This exhibition shows a number of different decorative bookbinding styles from the late 15th century up to 1850s.

Books have been bound in various ways for centuries. The main reason of binding a book is to strengthen it and to protect the contents from damage.

However, a decorated book binding can also act as a mark of ownership, or attracts potential readers by creating decorated covers.

Over the centuries book bindings have been decorated in a variety of ways.

Decorating Tools

The most common way to decorate a binding is by tooling: pressing engraved tools into the surface of the covering material to create patterns.

The patterns made by these tools can be in gold (gold foil or leaf), in colour (coloured foil) or ‘blind’ (a dark impression caused by heat or an impression the same colour as the cover material caused by pressure alone).

Examples of decorating tools are:

- Fillet: a narrow wheel to create a straight or decorative line, or parallel lines.

- Roll: a patterned broad wheel to create a continuous repeat pattern.

- Gouge: a finishing tool with a metal curved edge to create a segment of a full circle.

- Palette: a long narrow tool to create continuous lines or narrow repeated designs.

- Lozenge: diamond-shaped tool.

- Handle letters: individual tools with letters and numbers to tool titles etc.

- Centrepiece: a finishing stamp, usually arabesque (intertwined lines and curves), stamped at the centre of the cover.

- Cornerpiece: a finishing tool, usually arabesque, used for the corners of a cover.

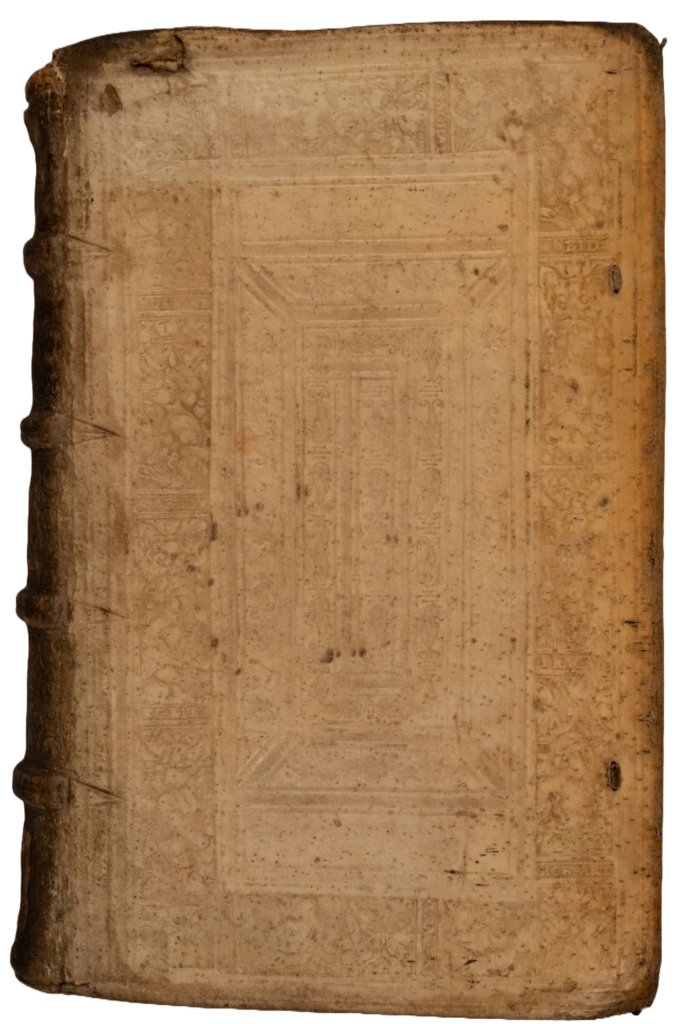

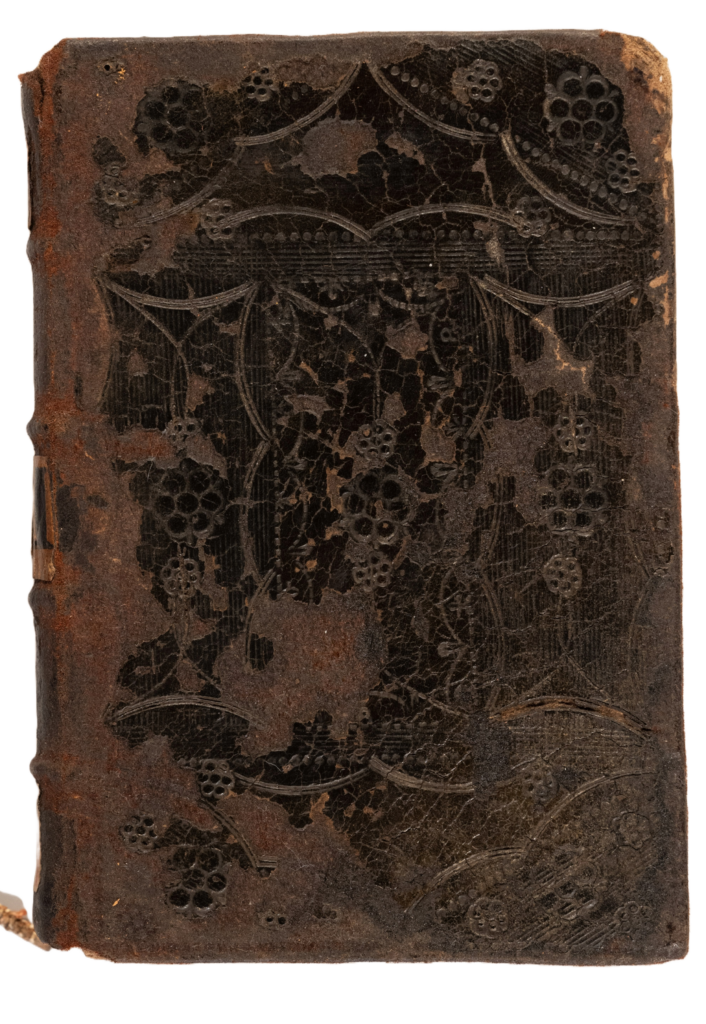

1 | Pigskin

In the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance pigskin was widely used for bookbinding in Germany and surrounding countries.

Pigskin leather was usually alum-tawed: soaked in alum and salt to cure it. This gave it a white colour.

It was one of the best materials to decorate, however, the colour could make it hard to see the pattern.

The binding below has an array of roll decorations, including an outer panel with personifications of Neid, Greitz, Traghät and Hoffart, German for four of the seven deadly sins: envy, greed, laziness and pride.

The second binding carries rolls with Christ on the Cross, the Brazen Serpent, and St John the Baptist, as well as individual tooled flowers and leaf patterns.

Dictionarum Medicum, vel, Expositiones Vacum Medicinalium, …

Henri Estienne, publisher

Geneva, 1564

P00112396x

Commentariorum In Vetera Imperatorum Romanarum Numismata

Enea Vico

Venice, 1562

P001394912

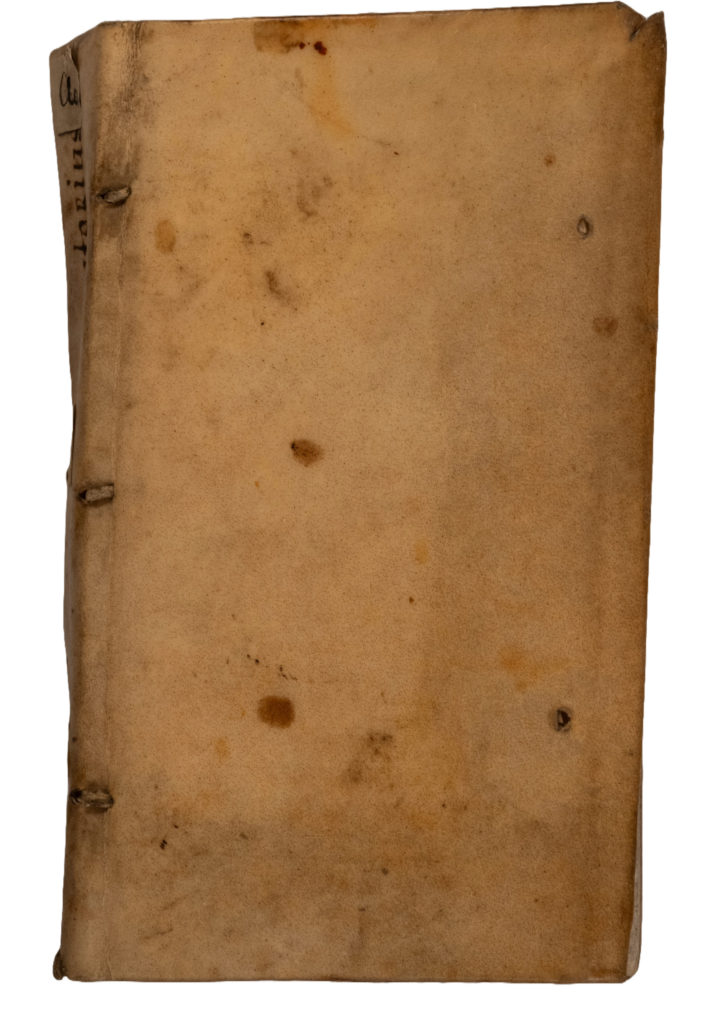

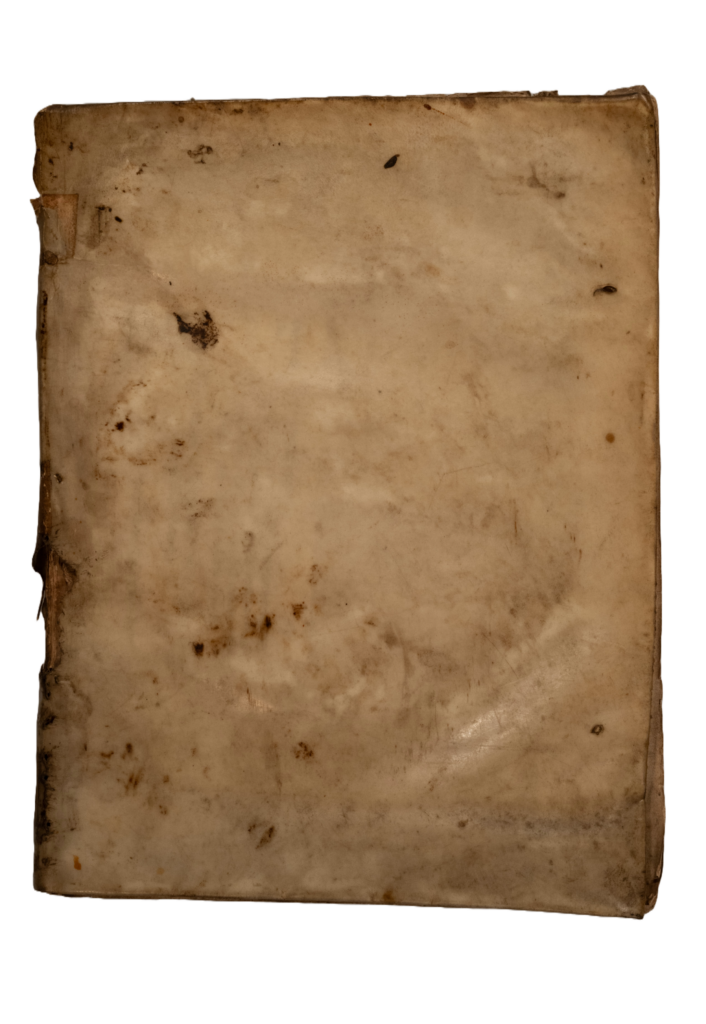

2 | Vellum

Parchment and vellum have also been used for bookbindings for centuries.

Skins for leather were tanned or tawed, skins for parchments (sheep and goat) and vellums (calf and cow) were stretched, de-haired and dried.

Parchment and vellum were often used as a cheaper alternative to leather.

Index expurgatorius librorum qui hoc saeculo prodierunt, vel doctrinae non sanem …

Johannes Pappus

[Strasbourg (France)], 1599

P001338591

Antidotum continens pressiorem declarationem propriæ et geniunæ sententiæ..

