The United Nations General Assembly declared 2022 the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture (IYAFA 2022).

Artisanal fisheries can be subsistence fisheries or small-scale commercial fisheries, providing fish for local consumption or export. They involve fishing households (as opposed to large commercial companies), using small amounts of capital and energy, small fishing vessels (if any), making short fishing trips, close to shore, mainly for local consumption.

In this exhibition we will look at the history of early fishing activity around the British Isles, starting with the first mention in the early Middle Ages right up to the eighteenth century.

People worldwide have been fishing for food and income since prehistoric times. This was no different for the inhabitants of the coastal and river areas of the Island of Ireland!

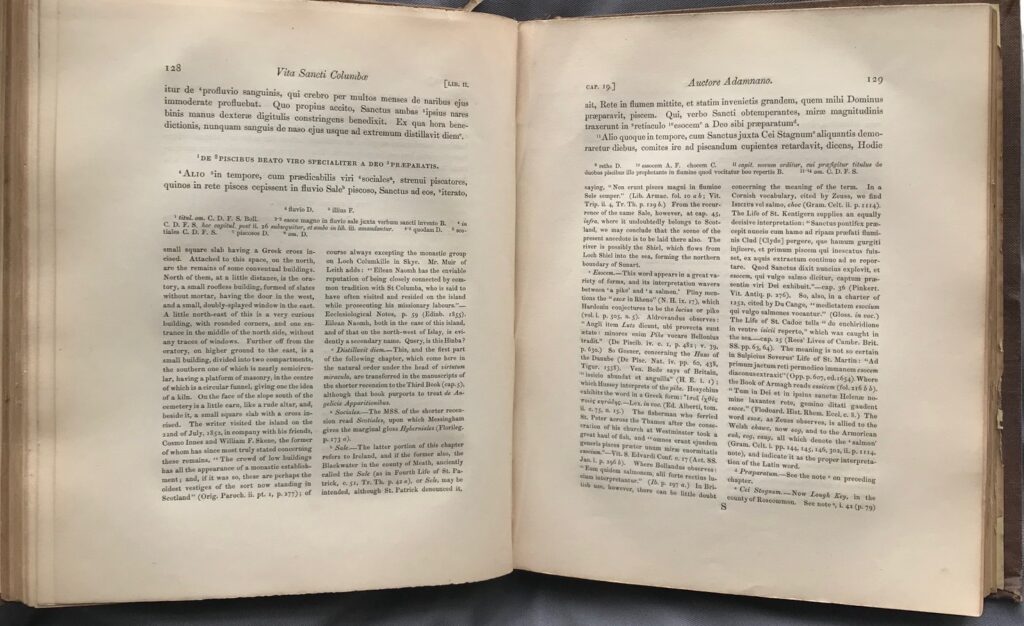

The Life of St Columba, founder of Hy recounts a very early mention of fishermen in two stories relating to Saint Columba of Columcille (521-597).

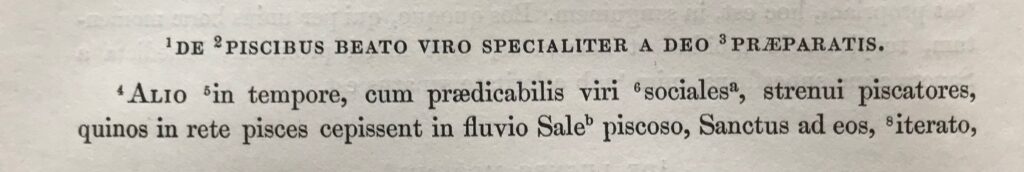

Of the Fishes which were specially provided by God for the blessed man.

