This book exhibition showcases several 17th and 18th Century publications on Aesop’s Fables, as well as works inspired by or based on Aesop’s legacy from our collections.

Apart from the New Testament, no other work written in Greek is more widely or better known than Aesop’s Fables. Around 2,500 years ago, it is believed, Greek storyteller and fabulist (creator of fables) Aesop created, and gathered from other sources, hundreds of fables.

Fables are short fictional stories that teach a moral lesson, the so-called moral.

They would feature animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are given human qualities, such as the ability to speak.

Over the centuries, Aesop’s Fables have been translated into many languages and haven often been re-written, according to local culture.

Aesop was a slave and a storyteller, who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BC. During his lifetime he wrote, collected and passed on hundreds of fables. These fables were part of the oral tradition: told as stories to others, who in turn passed the fables on.

Aesop’s Fables were not written down until some centuries after Aesop’s death. The Fables themselves remain well-known to this day, some as stories in their own right, and others in a phrase or saying, such as:

• The Boy Who Cried Wolf;

• The Goose that Laid the Golden Eggs;

• The Lion’s Share;

• The Tortoise and the Hare (Slow and steady wins the race);

• The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse;

• The Fox and the Grapes (Sour grapes).

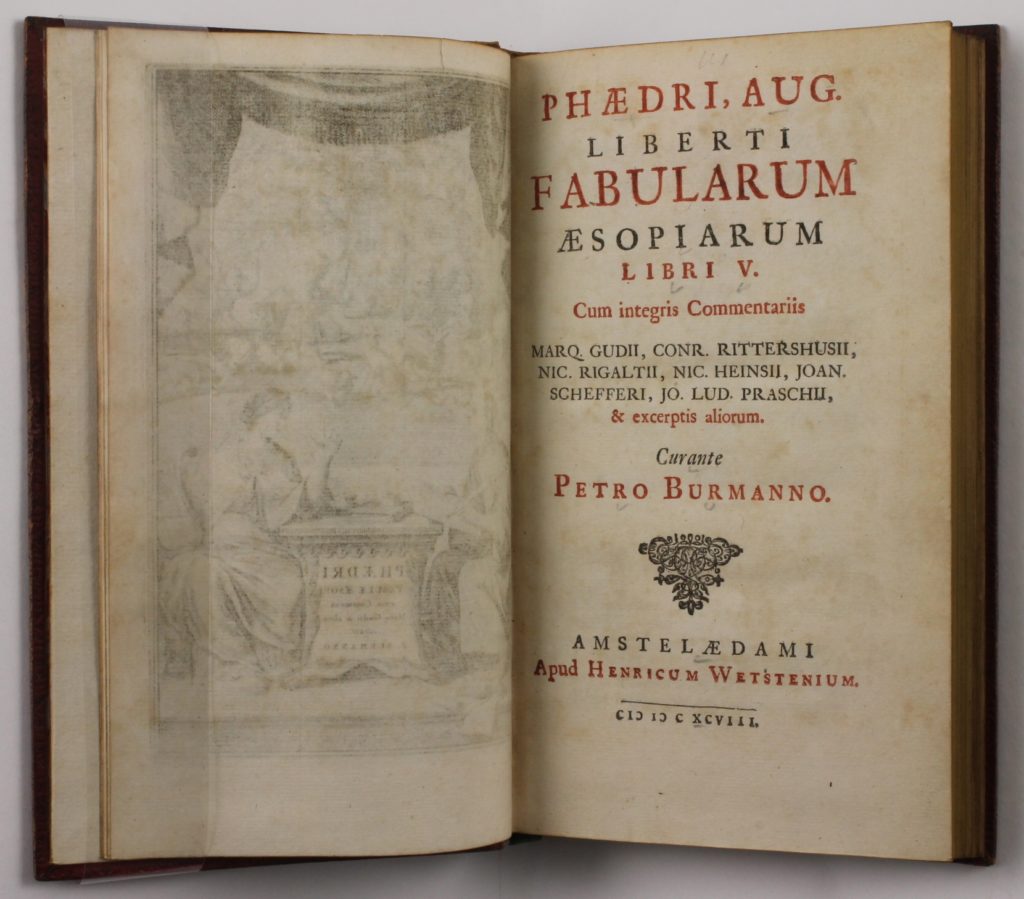

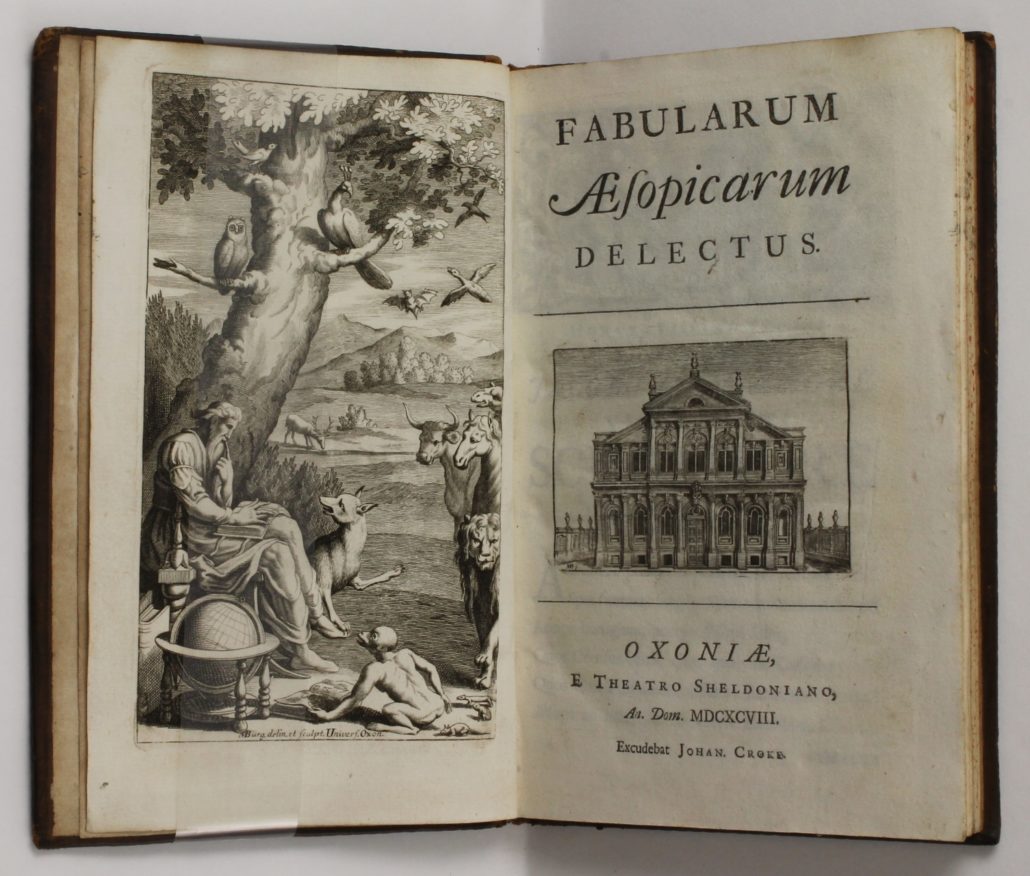

Phaedri Aug. Liberti Fabularum Aesopiarum Libri V: cum integris commentariis Marq. Gudii, Conr. Rittershusii, Nic. Rigaltii, Nic. Heinsii, Joan. Schefferi, Jo. Lud. Praschii et excerptis aliorum Pieter Burman 1698 P00111149x

Phaedrus, a fabulist from the 1st Century BC, compiled the earliest surviving collection of Aesop’s Fables from the ancient world, comprising more than one hundred fables. A manuscript of Phaedrus’ work, dated from the 9th Century, was discovered in France at the end of the 1500s.

Before the century was over, three editions of the manuscript were published by Pierre Pithou as Fabularum Aesopiarum Libri Quinque.

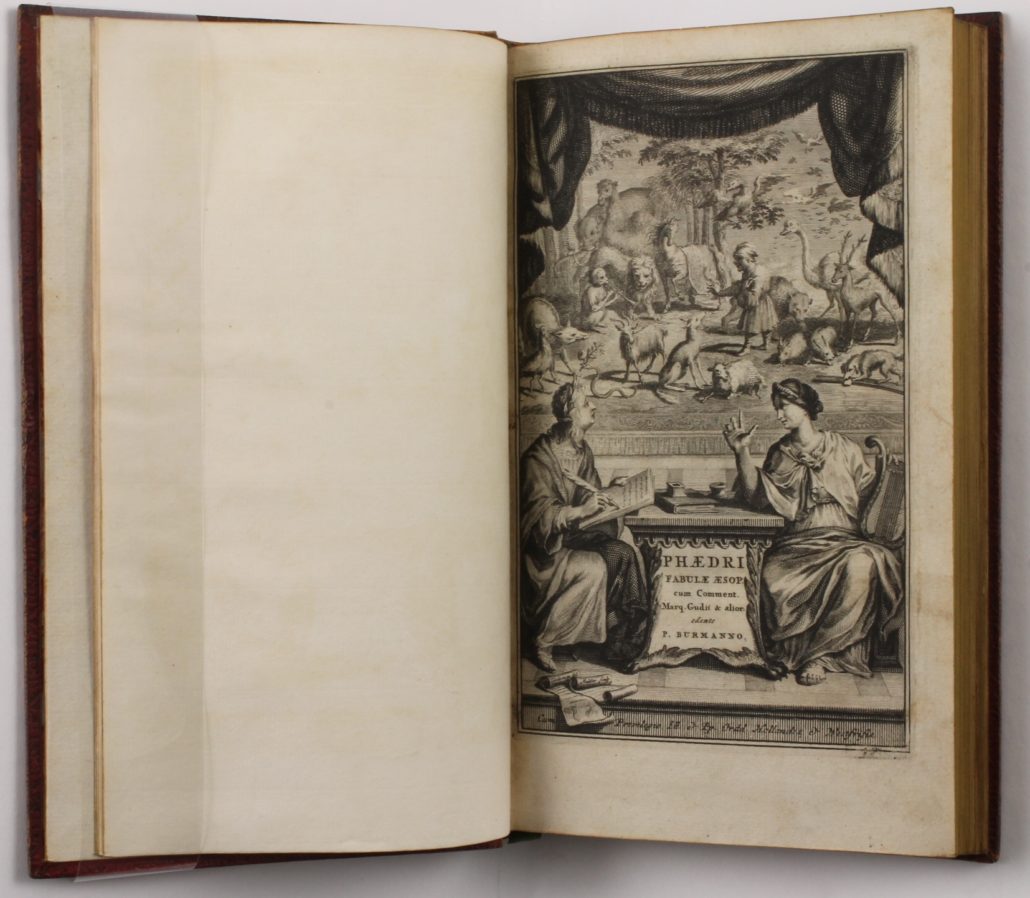

This Pieter Burman edition from a century later, 1698, carries a frontispiece showing the host of animals featuring in Aesop’s Fables.