Synodical Typographic Office

Harderwijk, 1620

P000987359

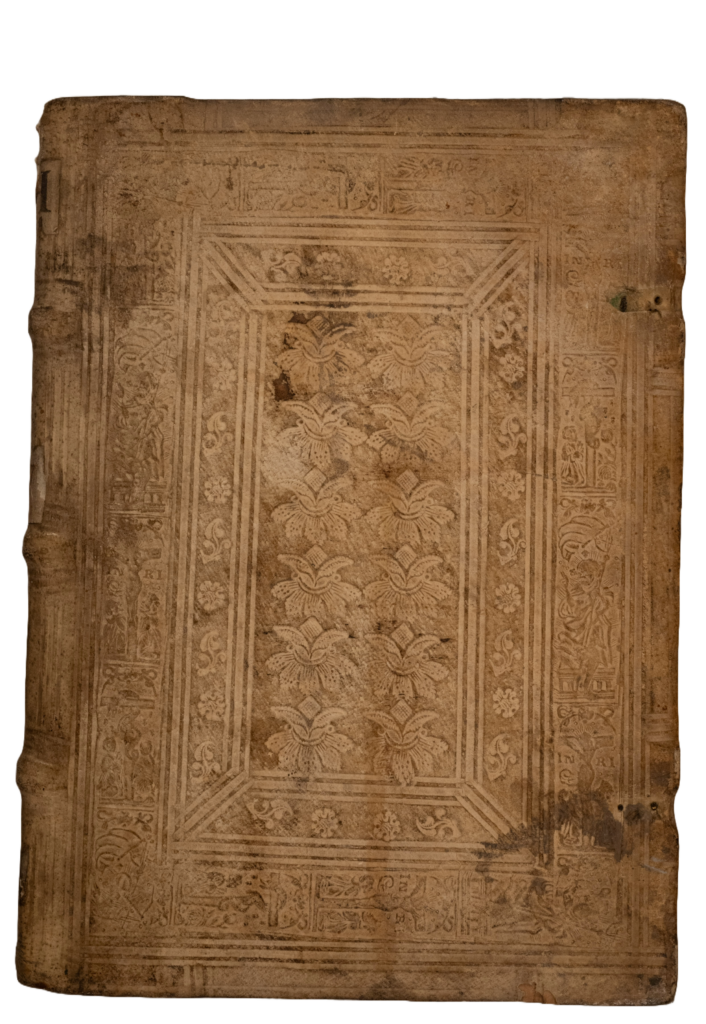

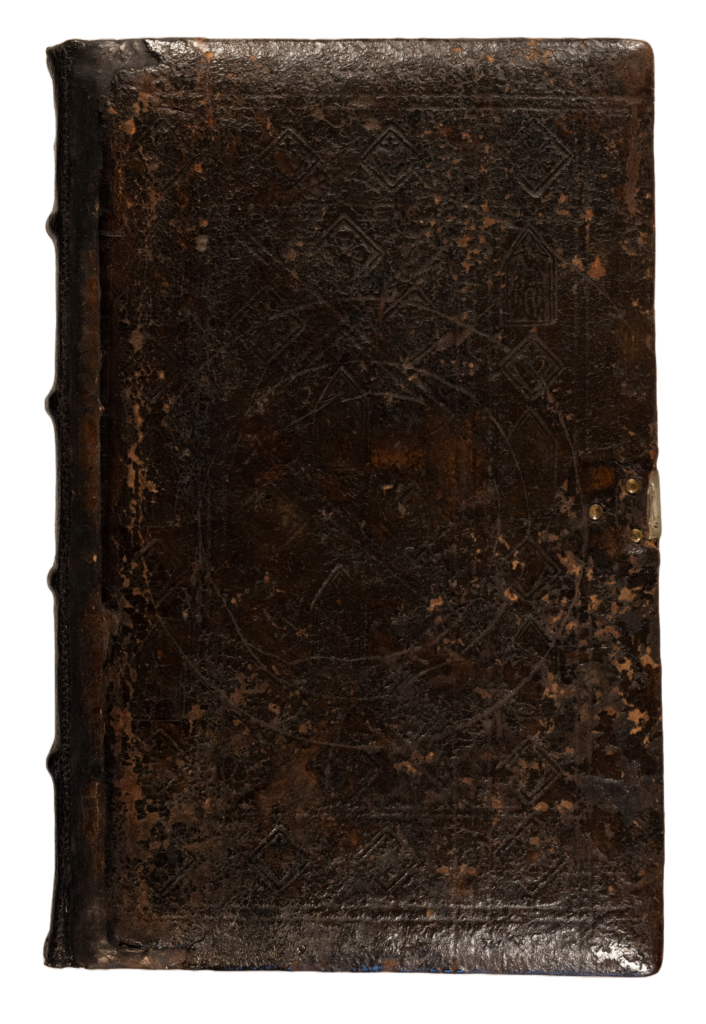

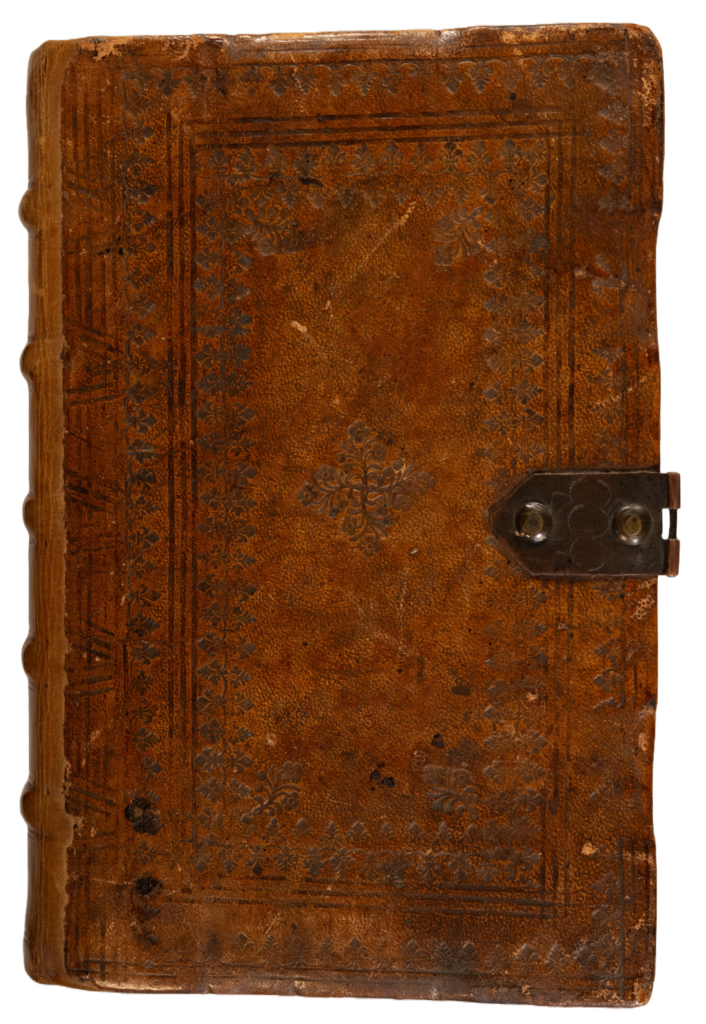

3 | Diaper Bindings

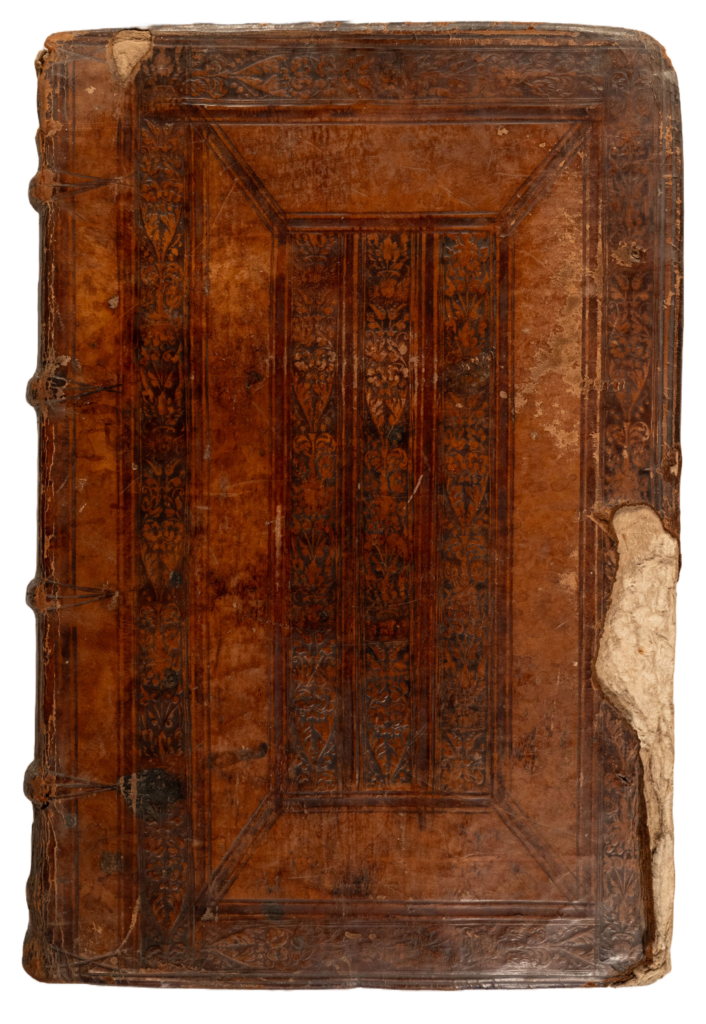

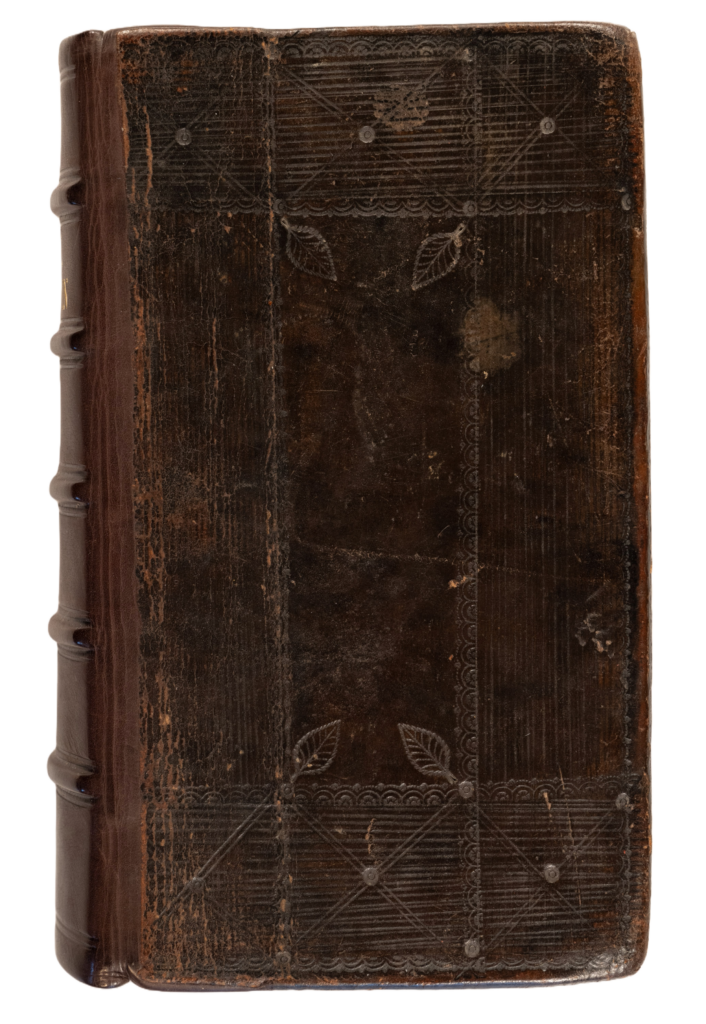

4 | Broad Rolls

From around 1470 diaper bindings became popular: a binding with a geometric pattern of constantly repeated shapes blind tooled into the leather.