… when some hardy fishermen… had taken five fish in their net in the river Sale which abounds in fish, the saint said to them, “Try again,” said he; “cast thy net into the stream, and you shall at once find a large fish which the Lord has provided for me.” …

… he delayed his companions when they were anxious to go a-fishing, saying: “No fish will be found in the river today or to-morrow; but on the third day I will send you, and you shall find two large river-salmon taken in the net.” And so… they cast their nets, and landed two, of the most extraordinary size, which they found in the river which is named Bo (the Boyle). …

Click on the images to see a full size version

The Life of St Columba, founder of Hy ; written by Adamnan … Saint Adamnan, Author; William Reeves, Editor 1857 P001217255

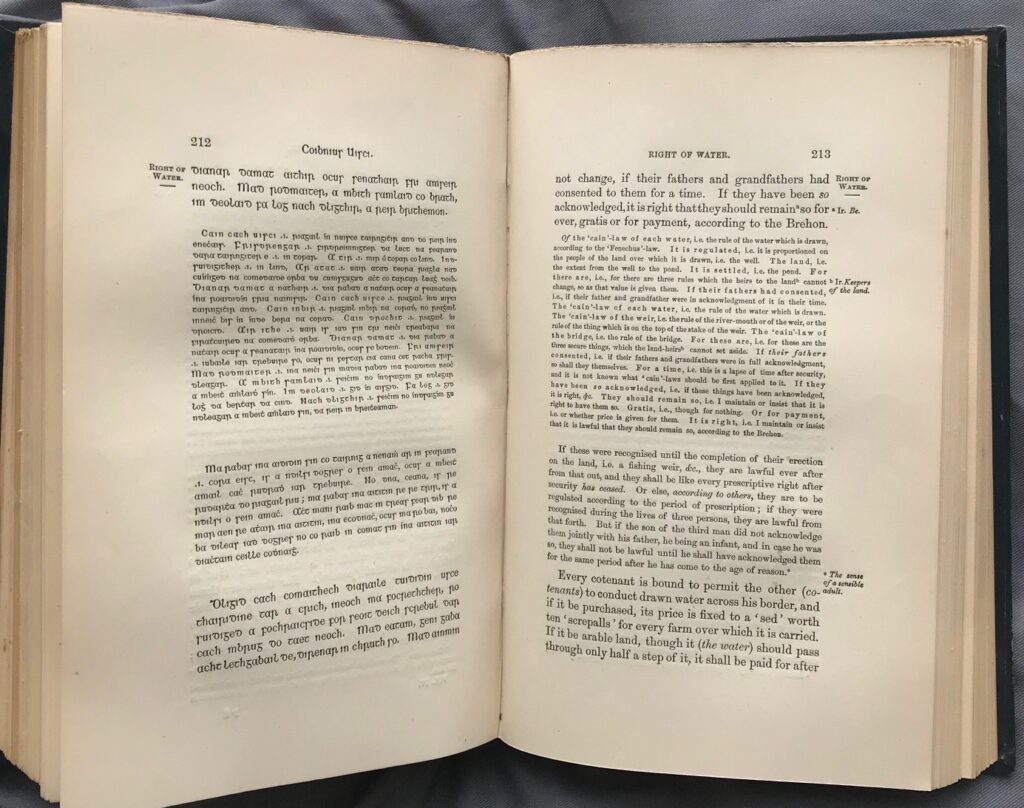

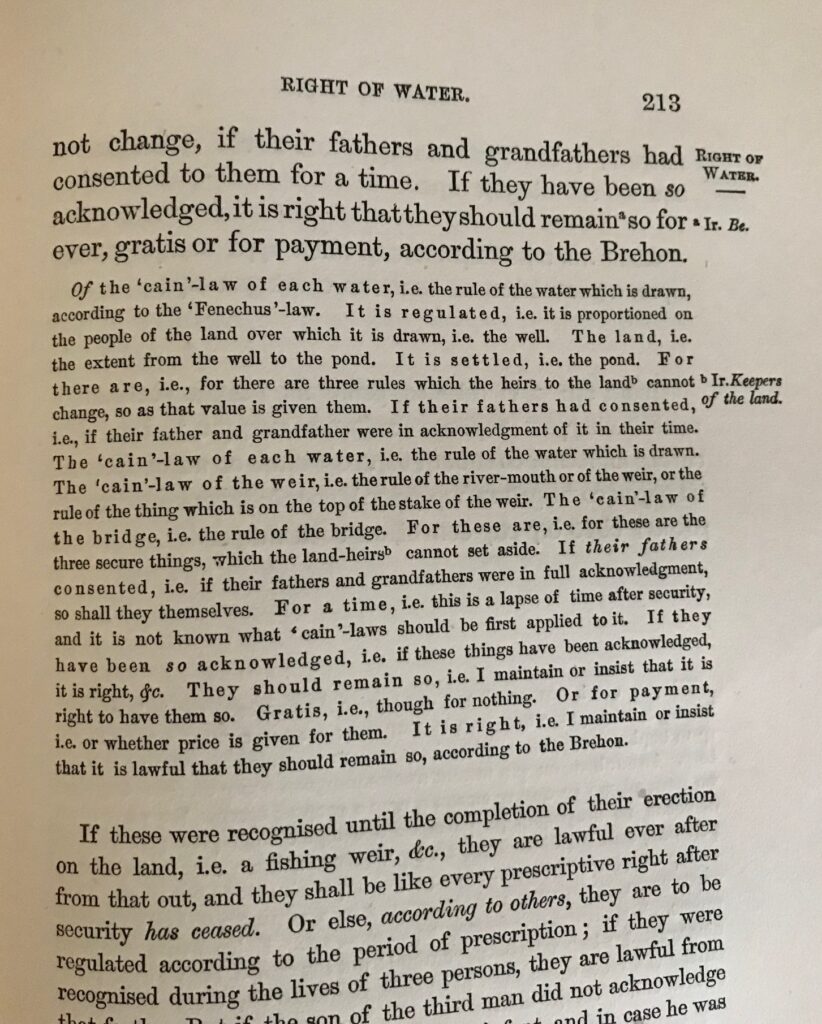

The use of a very early method of fishing, fishing using weirs, can be found in the Brehon laws, or the Early Irish Laws. These laws date back to the seventh and eighth centuries.

