop Gregory of Tours mentions the use of pack camels by Merovingian king Gundovald, in southern Gaul (modern France) in the 580s.

Translation:

The rest, on reaching the far bank, went in search of Gundovald, and found camels laden with a great weight of gold and silver, and exhausted horses which he had left behind along the roads.

History of the Franks. Lib. VII, Chapter XXXV, top column 361

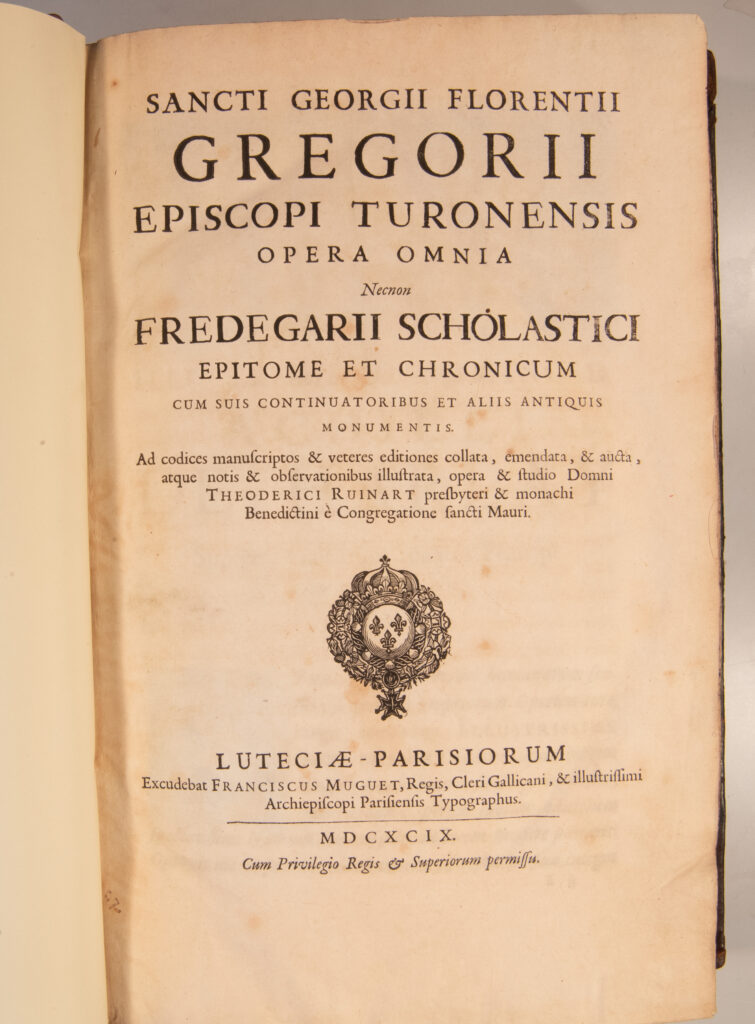

Sancti Georgii Florentii Gregorii, … Opera omnia, …

Gregory of Tours

Paris, 1699

P000998512

Royal Camels

From the twelfth century, leaders in Western Europe created menageries. These collections of wild and exotic animals for exhibition served as a symbol of power.