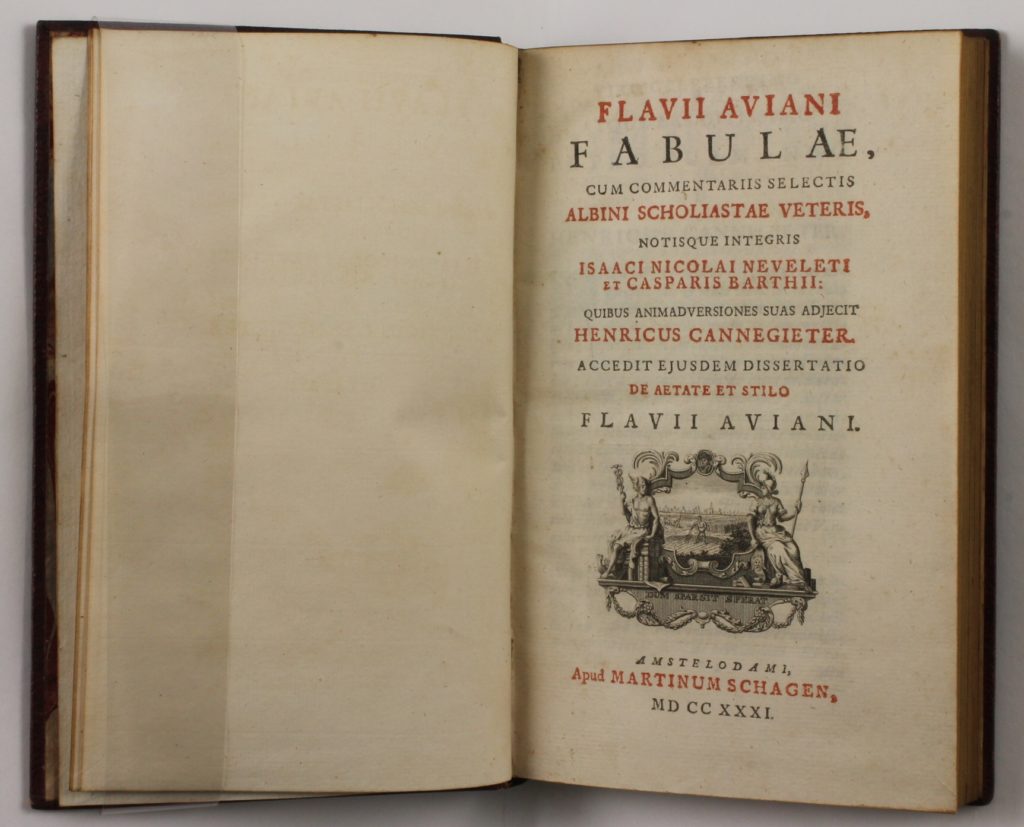

Flavii Aviani Fabulae, Cum Commentariis Selectis Albini Scholiastae Veteris, Notisque Integris Isaaci Nicolai Neveleti Et Casparis Barthii: Quibus Animadversiones Suas Adjecit Henricus Cannegieter. Accedit ejusdem Dissertatio de ætate et stilo Flavii Aviani. Flavius Avianus 1731 P001115215

This early collection of Aesop’s Fables in Latin verse is by the fabulist Avianus (c. 400 AD). His work contains 42 fables, which overlap with the large collection of Aesop’s Fables in Greek, collected and written by Babrius around 200 AD.

Babrius’ fables have a good reputation in style and substance, whereas critics thought that Avianus’ fables were not of the same quality. The importance of Avianus’ work is shown when his work started to be used as a school book.

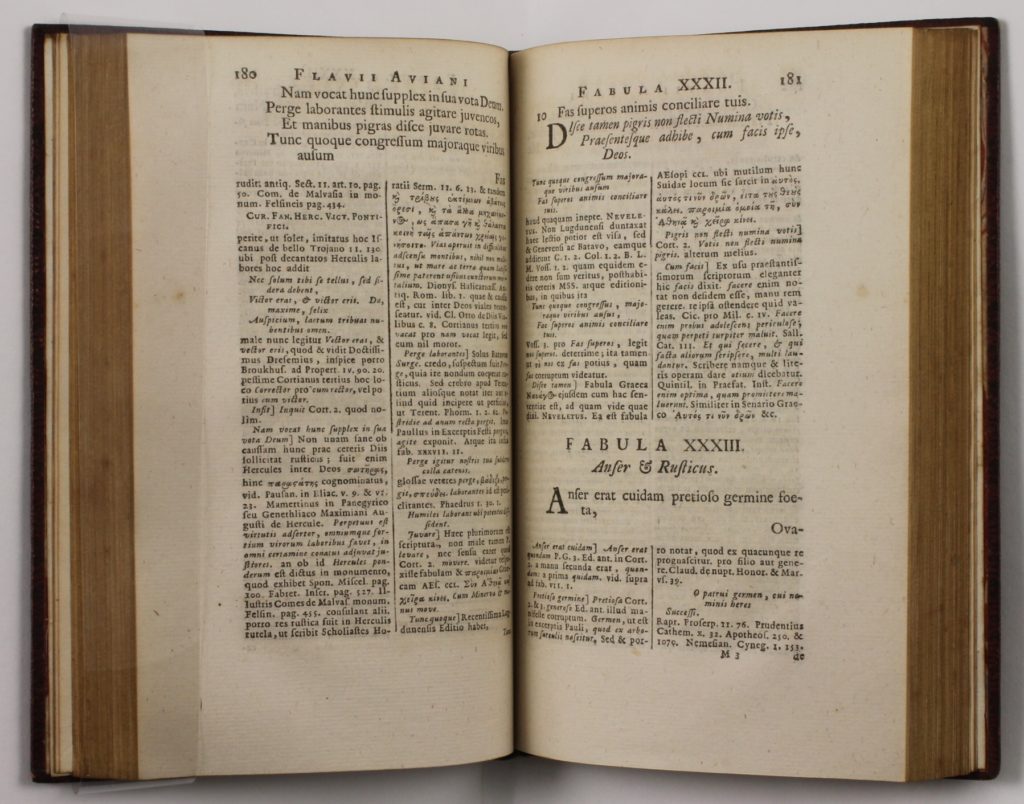

Anser & Rusticus = The Goose with the Golden Eggs

A man had a goose that laid a golden egg for him each and every day. The man was not satisfied with this daily profit, and instead he foolishly grasped for more. Expecting to find a treasure inside, the man slaughtered the goose. When he found that the goose did not have a treasure inside her after all, he remarked to himself, “While chasing after hopes of a treasure, I lost the profit I held in my hands!”