The phrase Diaper refers to diaper damask: a woven, reversible fabric with small geometrical patterns such as bird’s eye or diamond shapes.

The book binding pattern could consist of diamonds, lozenges, or flowers, or of repeated compartments, each filled with particular designs.

From around 1500, broad rolls began to be used, rather than individual tools, to create patterns. This made the work a lot easier and quicker.

The rolls were used to create the older diaper patterns, but also for newer vertical panels.

The binding below is decorated with a motif known as “mother and child”. The motif is repeated in gothic window compartments.

The binding below shows the broad rolls being used for both the border and the central vertical panel.

The darker areas, where the hot metal was pressed into the leather, clearly show up black against the lighter colour of the leather.

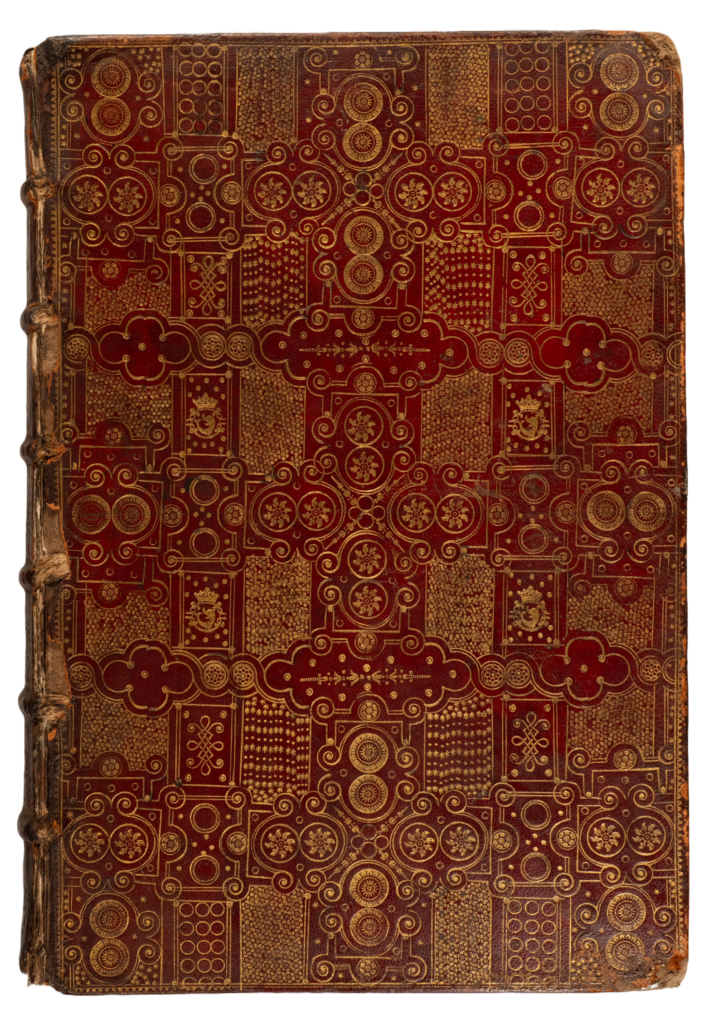

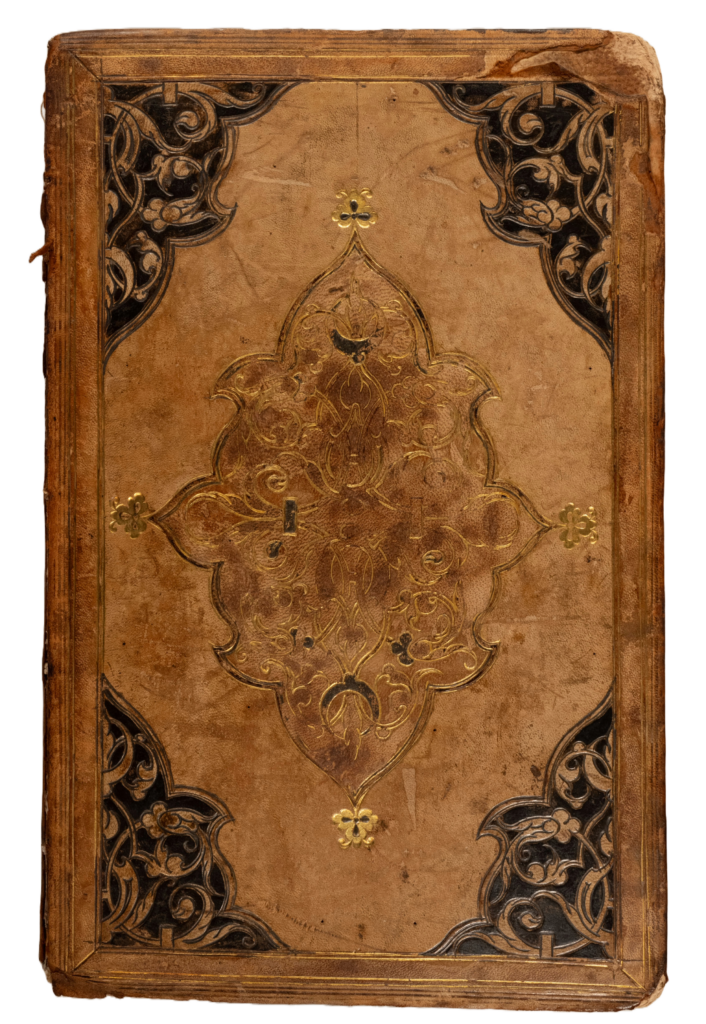

5 | Gold Tooling

6 | Simple Geometric Pattern

Examples of blind tooling can be dated as far back as the 700s.

The earliest examples of gold tooling, dating back to the 14th century, came from countries such as Syria, Persia and Egypt.Gold tooling spread to Europe in the late 15th century, through the city of Venice. At the time Venice was the wealthiest city in Europe, the gateway for trade between East and West, as well as the world’s printing capital.

As a result, the bookbinding trade was booming, and gold tooling became very popular with Venetian bookbinders.

Mid-16th-century bindings often used arabesque-style tools in simple geometric patterns.

The binding below is a beautiful example of such a Venetian binding with repeated gold tooled geometrical patterns.

The patterns include an armorial with a dolphin, which might indicate the book came from the library of a prominent noble family in Venice, the Delfin, or Delfinos.

The binding below has two blind tooled panels with gold tooled arabesque decorations in the four corners and in the centre.

I Quattro Libri del l’Architettura

Gerolamo Andrea Palladio

Venice, 1570

P001393207

Hieronymi Cardani, Mediolanensis medici, De utilitate ex aduersis capienda libri IIII. …

Gerolamo Cardano

Basel, 1561

P00135533x

7 | Strapwork

This binding is an example of a Lyonese, or strapwork binding, a 16th-century bookbinding style.

Although the name suggests otherwise, the style had any connection with the city of Lyon.

The binding was covered with interlaced strapwork, or ribbon-like decorations. It was usually gold tooled and then painted, lacquered, or enamelled in various colours.

Like the example below, strapwork often features large corner pieces and a lozenge shaped centrepiece, as in this example.

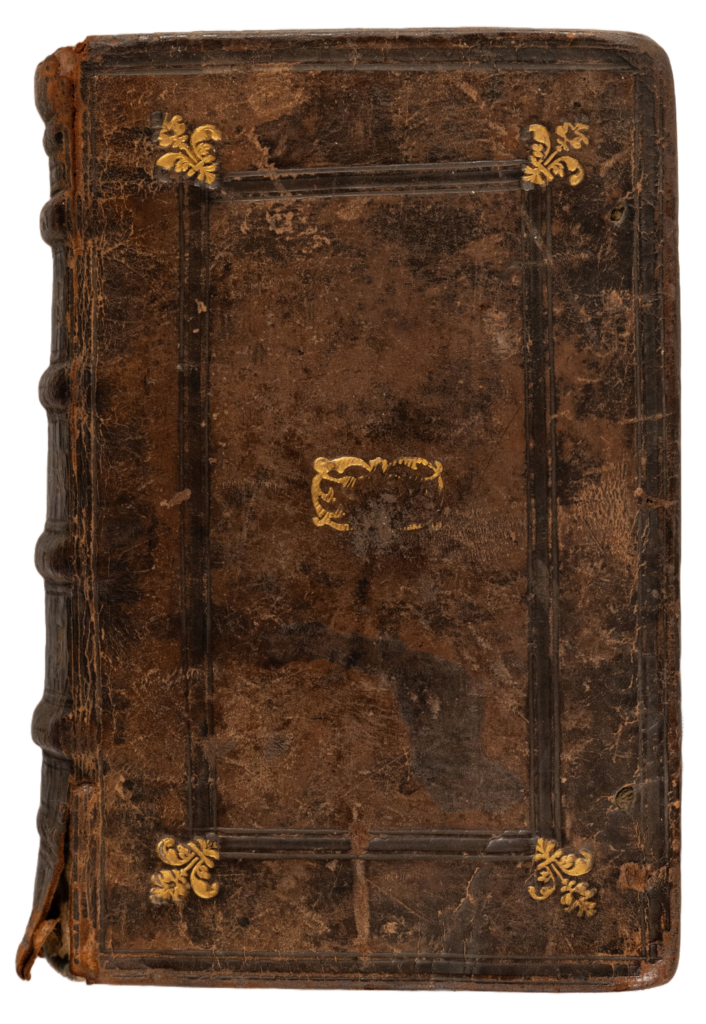

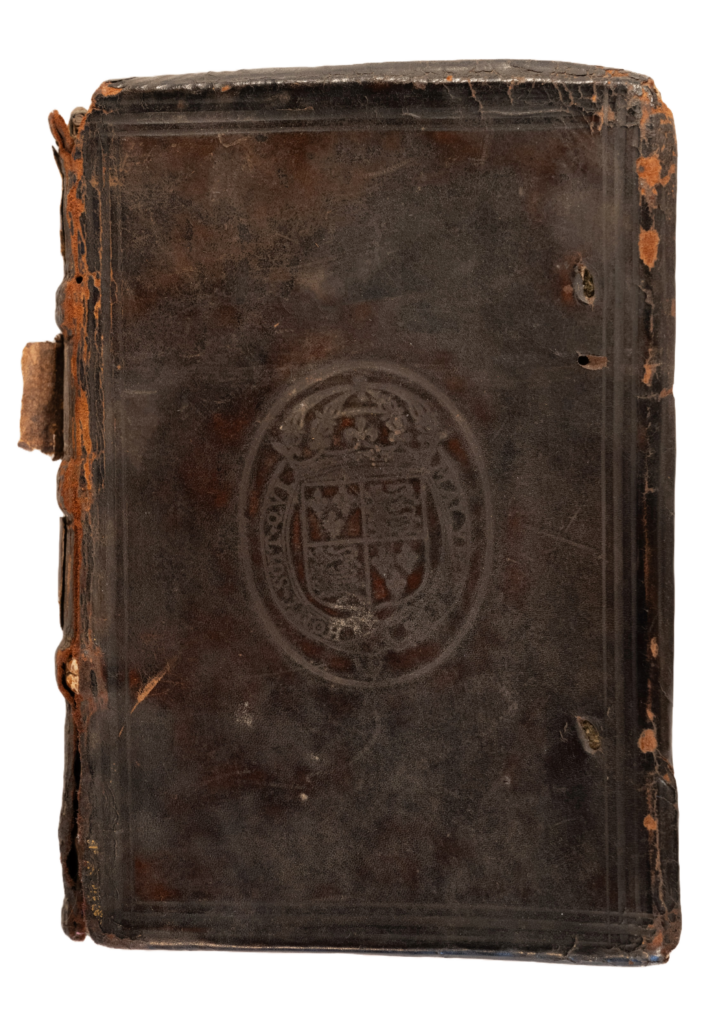

8.1 | Centrepieces

Centrepiece bindings were tooled with a single symmetrical design, like an armorial stamp, or a more elaborate central design, with matching corner pieces.