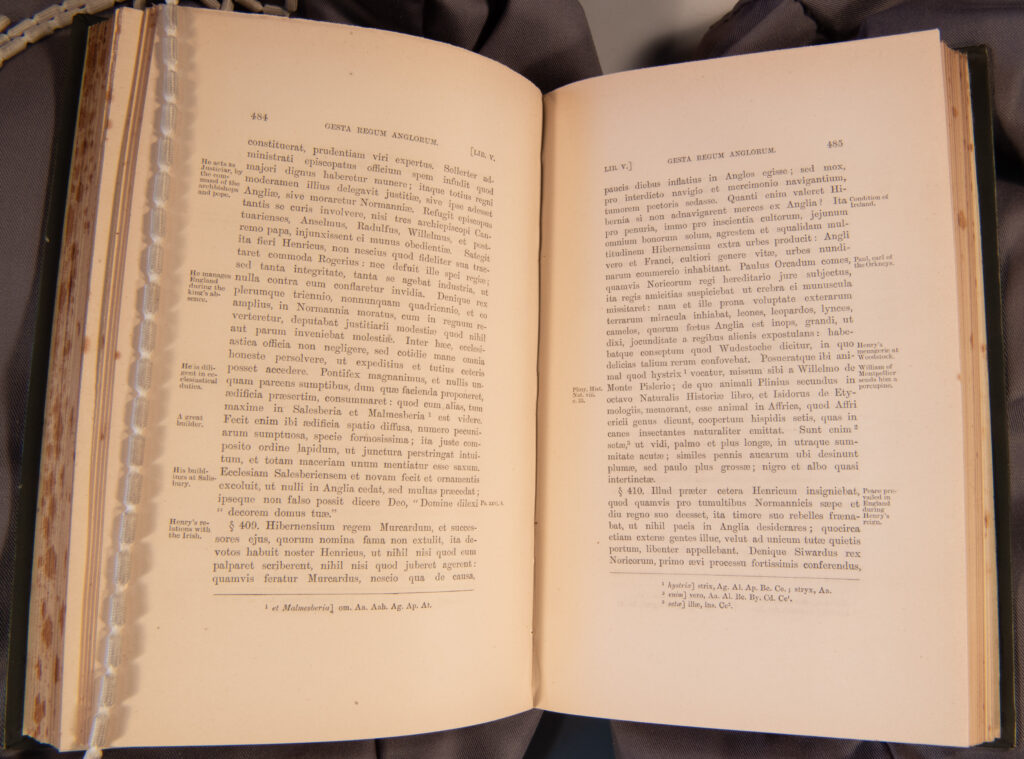

For example, King Henry I asked foreign kings to send him animals for his menagerie, including camels. (De Gestis Regum Anglorum, Volume II, Lib. V, §409, page 485)

This would suggest that, although camels were used as pack animals in Western Europe, they were not a common sight.

Translation:

For he was extremely fond of the wonders of distant countries begging with great delight, as I have observed, from foreign kings, lions, leopards, lynxes or camels, animals which England does not produce. He had a park called Woodstock, in which he used to foster his favourites of this kind.

William of Malmesbury’s Chronicle of the Kings of England …, J.A. Giles, 1847 (page 443)

In 1105 Henry I used a lion, a lynx, camels and an ostrich in a procession, after conquering the Normandy city of Caen.

Willelmi Malmesbiriensis Monachi De gestis Regum Anglorum. Libri Quinque; Historiae novellae, libri tres. William of Malmesbury 1887 (original from early 12th century) P001213217.2

Western Discovery of the Lamini

Before the 16th century, any descriptions and illustrations of camelids in Europe were only of Camelini, the Old-World camelids.

This changed when world exploration started at the end of the 15th century: scientists and artists started to bring back descriptions and art work of plants and animals from the New World.

The first description of a member of the Lamini was made during the European expedition to the East Coast of South-America (1519-1522).

It was described as a beast

As strange as that was that wore it; every way unaccountable, neither mule, horse or camel, but something of every one, the ears of the first, the tail of the second, and the shape and the body of the last.

The Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, Volume XXXVII, May 1767 Silvanus Urban London, 1767 P001204285