MORAL

People often want more than they need and subsequently lose the little they have.

From Aesop’s Fables. A New Translation by Laura Gibb (2002)

Aesopi Phrygis Fabulæ [...] 1618-1700 P001407631

During the Renaissance, interest in Latin literature experienced a revival. Authors such as the Italian Laurentius Abstemius (c. 1440–1508) began collecting stories from the Classical period.

Abstemius’ most well-known work is Hecatomythium (1485), a collection of a hundred fables in Latin.

He wrote most of the fables himself, but also included thirty-three of Aesop’s Fables. The work on display contains his fables, Aesop’s Fables and the fables by Avianus, the Latin fabulist from c. 400 AD.

De Lupo Ovis Pelle Induto Qui Gregem Devorabat = The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

A wolf once decided to change his nature by changing his appearance, and thus get plenty to eat. He put on a sheepskin and accompanied the flock to the pasture. The shepherd was fooled by the disguise. When night fell, the shepherd shut up the wolf in the fold with the rest of the sheep and as the fence was placed across the entrance, the sheepfold was securely closed off. But when the shepherd wanted a sheep for his supper, he took his knife and killed… the wolf.

MOTTO

From Aesop’s Fables. A New Translation by Laura Gibb (2002)

Seek to do harm and harm will come to you.

The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing Dirk Stoop 1665 P002474475 Illustration to John Ogilby's The Fables of Æsop Paraphras'd in Verse: Adorned with Sculpture and Illustrated with Annotations.

Jean de La Fontaine collected fables from a wide variety of sources, both Western and Eastern, and translated them into French verse. The first edition was published in 1668, and continued to be published until 1694.

The Fables are now considered classics of French literature. De La Fontaine injected Fables with humour and irony, originally aiming the stories at adults. At a later stage, however, they were used in schools and became required reading for school children.

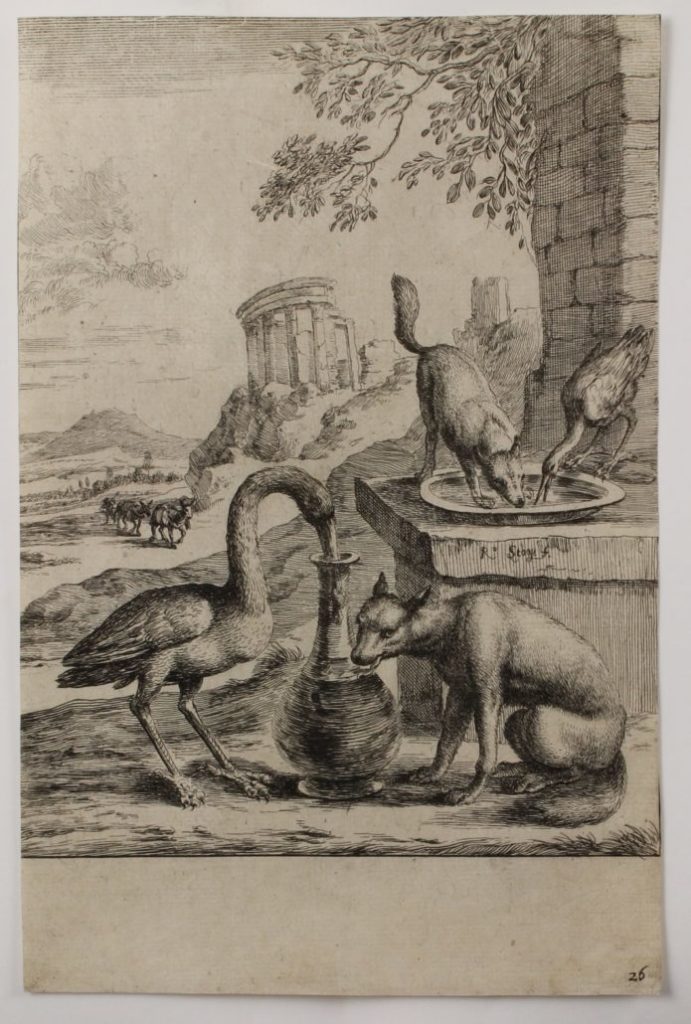

Le Renard & la Cicogne = The Fox and the Stork

A Fox invited a Stork to dinner, at which the only fare provided was a large flat dish of soup. The Fox lapped it up with great relish, but the Stork with her long bill tried in vain to partake of the savoury broth.Her evident distress caused the sly Fox much amusement. But not long after the Stork invited him in turn, and set before him a pitcher with a long and narrow neck, into which she could get her bill with ease.

Thus, while she enjoyed her dinner, the Fox sat by hungry and helpless, for it was impossible for him to reach the tempting contents of the vessel.

MORAL: Treat others as you would wish yourself to be treated.

From Aesop’s Fables: A New Translation by V. S. Vernon Jones with illustrations by Arthur Rackham (1912)

The Fox and the Stork Dirk Stoop 1665 P002474476 Illustration to John Ogilby's The Fables of Æsop Paraphras'd in Verse: Adorned with Sculpture and Illustrated with Annotations.