They were very popular in the latter half of the 16th century through to the beginning of the 17th century.

The binding below carries the armorial stamp of Queen Elizabeth I. The armorial consists of:

- the Sovereign crown at the top;

- the order of the garter surrounding the arms;

- the arms quartered with the three fleur-de-lis top left and bottom right, representing France, and three lions passant (walking) top right and bottom left, representing England.

The second armorial binding carries the armorial stamp of Viscount Edward Conway (1594-1655).

Conway was one of the most important book collectors in 17th-century Britain and Ireland. His library at Lisnagarvey (Lisburn) had some 8,000 volumes.

Many of these are believed to have been destroyed during the 1641 Rising. Some sixty volumes however survived and are now part of Armagh Robinson Library, along with a handwritten catalogue of Conway’s Irish library.

9 | Narrow Rolls

10 | Blind Lines

In the 16th-century rolls were quite wide, but in the early 17th-century rolls became narrower and more detailed in design.

Simple standard bindings were often decorated with blind lines only from 1600 to about 1640.

The binding on display has been blind tooled with triple fillet border, a triple fillet panel, narrow crested rolls and a small centrepiece.

The crested roll contains, amongst others, the fleur-de-lis.

Like the book on display, the blind lines run along the edges.

Biblia Sacra Vulgatae editionis, Sixti Quinti Pont. Max. iussu recognita atque edita.

Johannes Mortus, printer

Antwerp, 1599

P001615366

Chalcidii v. c. Timæus de Platonis translatus : item ejusdem in eundem commentaries ..

Calcidius

Leiden, 1617

P001458759

11 | Blind Lines Plus Spine Line

12 | Frames

In the 1640s the single-frame blind lines design for simpler bindings was replaced with a design of an additional vertical line near the spine.

These bindings were particularly popular from the 1640s to 1680s, but continued to be made into the 18th century.

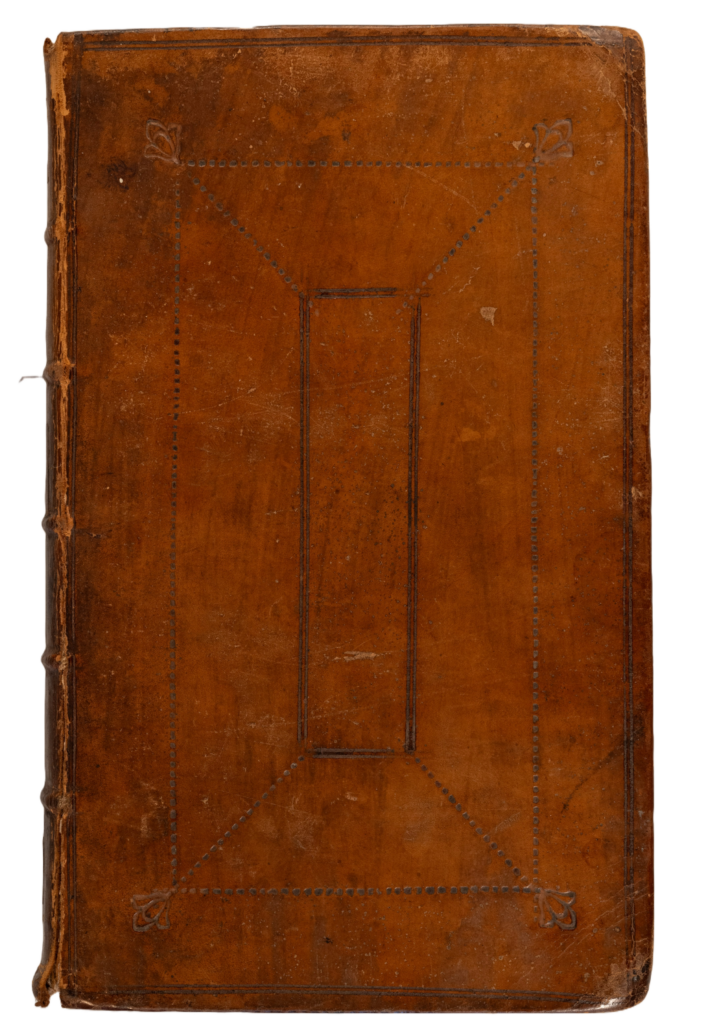

From 1660 onwards, book bindings with two or more concentric frames were made more and more often, with different levels of decorations.

Some consisted of just the frames with some corner pieces.

Others had the spaces between two frames completely filled with mottling, speckling or other decorations.

The binding on display clearly shows a double filet border and a triple spine line. The leather show signs of damage, where the stretching of the leather during preparation, caused small holes. The grain of the leather, tiny darker spots, is also clearly visible.

The binding below consists of just the frames with some corner pieces.

Exercitationes aliquot metaphysicæ, de Deo …

Roger Twysden

Oxford, 1658

P000981512

De Legibus Naturae Disquisitio Philisophica, In Qua Earum Forma Summa Capita, Ordo, Promulgatio, & Obligatio è Rerum Natura Investigantur…

Richard Cumberland

Dublin, 1720

P001346640

13 | Sombre Binding

Sombre bindings were popular between 1670 and 1720. Its name reflects the character of the binding: black leather, blind tooling and black edges.

Most sombre book bindings contained religious works, and were made specifically for use while people were in mourning, or during the season of Lent.

The bindings were often decorated with parallel lines, squares, cottage-roof design (a rectangular panel with a slanted top and base), flowers and pyramids.

Both sombre bindings below show the black leather and edges.

The book on the left shows a cottage roof design, hatched lines (lines drawn closely together) and flowers.

The book on the right shows hatched lines, squares and leaf designs.

He Kainhe Diathekhe apanta. Novum Testamentum. …

Robert Estienne, printer

Paris, 1549

P001336564

Biblia Sacra sive Testamentum vet. ab Im: Tremellio & Fr. Junio ex Hebræo Latine redditum et Testamentu novu a Theod: Beza è Græco in Latinu vers

Theodore Beza, translator

London, 1661

P000981660

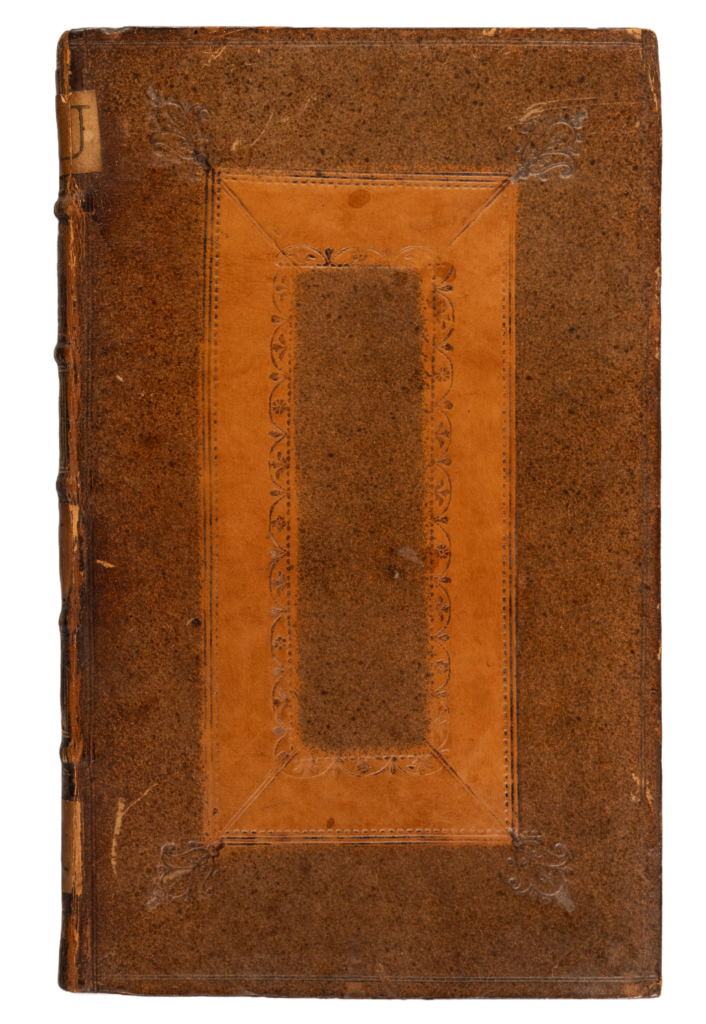

14 | Cambridge Panel

15 | Harleian

The Cambridge panel was the most popular design for basic bindings in the first half of the 18th century.

The binding was decorated with three rectangular frames in double blind lines. The spaces in-between the frames were sprinkled or stained.

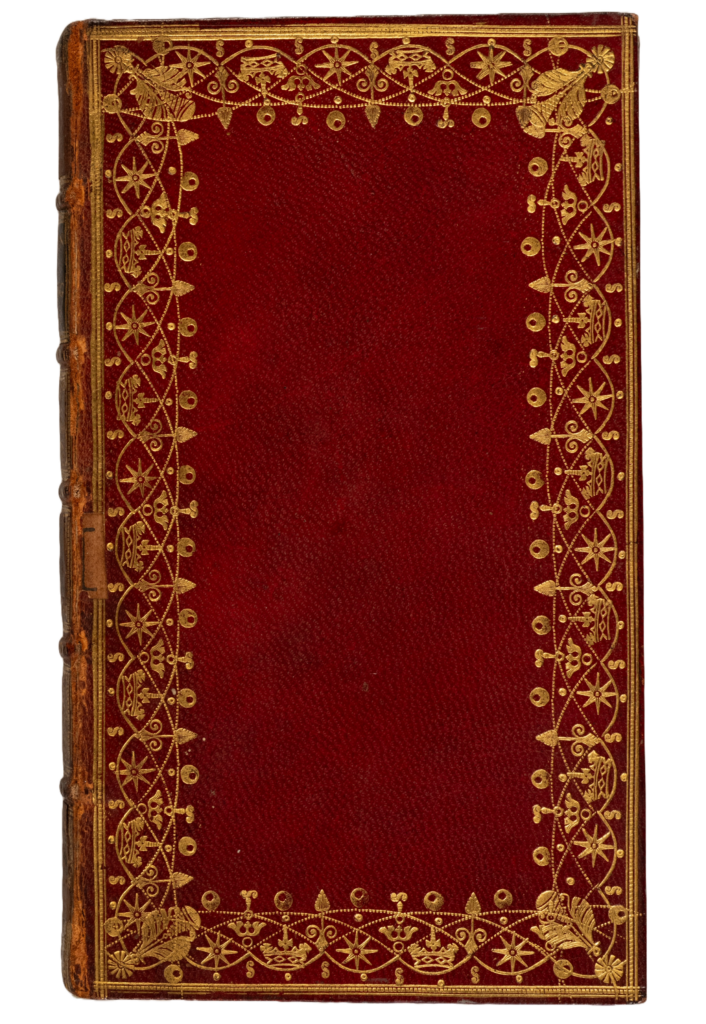

The Harleian binding was originally used for bindings in the library of Robert Harley (1661-1724), and his son, Edward (1689-1741).

An original Harleian binding was made of red goatskin. The “full” version had a lozenge centrepiece with a rolled border around the edges.

A simpler Harleian style had either a border or a lozenge, but not both.

The binding on display is a nice example of a sprinkled outer and inner frame, along with blind tooled corner pieces and inner panel border.

The binding below is an example of a full Harleian-style binding, with gold-tooling on the boards, board edges and turn-ins.

The clergy’s right of maintenance. Vindicated from scripture and reason. By William Webster, M.A. Curate of St. Dunstan’s in the West

William Webster

London, 1726

P001426539

Boulter’s monument. A panegyrical poem, sacred to the memory of that great and excellent prelate and patriot, the Most Reverend Dr. Hugh Boulter; Late Lord Archbishop of Ardmagh, and Primate of all Ireland

Samuel Madden

London, 1745

P001413437

16 | Irish Bindings

Irish binders from the 18th century were often referred to by a nickname, or by the publisher they bound books for.