The laws refer, amongst others, to the right of fishing and the use of fishing weirs.

If these were recognised until the completion of their erection on the land, ie. a fishing weir, … , they are lawful ever after from that out, and they shall be like every prescriptive right after security has ceased …

To make a fishing weir, a man-made structure was placed across a stream or at the edge of a tidal area. Fish swimming along with the current were then caught in the weir.

Fishing weirs were usually only used for small-scale fishing. People fished to produce food for the family, and perhaps to sell any extras at the local markets.

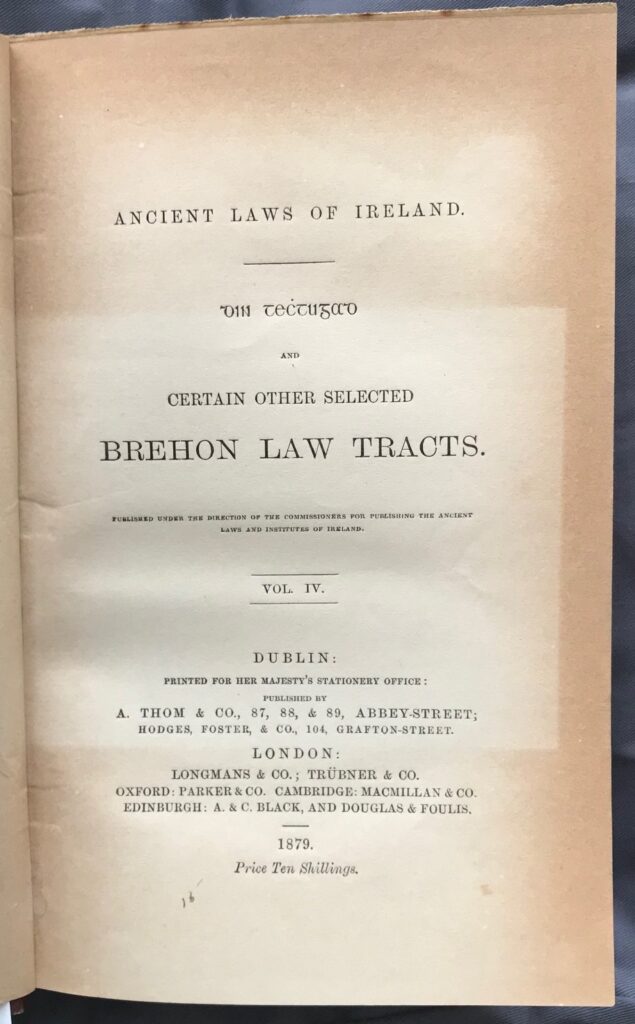

Din Tectugad and Certain Other Selected Brehon Law Tracts. Alexander George Richey, Editor 1879 P001214043

From the eleventh century onwards towns started growing steadily, along with the demand for fish in the markets.