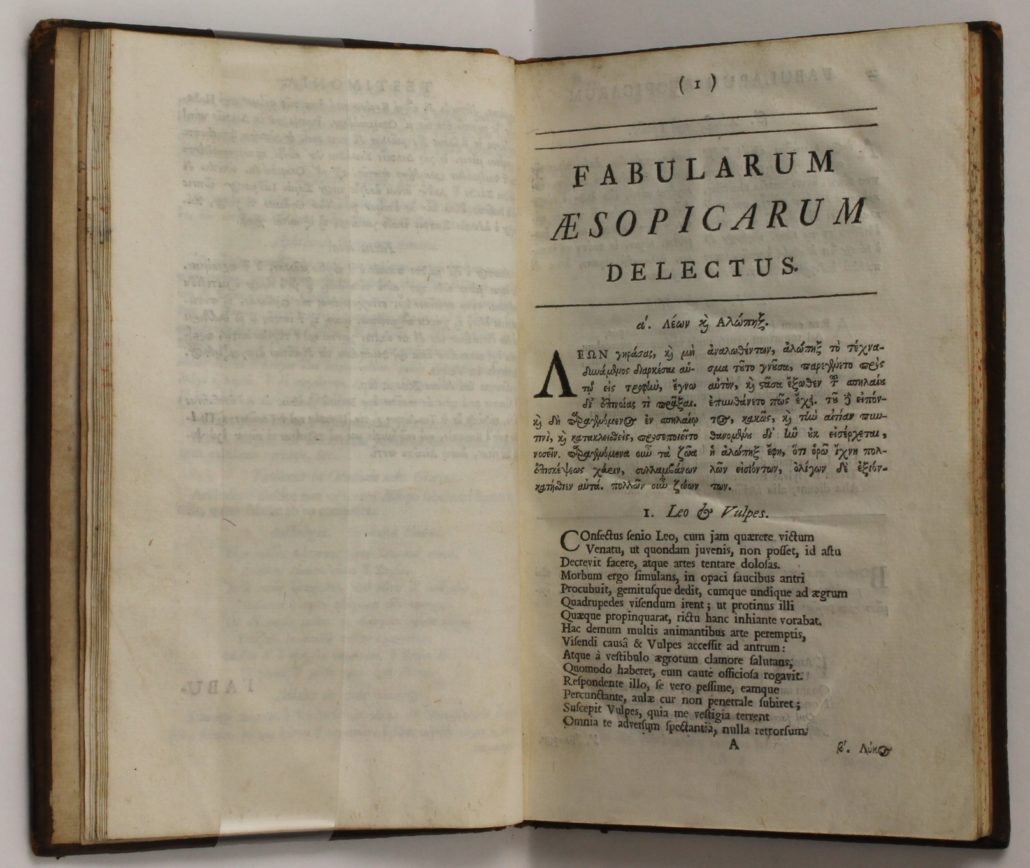

Fabularum Aesopicarum delectus Anthony Alsop 1698 P001411515

Another large edition of the Fables in Latin was published by Anthony Alsop.

In Alsop’s Fabularum Aesopicarum delectus, most of the Fables are accompanied by text in Greek, a handful in Hebrew and Arabic, and the final fables only in Latin.

In this edition the text of the Fables is given without highlighting a moral.

Wolf ende Crane = The Wolf and the Crane Marcus Gheeraerts 1567 P002474174 Illustration to Eduwaert de Dene's edition of Aesop’s Fables, De Warachtighe Fabulen der Dieren.

Lupus & Grus = The Wolf and the Crane

A Wolf once got a bone stuck in his throat. So he went to a Crane and begged her to put her long bill down his throat and pull it out. “I’ll make it worth your while,” he added. The Crane did as she was asked, and got the bone out quite easily. The Wolf thanked her warmly, and was just turning away, when she cried, “What about that fee of mine?” “Well, what about it?” snapped the Wolf, baring his teeth as he spoke; “You can go about boasting that you once put your head into a Wolf’s mouth and didn’t get it bitten off. What more do you want?”

MORAL

From Aesop’s Fables: A New Translation by V. S. Vernon Jones with illustrations by Arthur Rackham (1912)

Help only those who deserve it.