European naming of Lamini

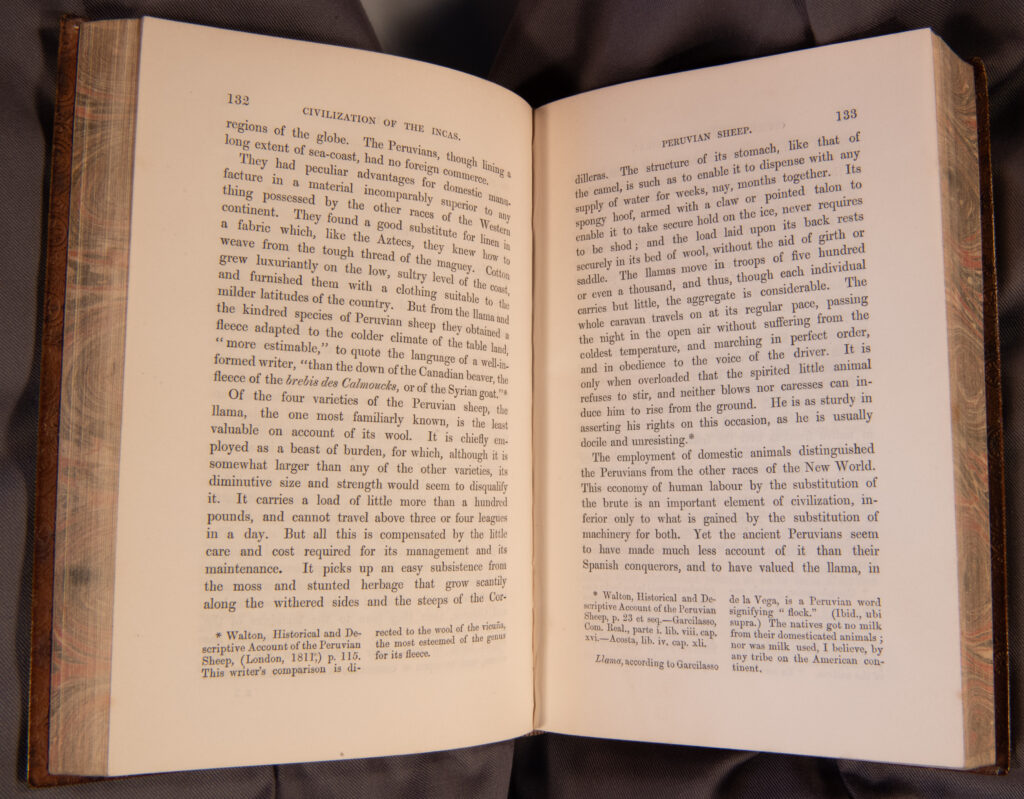

The Europeans would continue to call the Lamini ‘sheep’, ‘Peruvian sheep’ or ‘Indian sheep’ for more than two centuries, often ignoring the local names.