The earliest binders for Trinity College Dublin were famous for Harleian style bindings, the so-called Irish Harleian.

16.1 | George Faulkner’s Binder

The binder working for George Faulkner, formerly known as the Rawdon binder, was one of the largest binders in Dublin in the middle of the 18th century.

The binder is said to have bound many books for Sir John Rawdon (1720–93), 1st Earl of Moira, one of the most important book collectors in Dublin at the time.

One of the most characteristic tools George Faulkner’s binder used, is visible in the centre of each side: a crossed ribbon within a shield.

This is found on many of his bindings, along with some of the other tools.

16.2 | Boulter Grierson’s Binder

16.3 | Anne Leathley’s Binder

Boulter Grierson was a Dublin printer and publisher in the second half of the 18th century, taking over from his father George Grierson in 1756.

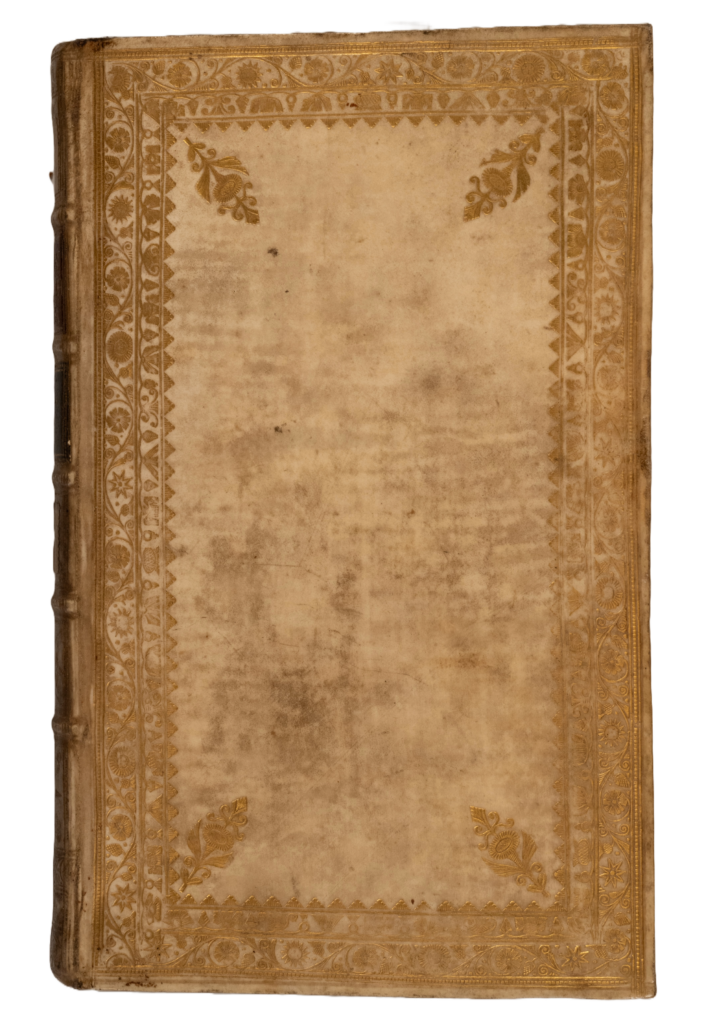

The majority of Trinity College Dublin’s goatskin bindings were produced by the binder who worked for Joseph Leathley (publisher from 1719 to 1757).

After Joseph’s death, his wife Anne took over the business, and employed a different binder, who worked with both goatskin and vellum.

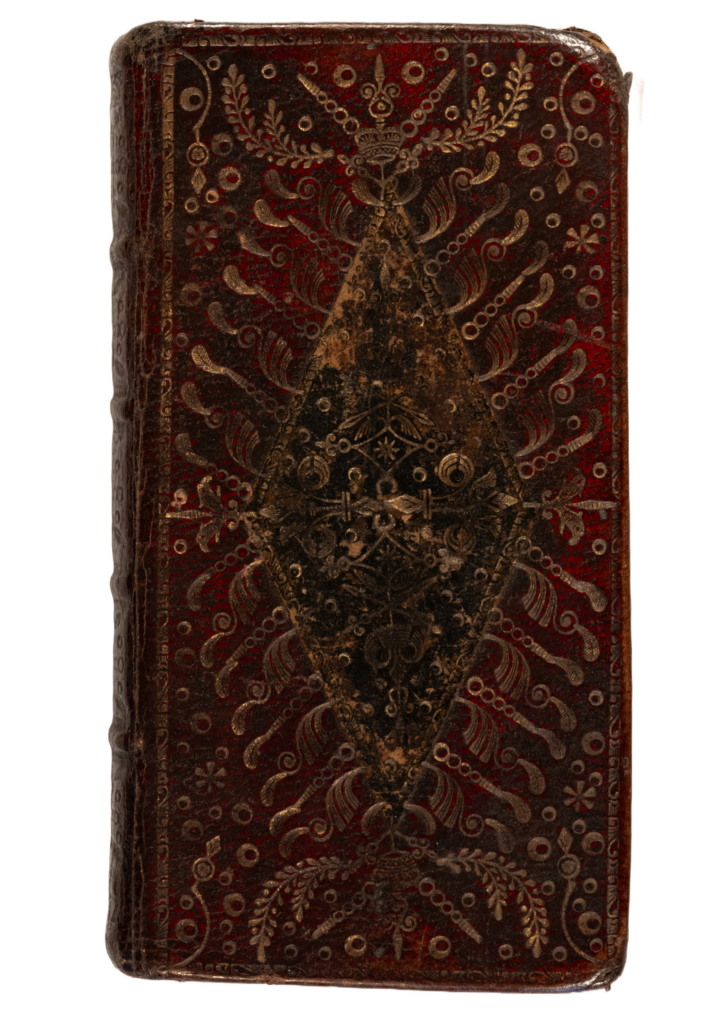

The little binding below is one of the smallest books in the collection. It is bound in red leather with black staining and gold tooling. The all-over style tooling is characteristic for the period. It includes feather tooling, crowns, stars, moons, branches.

As the book was printed by Boulter Grierson and the style is contemporary, it is very likely that ‘Boulter Grierson’s binder’ was responsible for this little binding.

The binding on display is an example of a Dublin vellum binding. The white vellum has been gold tooled and the book block has green and red splashed edges.

The tool of the flower in each corner is linked to the Anne Leathley’s binder.

17 | Leather Clad

18.1 | Quarter and Half Leather

In the 18th century many books in the cheaper end of the market were bound in basic leather bindings, without any decoration.

From the 1730s onwards, the cost of having books fully bound in leather increased significantly.

As a result, many books were bound with paper boards, and only parts in leather.

Parrhasiana, ou, Pensées diverses sur des matiéres de critique, d’histoire, de morale et de politique : avec la défense de divers ouvrages de Mr. L.C.

Theodore Parrhase

Amsterdam, 1701

P001209449

Letters on the Study and Use of History …

Henry John

London, 1752

P001458600

18.2 Half binding

19 | Full Paper Cover

Paper-only bindings, with paper covering thin boards were introduced around 1750 and became common after 1770.

This method of covering hard cover books was the cheapest available option.

Half leather bindings had leather covered spines and corners, like the volume on the right.

The binding below is covered with the blue-grey paper typical of the time.

20 | Calf

Calf leather bindings had a very smooth surface and were usually light brown. However, they were easily dyed.

20.1 | Tree Calf

20.2 | Mottled Leather

One example of a dyed binding was the tree calf binding. This type of binding was made by staining the boards in a particular way, so that a tree-shaped pattern appeared.

The earliest tree calf binding known was made in 1775.

Mottling and speckling were other uses of stain to decorate calf leather covers.

For mottling the stain was applied with a cloth, brush, or fingertip. For speckling, the acid was sprinkled or splattered.

Mottling became very popular in the second half of the 18th century.

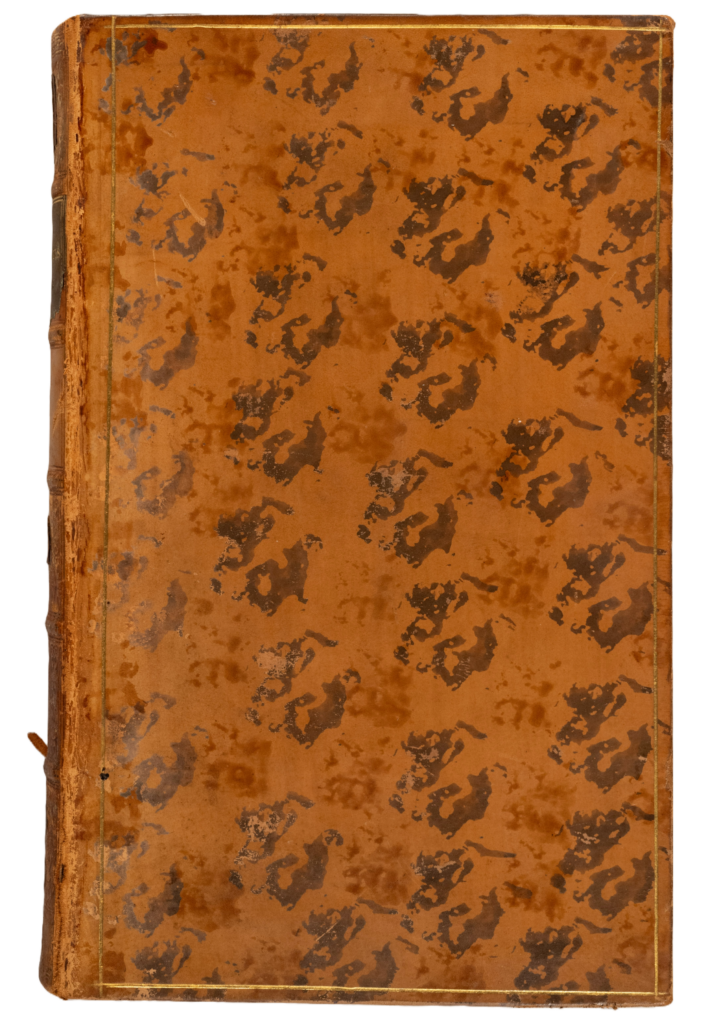

The mottling decoration on the binding below is called ‘cat’s paw’, as it looks as if a cat walked across the cover with ink covered paws!

20.2 | Mottled Leather

20.3 | Reversed Calf

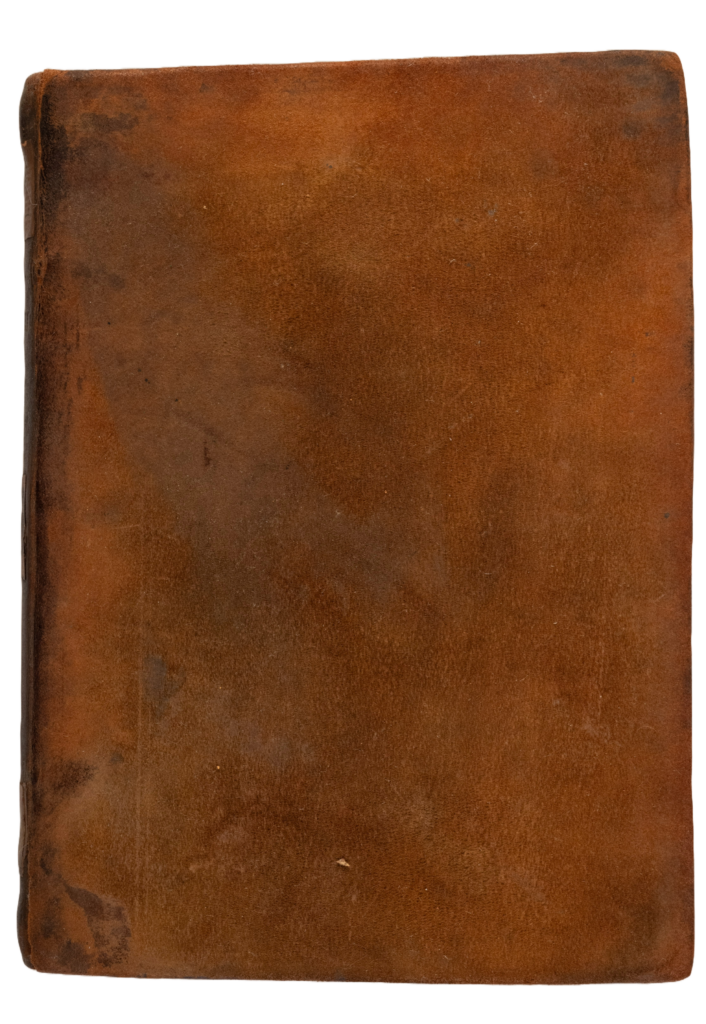

A reversed calf binding looked and felt suede-like, made by turning the flesh side of the skin outside, rather than the hair side.