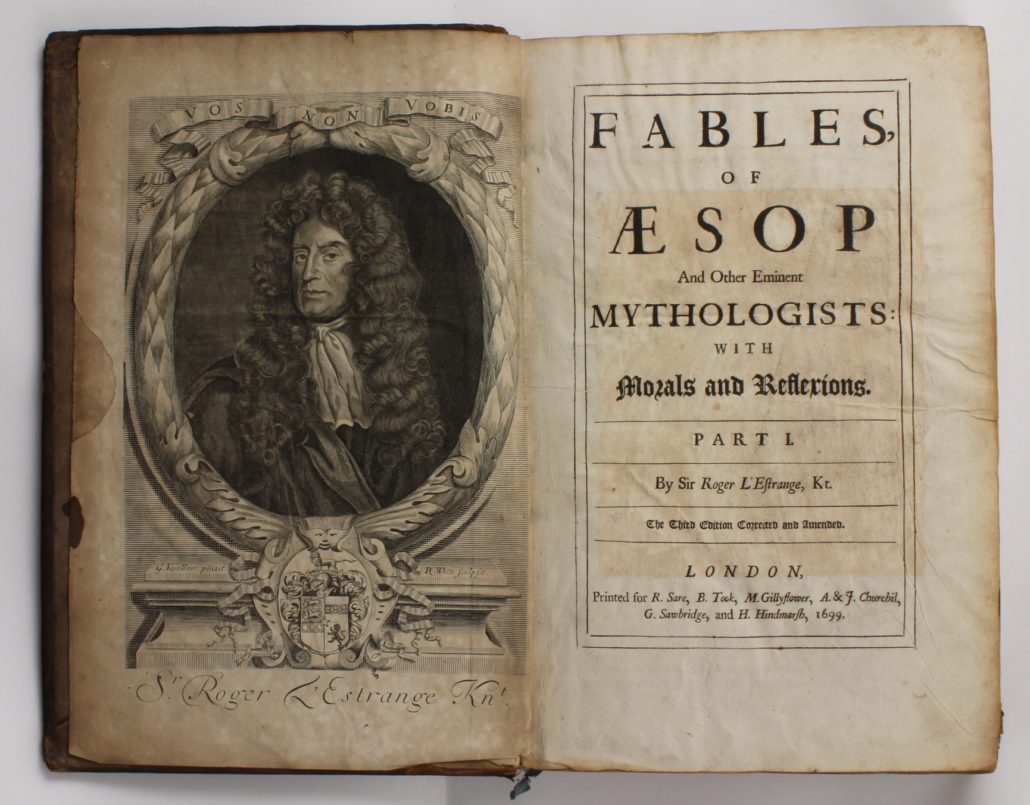

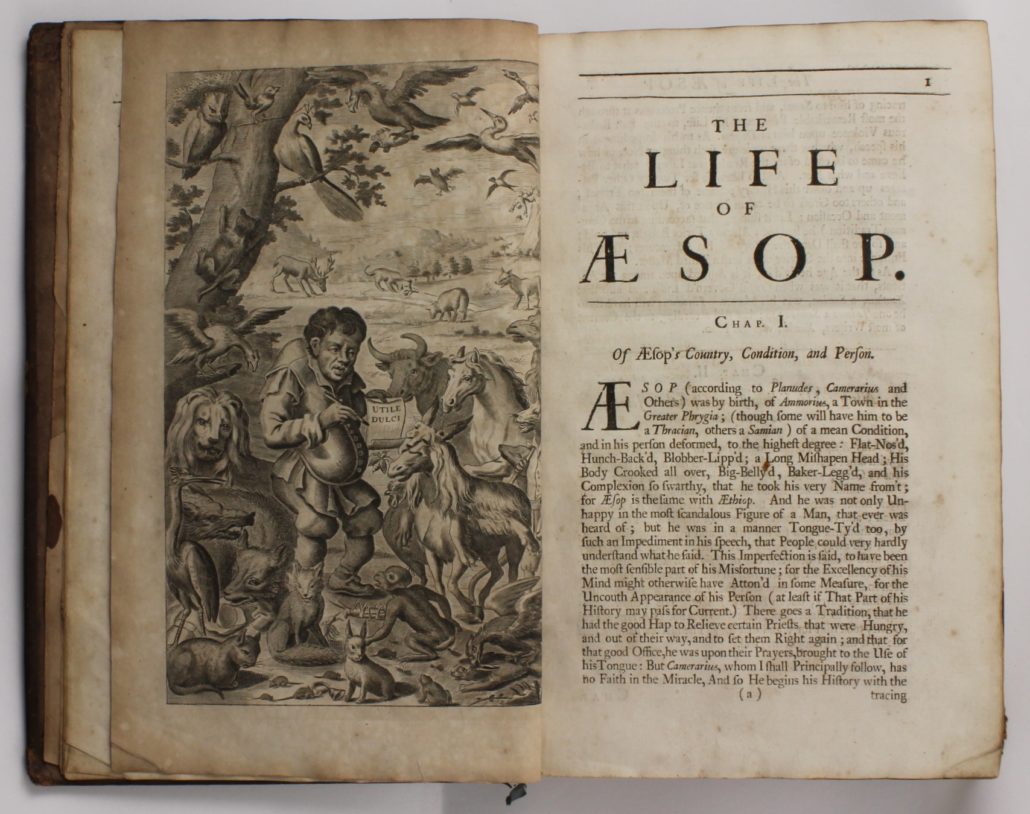

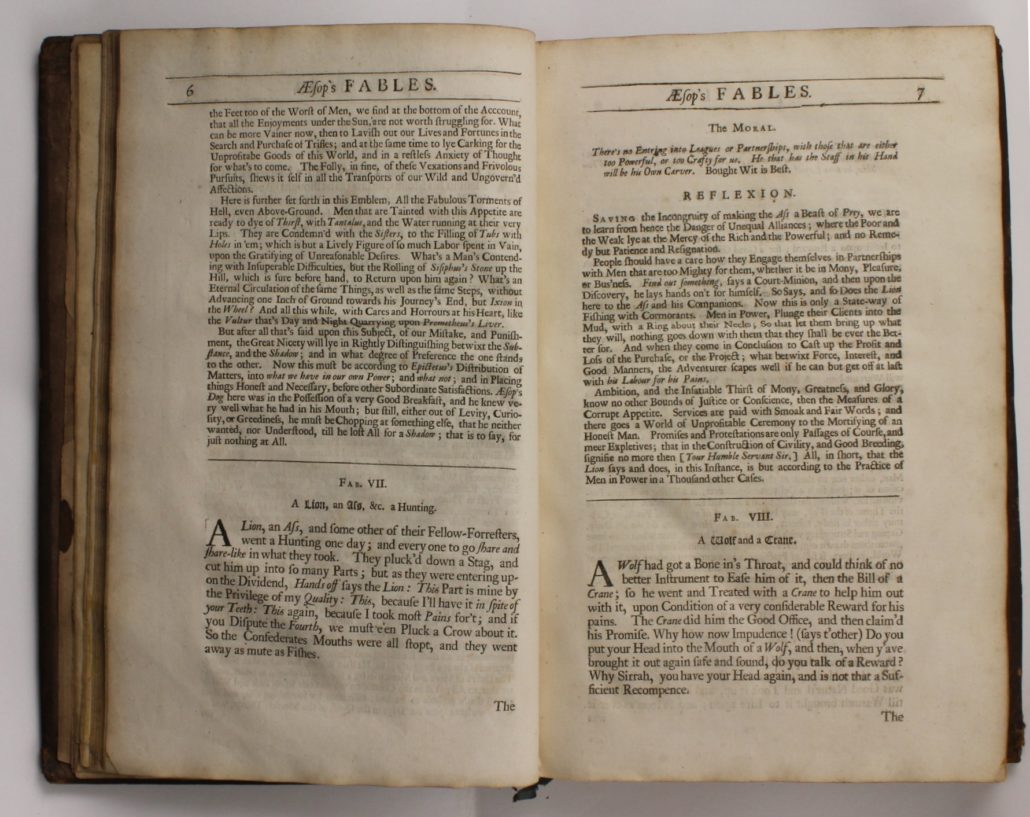

Fables, of Æsop and other eminent mythologists: with morals and reflexions. Roger L’Estrange 1699 P001381993

The first English version of Aesop’s Fables, specifically intended for children, was published by Sir Roger L’Estrange in 1692. L’Estrange had complained that the book on fables that was normally used in schools, Rhapsody of Fables, was unsuitable for education.

[…] the Boys Break their Teeth upon the Shells, without ever coming near the Kernel. They Learn the Fables by Lessons, and the moral is the least part of our Care in a Childs Institution: [. . . ] the Doctrine it self, [. . . ] falls Infinitely short of the Vigour and Spirit of the Fable.

In his publication, each fable is accompanied by a moral and a reflection. This format would become the standard for fable collections for the next century.