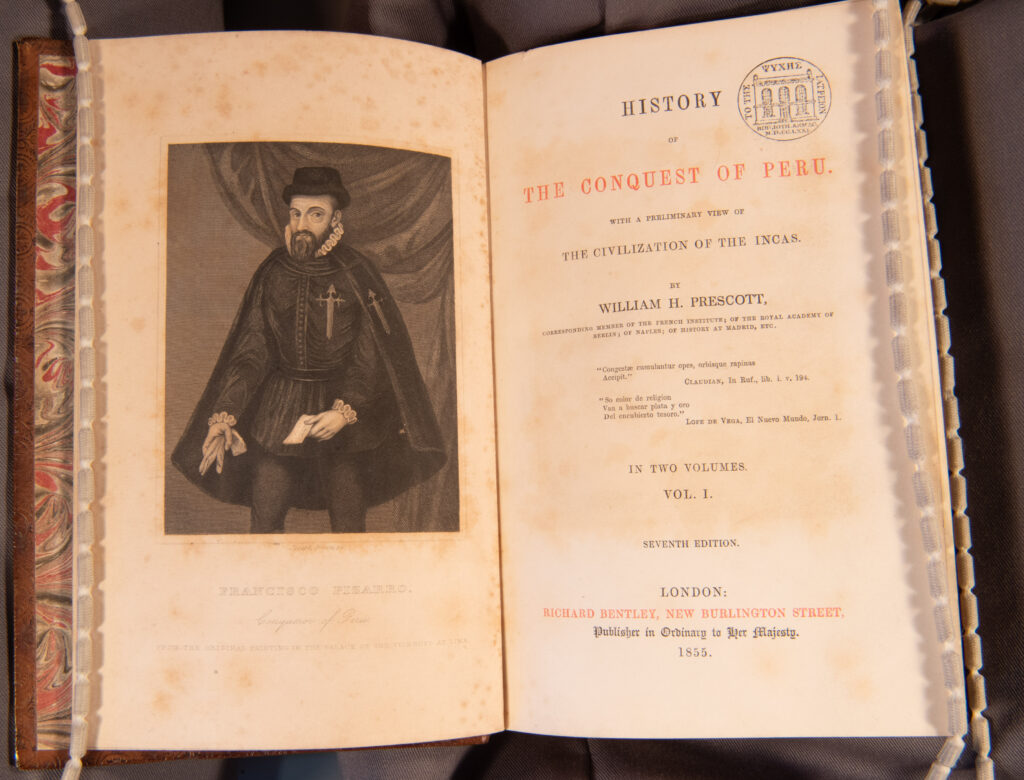

The 1855 History on the conquest of Peru mentions ‘the four varieties of the Peruvian Sheep’ as llama, alpacas, huanacos and vicunas.

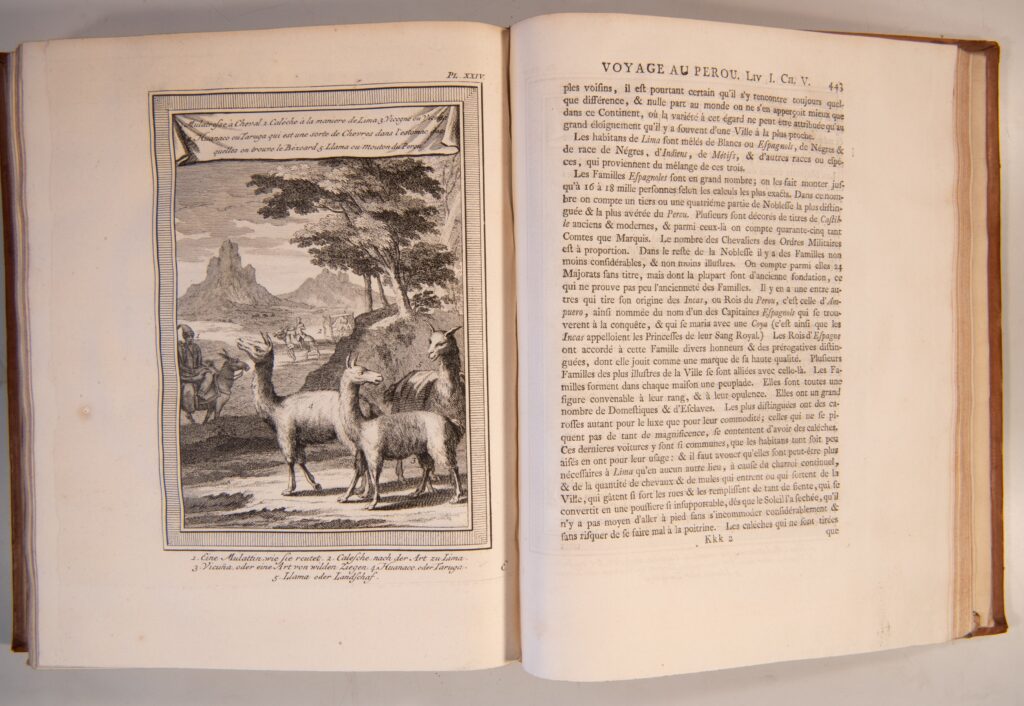

The mid-18th century report Voyage historique de l’Amerique Meridionale on political, astronomical, natural, and social observations in South America, includes a print of Lamini.

The caption still refers to the Lamini as ‘sheep’ or ‘goat’, although they now also list the local names.