It was primarily used for utilitarian bindings from the 18th century onwards.

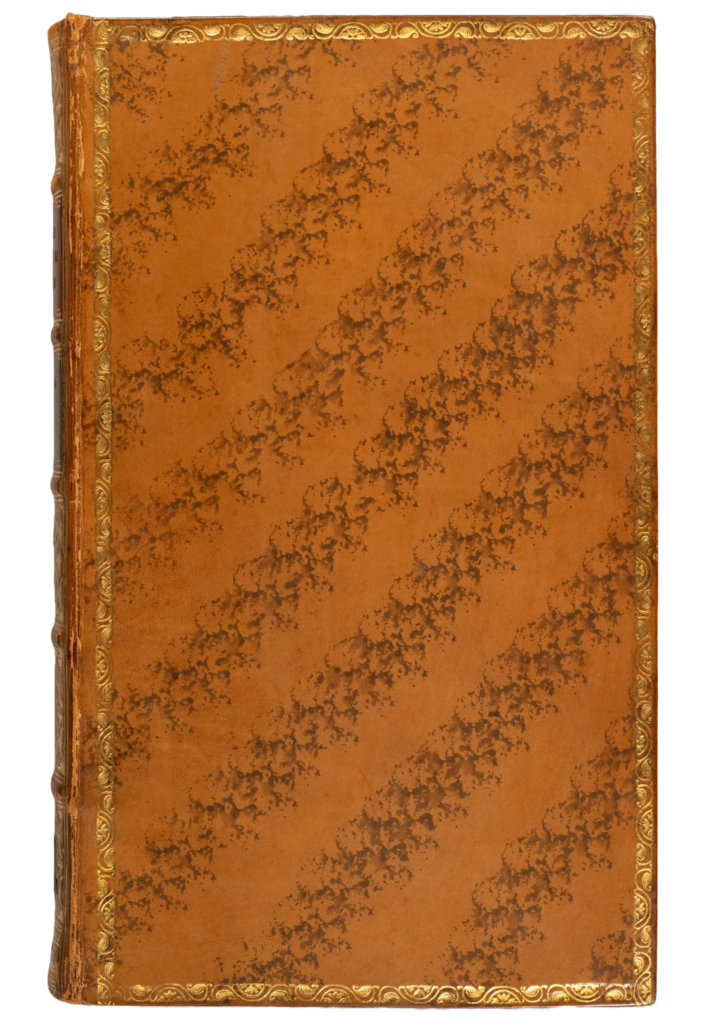

The binding below shows traditional mottling in rows.

The book below clearly shows the soft, suede-like nap, rather than a smooth finish.

Fragmenta Comicorum Graecorum, Collegit et Disposuit.

Augustus Meinke

Berlin, 1839

P001188557

Deus et Rex; sive, Dialogus, quo demonstratur Serenissimimum D. nostrum Jacobum Regem immediate sub Deo …

Richard Mocket

London, 1615

P001353418

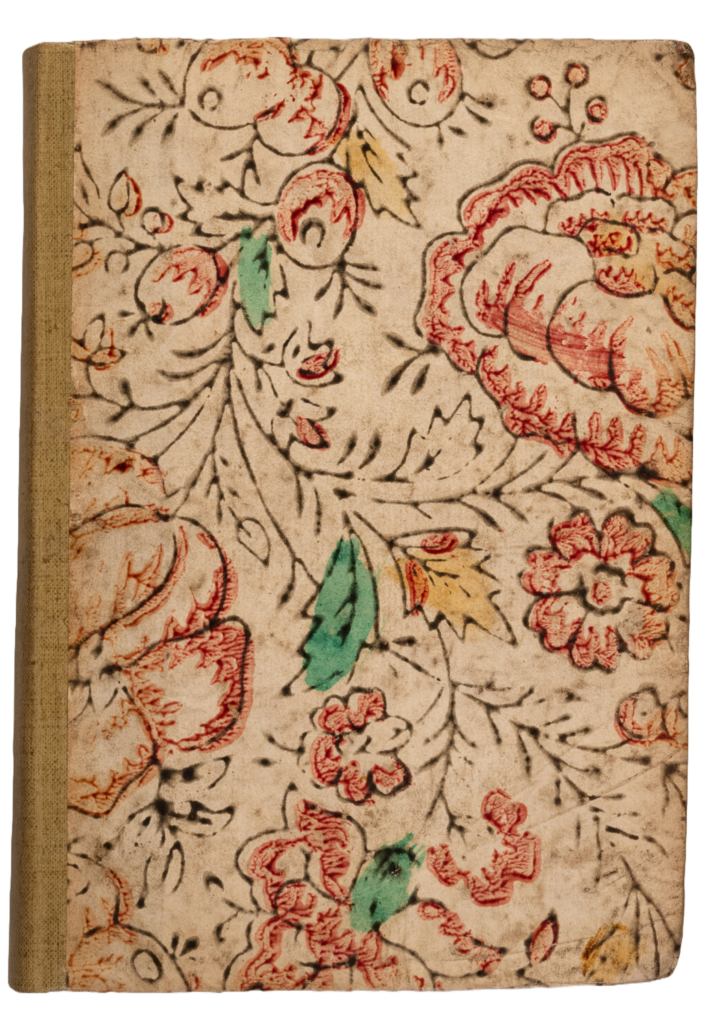

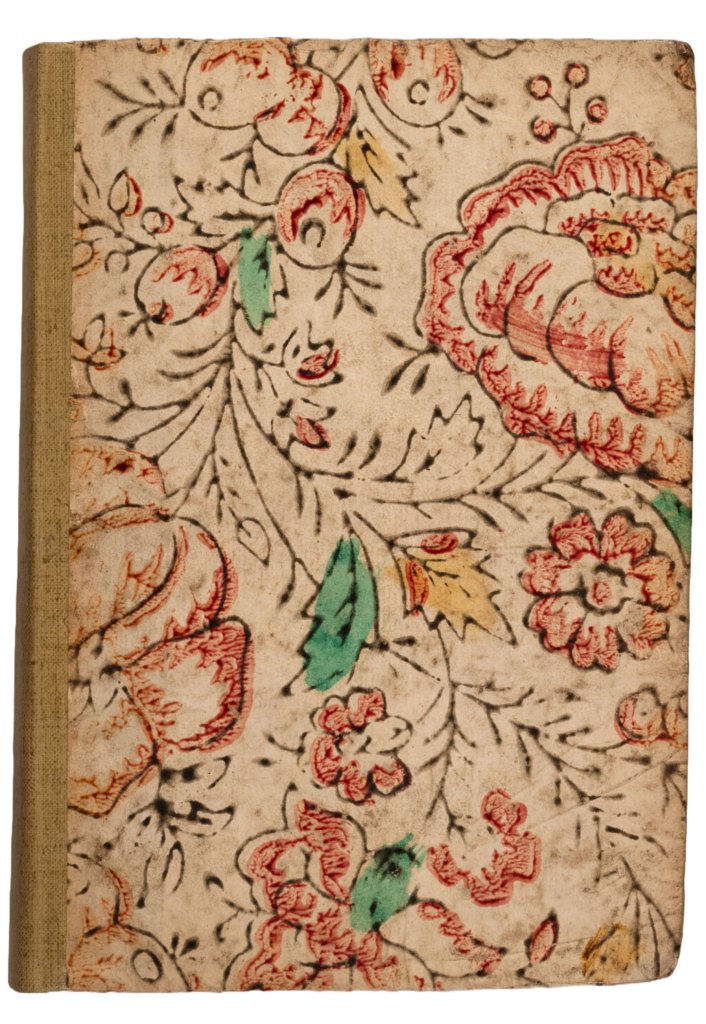

21 | Decorative Papers

21.1 | Block Printed Paper

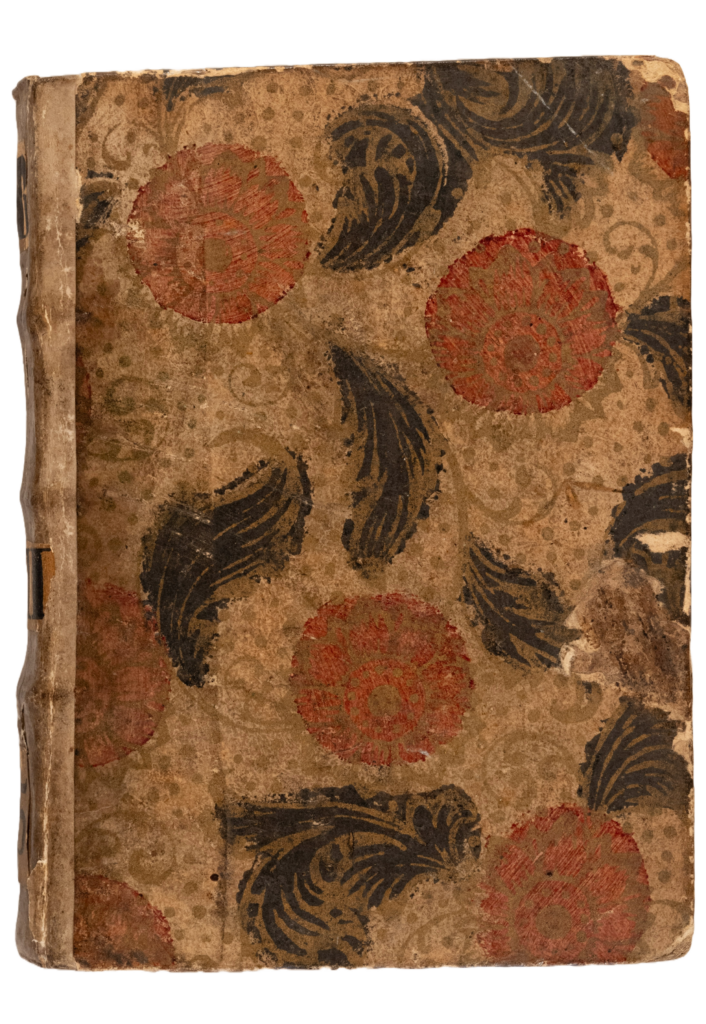

To make block-printed papers, a carved wooden printing block was used to stamp a design onto paper.

For multi-coloured designs, a separate block was used for each colour.

Block-printed papers were extremely popular in the 18th century.

The binding below is covered in a paper, blocked printed with bronze varnish, as well as black and red ink.

The front and back have different papers: the front shows a flower and leaf design in red, black and bronze, the back shows a black hare and goat.

21.2 | Paste Paper

Paste paper was made either by covering a dampened sheet of paper with a paste paint, and manipulating it to create patterns, or by applying paste paint directly to the paper with tools.

There were five main categories of making paste paper:

- Pulled (two sheets coated with paste were placed on top of each other and rubbed, creating a feather effect)

- Drawn, including combed (patterns were drawn into the paste with a tool)

- Daubed (pattern wasdaubed with a sponge into the paste)

- Printed (stamps or woodblocks were pressed onto the pasted sheet, or paste was applied directly to a woodblock. The design was then stamped onto blank paper.)