As salting and smoking methods for preserving fish improved, fishermen were able to travel further to fish. Many fishermen therefore moved from freshwater fishing to sea fishing. The number of commercial fisheries subsequently increased.

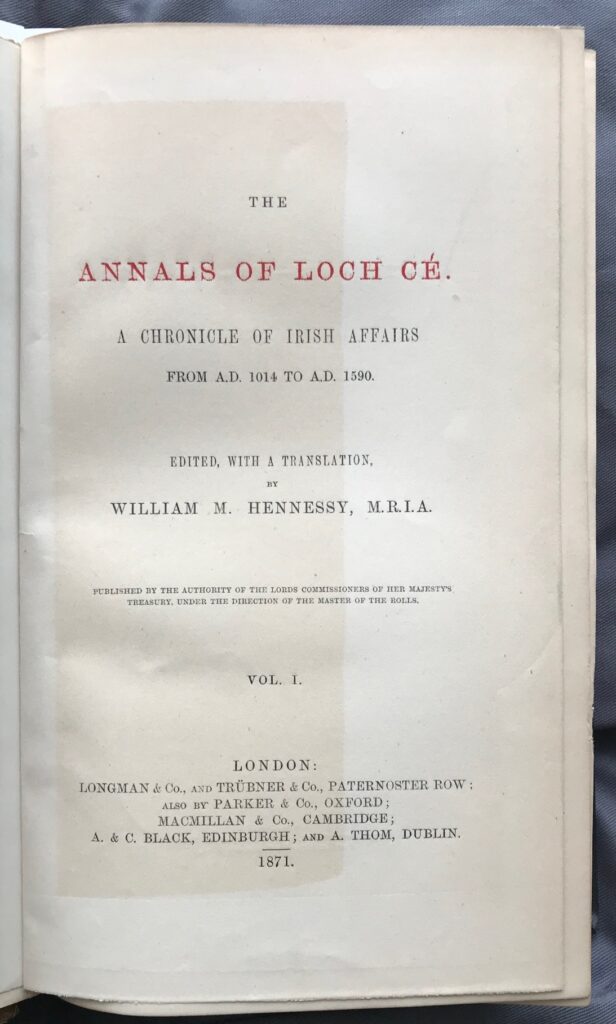

Evidence of commercial fisheries in Ireland can be found in the Irish Annals from late thirteenth century. It shows how fishermen from along the Irish coast travelled to the Island of Man to fish.