The translation reads:

… 3. Vicuna, or a kind of wild goat, 4 Huanaco, or Taruga, 5. Llama, or land sheep …

History of the conquest of Peru with a preliminary view of the civilisation of the Incas. By William H. Prescott ... In Two Volumes ... Seventh edition Wiliam H. Prescott London, 1855 P001149071

Voyage historique de l'Amerique Meridionale fait par ordre du Roi d'Espagne par Don George Juan ... et par don Antoine de Ulloa … Antoine de Ulloa Amsterdam, 1752 P001147109

Taxonomy

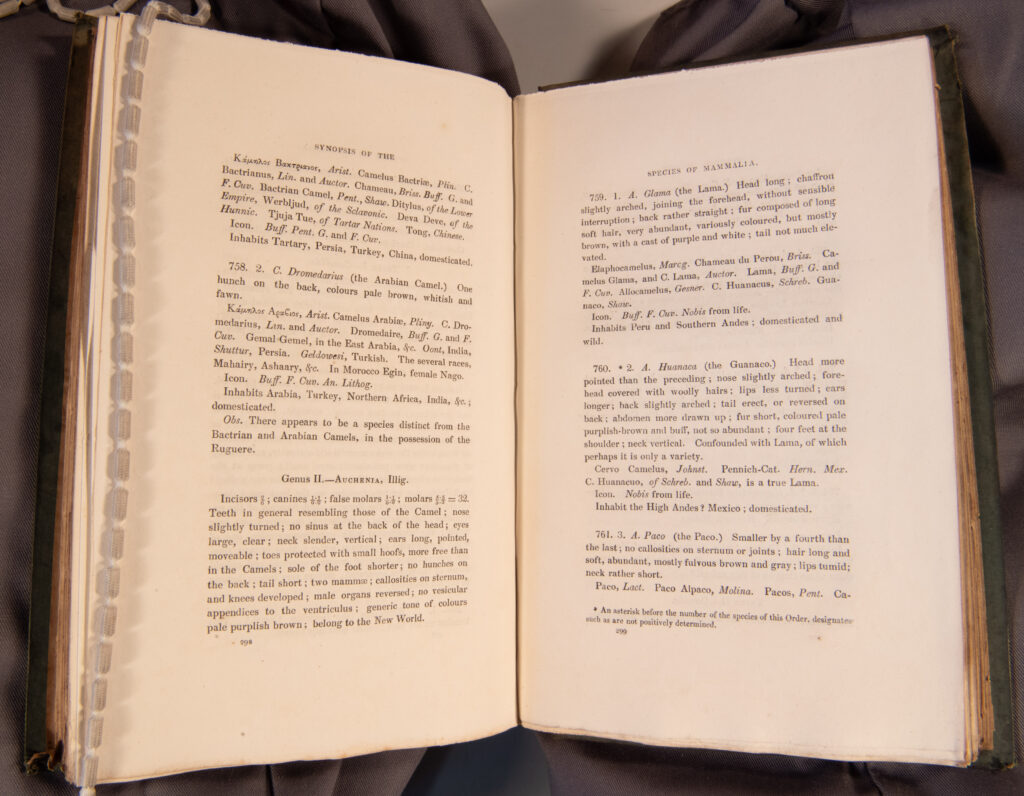

Although Europeans called the Lamini members ‘sheep’, they realised there was some similarity to camels.

When Carolus Linnaeus introduced a taxonomy (scientific classification) for living organisms in 1735, both llamas and alpacas were included in the genus Camulus.

In 1800 naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier moved the species llama, alpaca and guanaco to the genus Lama (which changed to Auchenia in 1811).