- Spatter (pasted diluted with water was spattered unto the page and hung while wet)

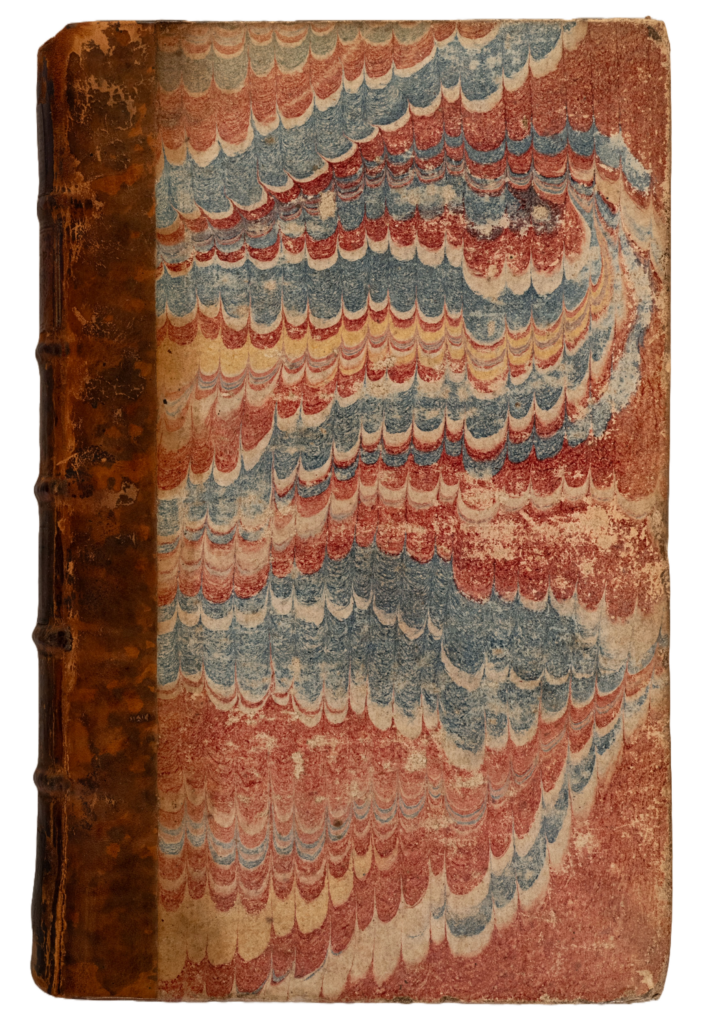

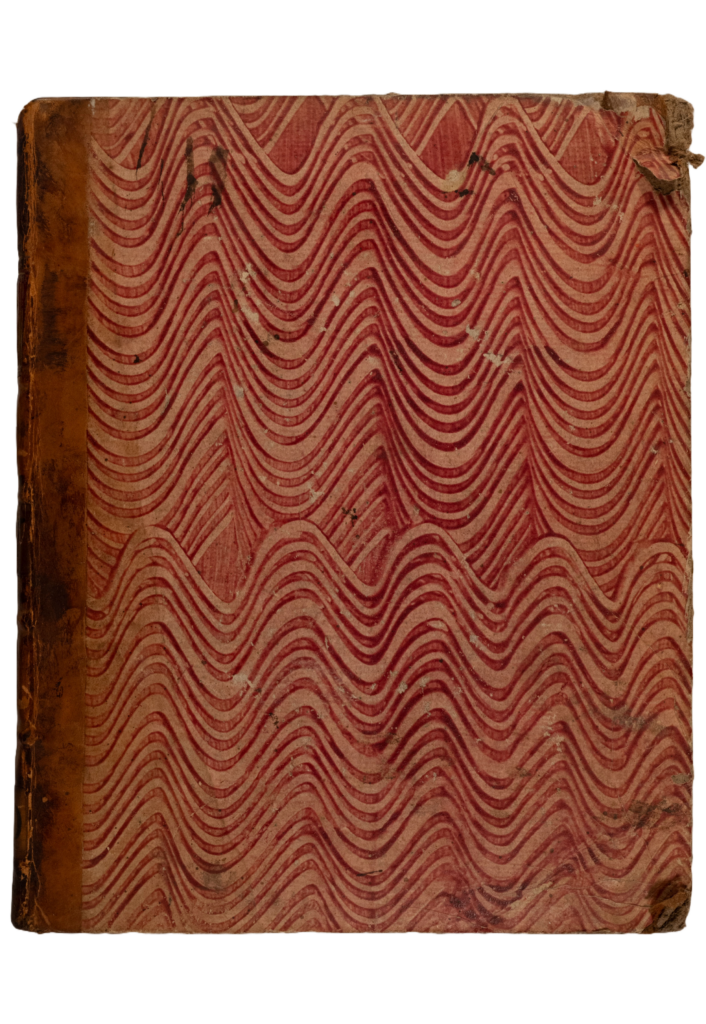

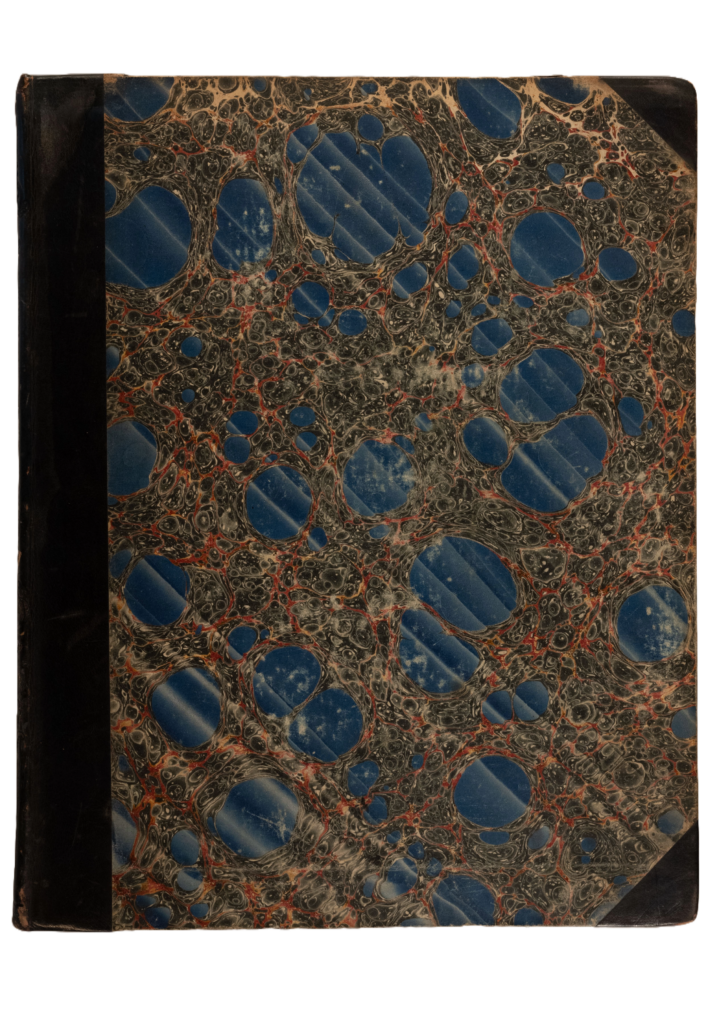

21.4 | Marbled Paper

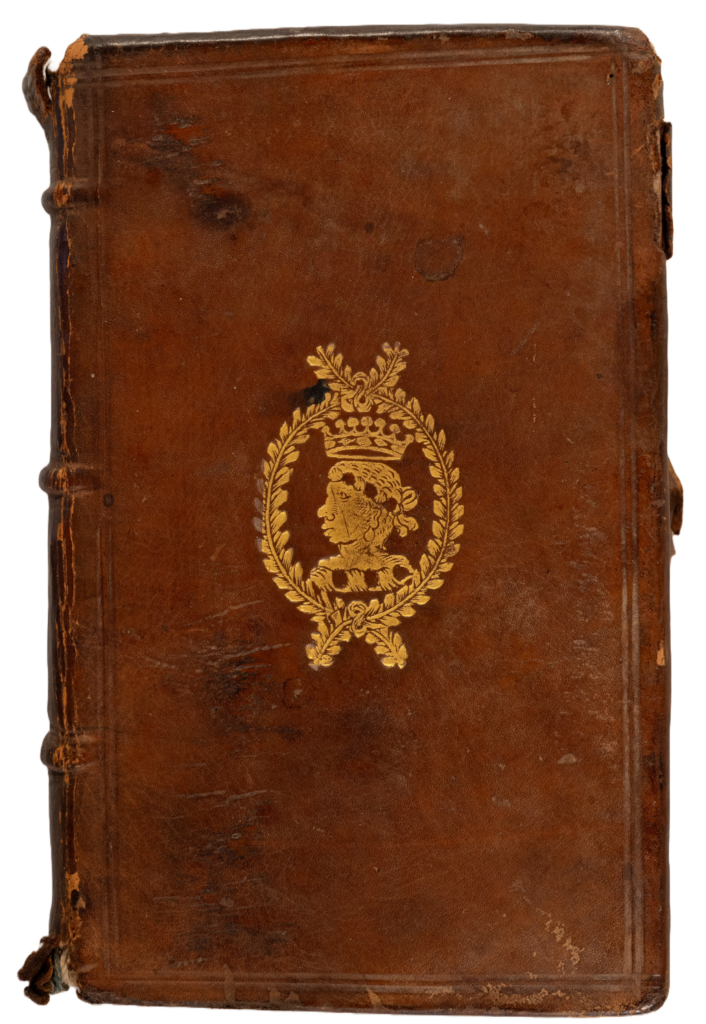

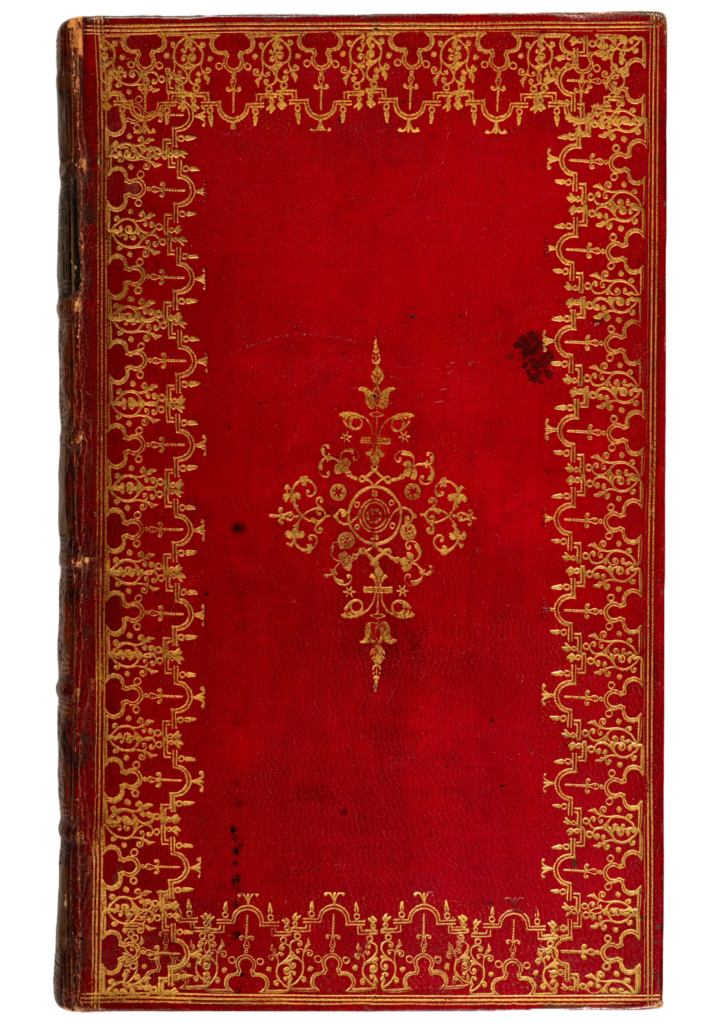

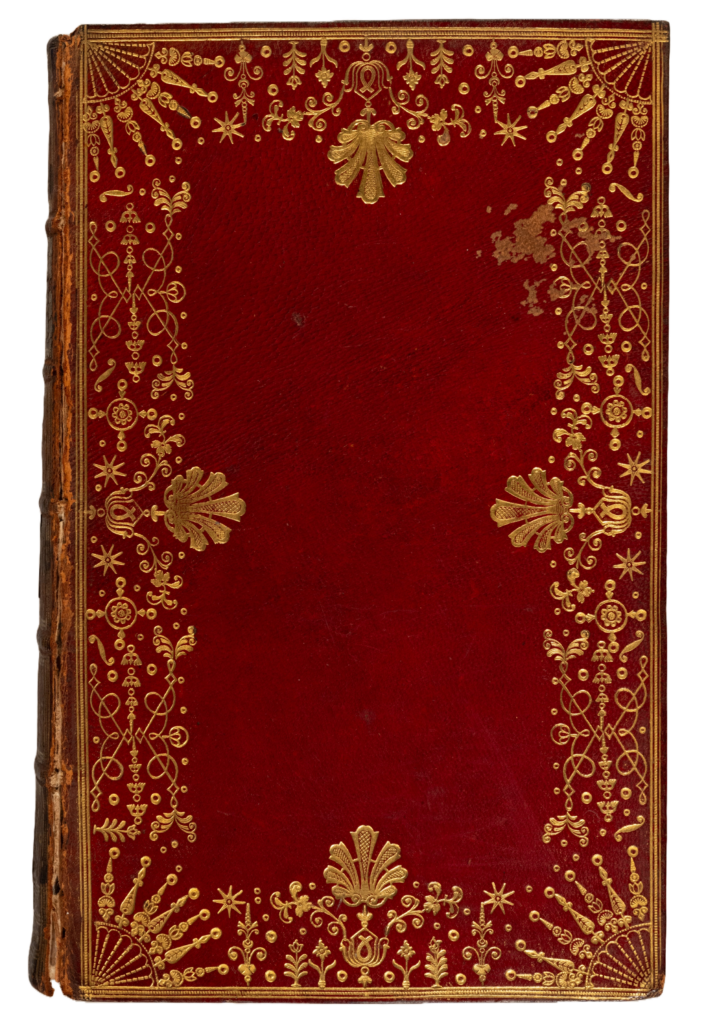

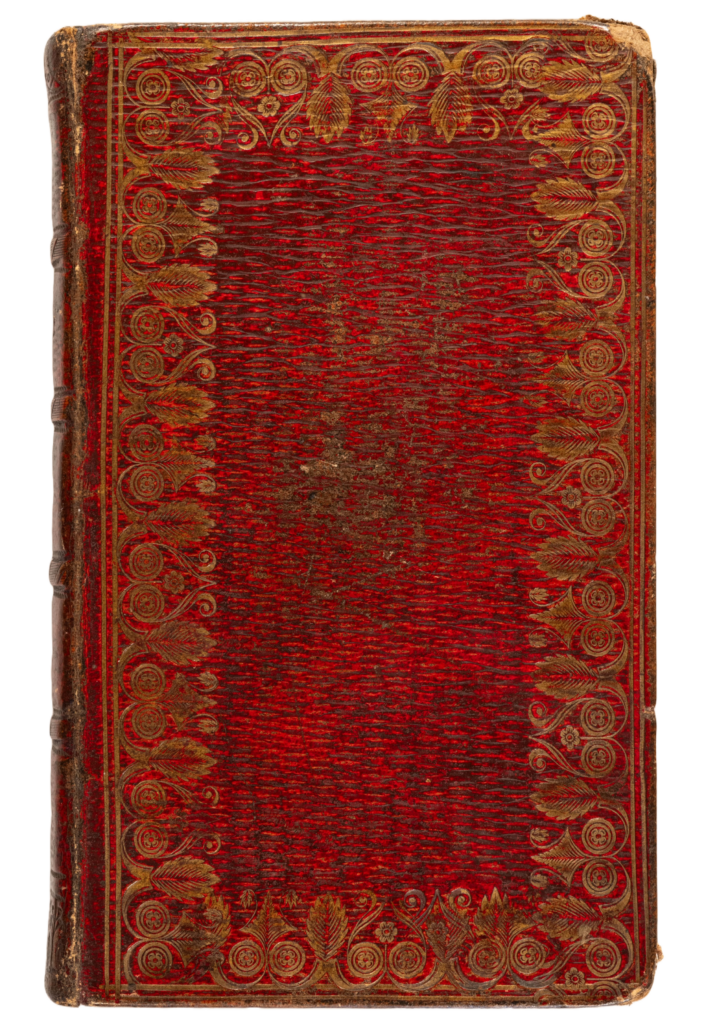

22 | Luxury bindings

Marbled paper was created by adding inks to a shallow tray filled with size, a thick sticky liquid. The inks were then manipulated with combs, rakes or movement into the desired design.

A sheet of paper was then gently placed upon the size, to allow the inks to transfer.

Luxury bindings from late 18th– early 19th century often had simple gold tooling patterns.

Luxury bindings were often made with straight grain Morocco: a goat leather manipulated to create a ripple effect, usually dyed in strong colours.

The name no longer holds a geographic meaning, but simply indicates the binding is made from goatskin.

The binding on display is an example of a Spanish Wave marbled paper.

To create a Spanish Wave, a base pattern is created first. Paper is then gently lowered onto the size, and the tray moved back and forth to agitate the water to create a rippled fabric effect.

The luxury Morocco binding on display clearly shows the ripple effect in the red leather. It is decorated with gold roll decorations around the board edges and gilded book block edges.

Gondola Hills; fairy bay; valley of rills and flowers; legend of the hills, nursery tales in rhyme, the whispering voices of the storm; or, The three antediluvian nymphs, love, grief, and sympathy. Don Alonza and Florinda, or disappointed love: the legend of hills or mountain stream; Column Camp, Alonza Column.