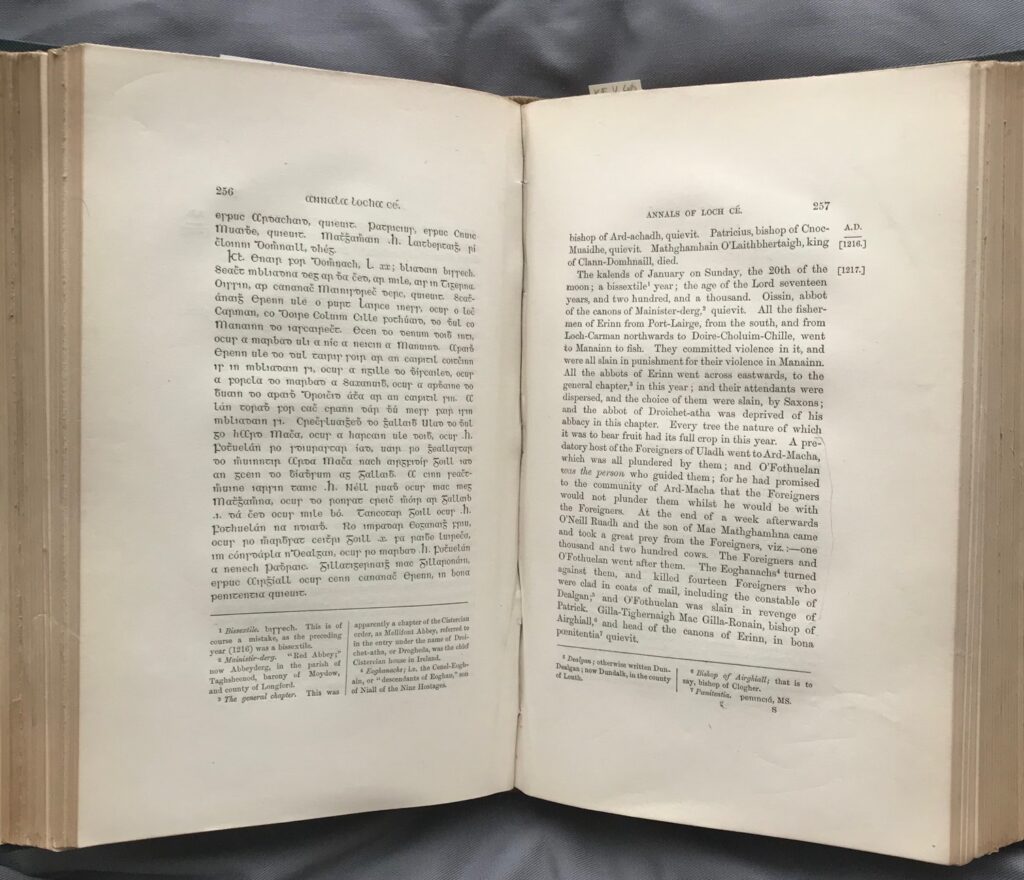

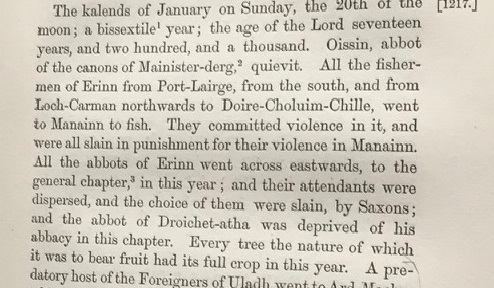

All the fishermen of Erinn from Port-Lairge, from the south, and from Loch-Carman northwards to Doire-Choluim-Chille, went to Manainn to fish.

The Annals of Loch Cé. a Chronicle of Irish affairs from A.D. 1014 to A.D. 1590. Edited with a translation William M. Hennessy 1871 P001204269

From the fourteenth century onwards, the coasts of Ireland were fished by foreign fishing fleets, particularly those from England, Wales, Scotland, Brittany, Spain and the Netherlands.