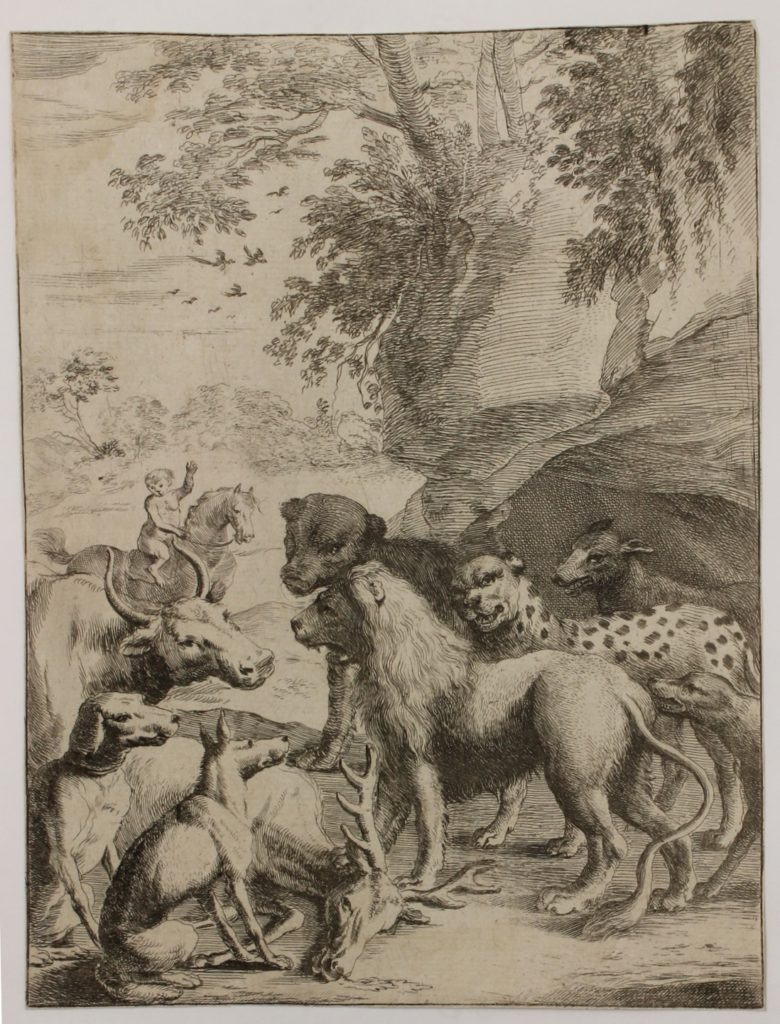

A Lion, an Ass &c a Hunting = The Lion, The Cow, The She-Goat And The Sheep = A Lion’s Share

A cow and a she-goat and a long-suffering sheep decided to become the lion’s companions. They went into the forest together and there they caught an extremely large stag which they divided into four portions. Then the lion said, “I claim the first portion by right of my title, since I am called the king; the second portion you will give me as your partner; then, because I am strongest, the third portion is mine . . . and woe betide anyone who dares to touch the fourth!” In this way the wicked lion carried off all the spoils for himself.

MORAL

From Aesop’s Fables. A New Translation by Laura Gibb (2002)

An alliance made with the high and mighty can never be trusted.

The Lion’s Share Dirk Stoop 1665 P002474260 llustration from John Ogilby's The Fables of Æsop Paraphras'd in Verse: Adorned with Sculpture and Illustrated with Annotations.