The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization George [M.] Cuvier London, 1832 P001318000

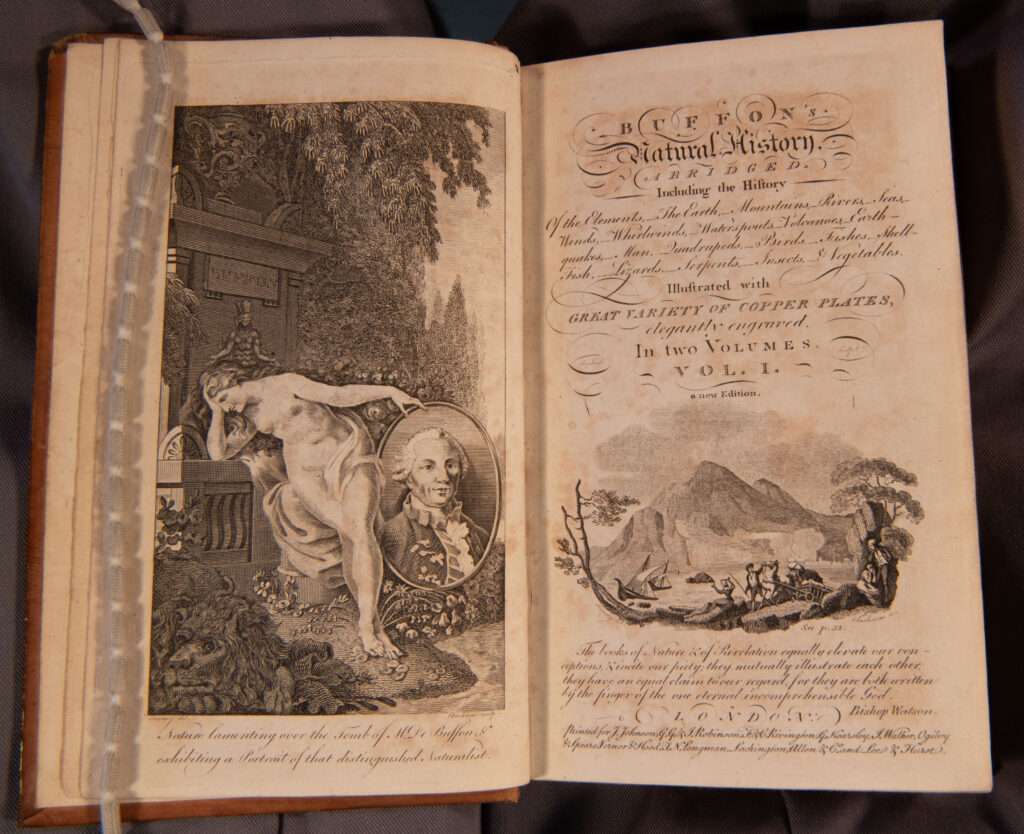

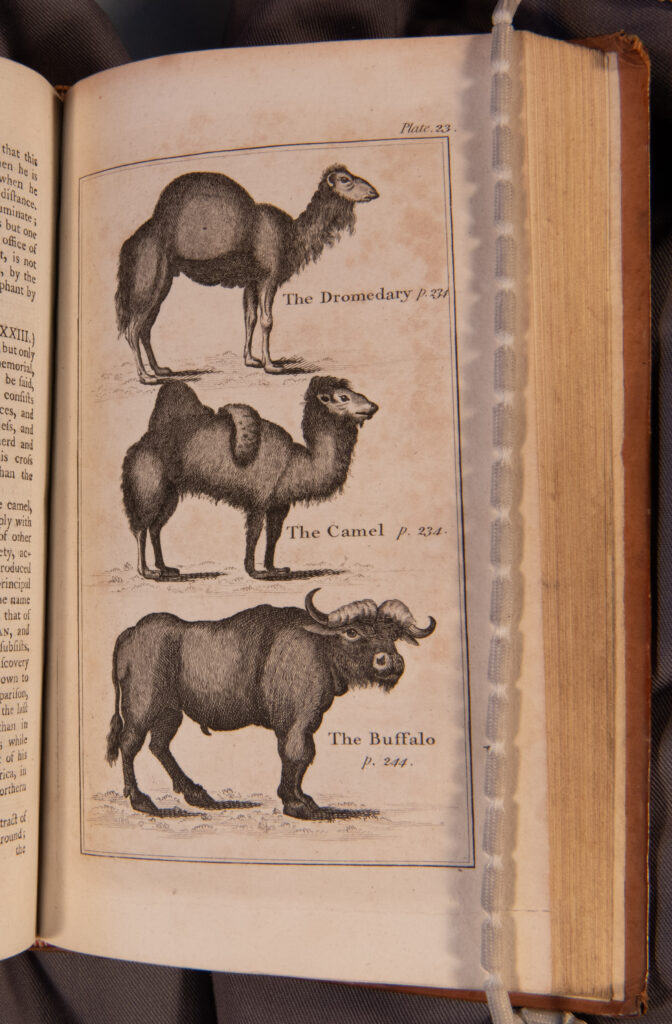

Buffon's Natural History, Abridged

Oliver Georges Louis Leclerc Buffon

London, 1792

P001146757

Evolutionary Biology

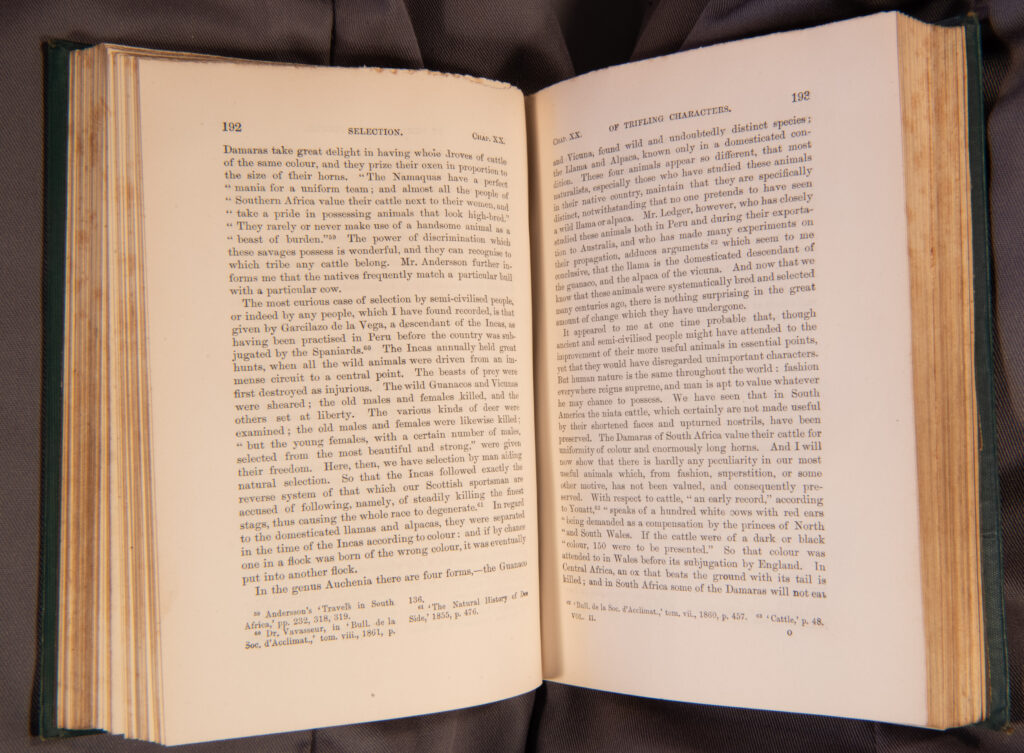

Darwin, naturalist and best known for his contributions on evolutionary biology, wrote about the different members of Lamini in The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication.

On page 192 and 193 he described the process of how the Incas would have selected wild guanacos and vicunas, and bred them to meet their own requirements.

Ultimately this led to the four distinctive members of the Lamini, two wild members and two domesticated.

The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. By Charles Darwin Charles Darwin London, 1888 P001094870