William Arthur Creery

Dublin, 1859

P00122748x

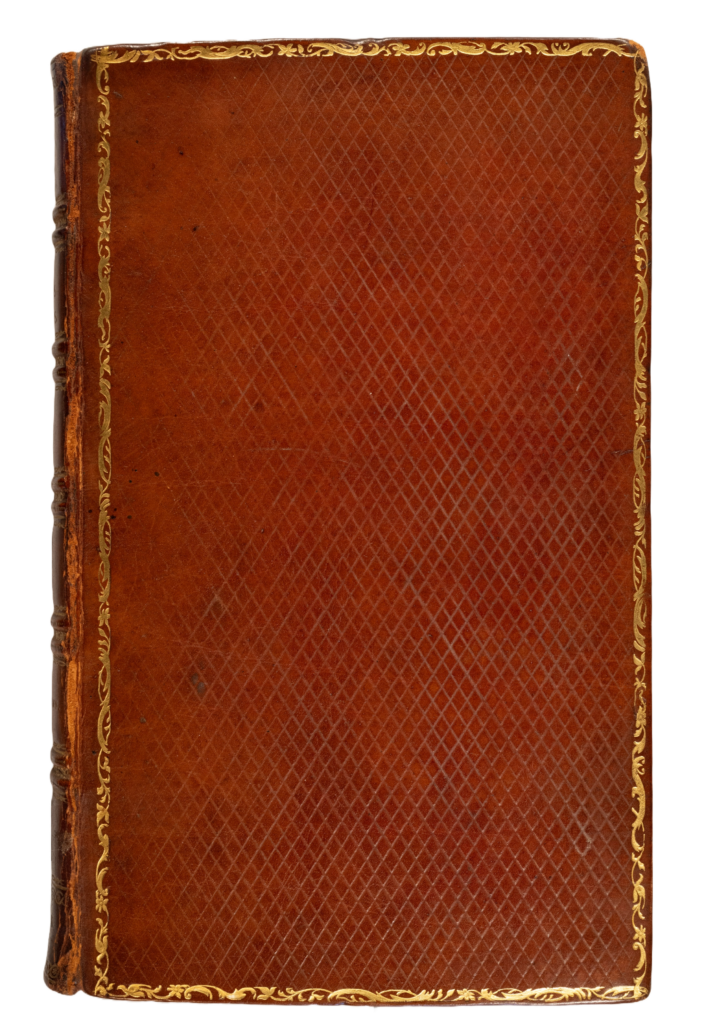

23 | Russia Leather

24.1 | Cloth

Russia leather was made by tanning primarily with willow bark. At the end of the tanning process birch oil was added to keep the leather flexible.

The diamond shaped pattern was originally made with sticks, but later a grooved roll was used. The roll was applied in two different directions to create the pattern. This process was called dicing.

It was popular from the early 18th century through to the early 19th century.

Cloth bindings became popular in the 1800s. Initially they were prepared with a variety of grains to disguise the too-obvious thread marks of cloth bindings.

From 1823 onwards, cloth bindings started being decorated by blocking, instead of tooling. A metal block under pressure and heat could transfer all decorations in one action.

There was a steady invention of cloth decoration techniques:

- 1830s: Blind- and gold-blocking, which could be applied on the same binding.

- 1840s: Ink-blocking, especially in black ink instead of gold, which made decorated cloth bindings cheaper.

- 1850s: Gold- and black blocking were combined.

- 1880s: ‘Silver’ blocking, which was actually aluminium, was developed.

The book on display is a calf Russia leather binding, with the regularly diced diamonds clearly visible. Gold roll decorations around the edges.

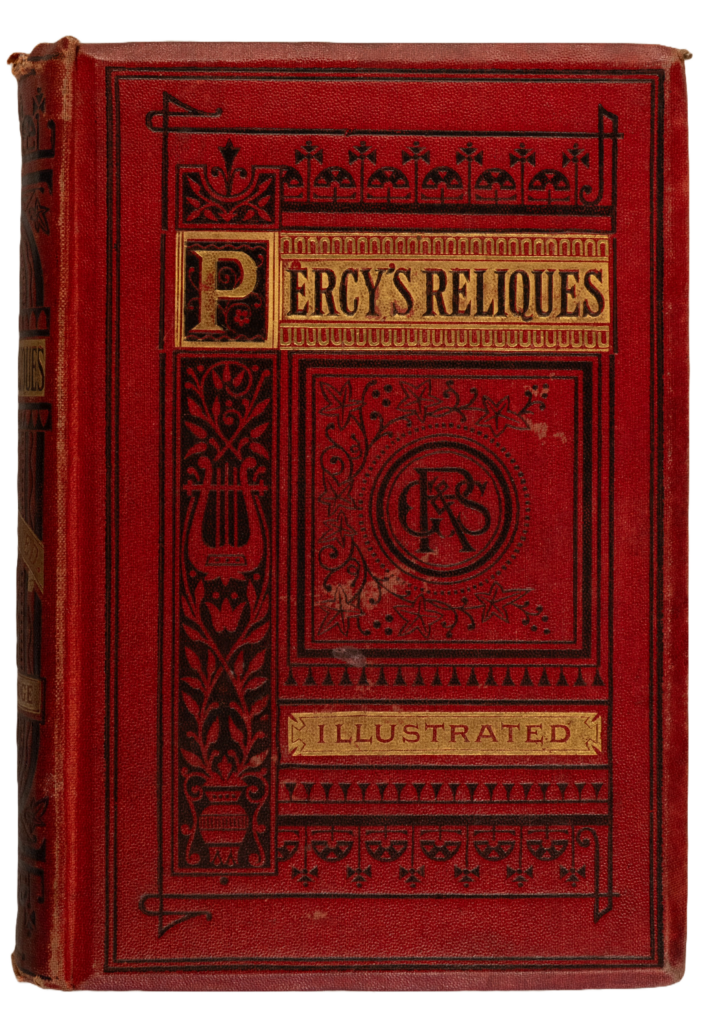

The book below is an 1850s gold and black-blocked binding.

The Works of the Right Reverend Father In God, Joseph Hall, D.D. Successively Bishop of Exeter and Norwich …

Joseph Hall

London, 1808

P00099974

Reliques of Ancient English Poetry …

Thomas Percy

London, 1857

P000999748