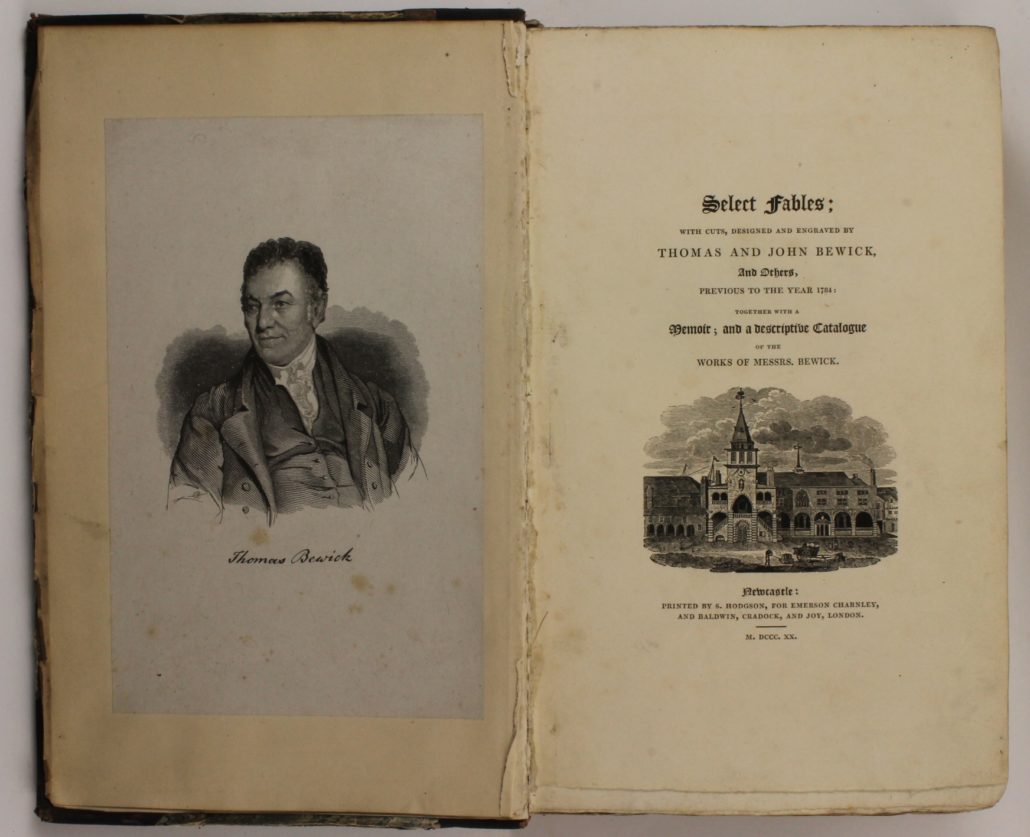

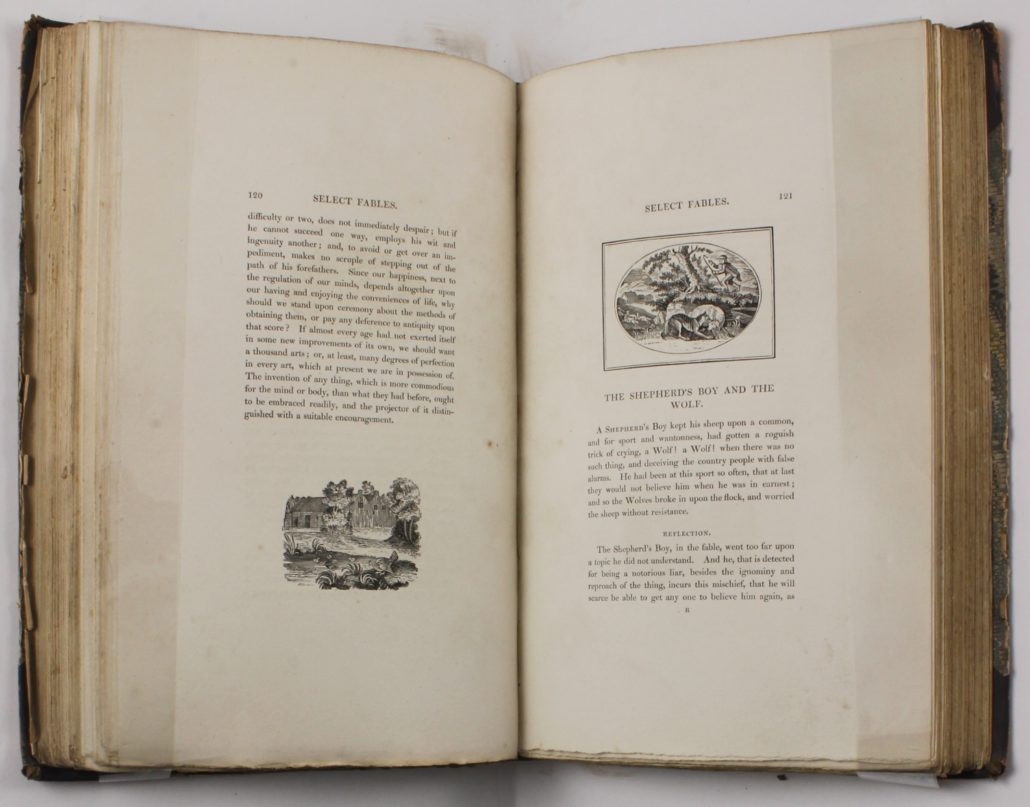

Select Fables, with cuts, designed and engraved by Thomas and John Bewick, and others, previous to the year 1784; together with a memoir, and a descriptive catalogue of the works of Messrs. Bewick Thomas Bewick 1820 P001245585

This edition of selected Fables is a good example of the standard L’Estrange set for the publication of fables.

An engraving accompanies the story, as well as a reflection on what the moral of the story is.

The Boy who cried “Wolf”

There was a boy tending the sheep who would continually go up to the embankment and shout, “Help, there’s a wolf!” The farmers would all come running only to find out that what the boy said was not true.Then one day there really was a wolf but when the boy shouted, they didn’t believe him and no one came to his aid. The whole flock was eaten by the wolf.

MORAL

There is no believing a liar, even when he speaks the truth.