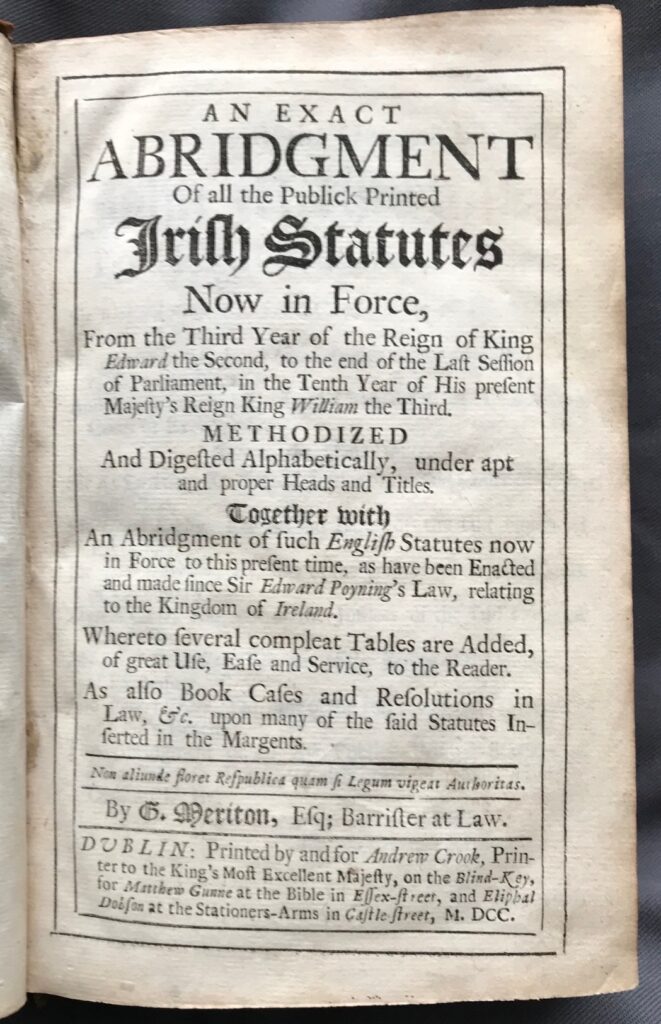

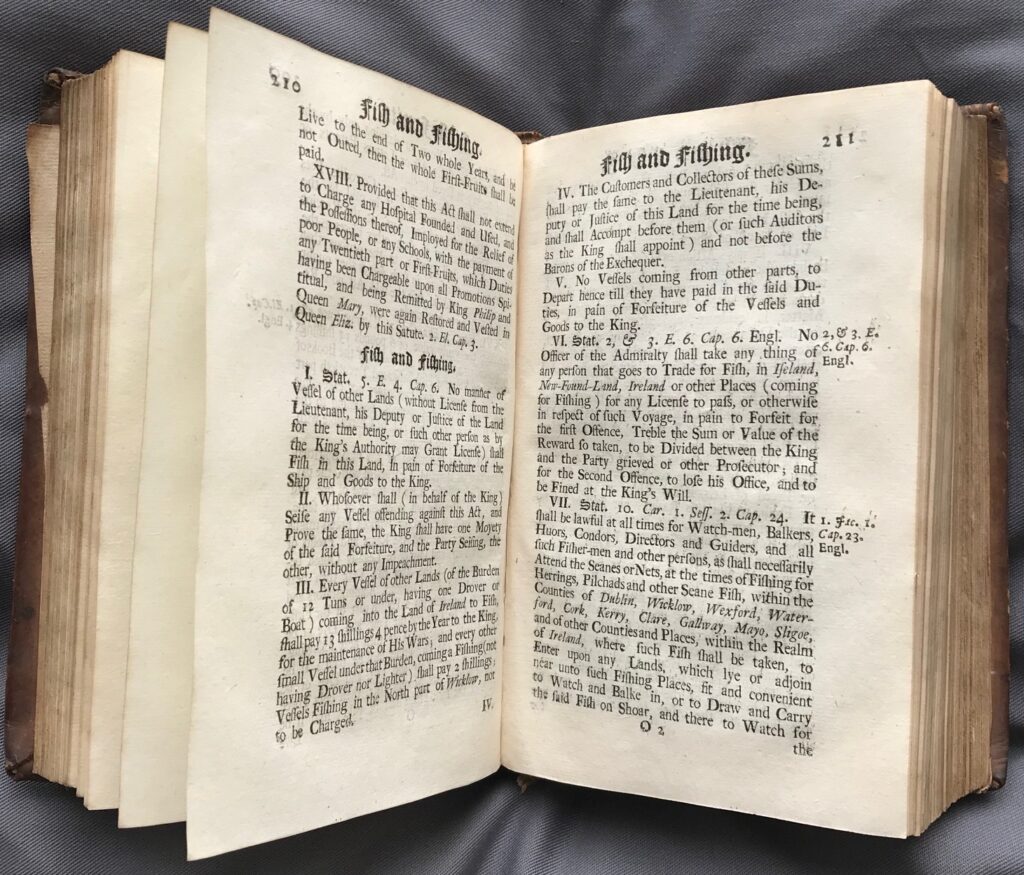

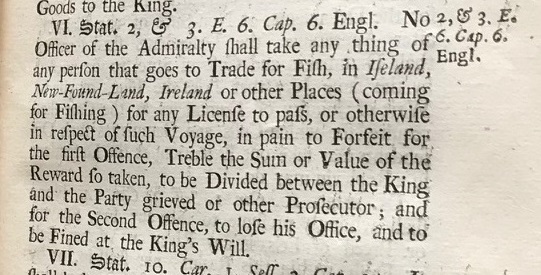

In 1465 an Act of Parliament was passed to prevent foreign fishing ships, who were fishing in Irish waters, offering support to the King’s enemies. They needed to get a licence, and, if obtained, would pay a tax. Many of the foreign fishermen would divert to fish off the coast of Newfoundland in the sixteenth century.

An Exact Abridgment of All the Publick Printed Irish Statutes ... G. Meriton 1700

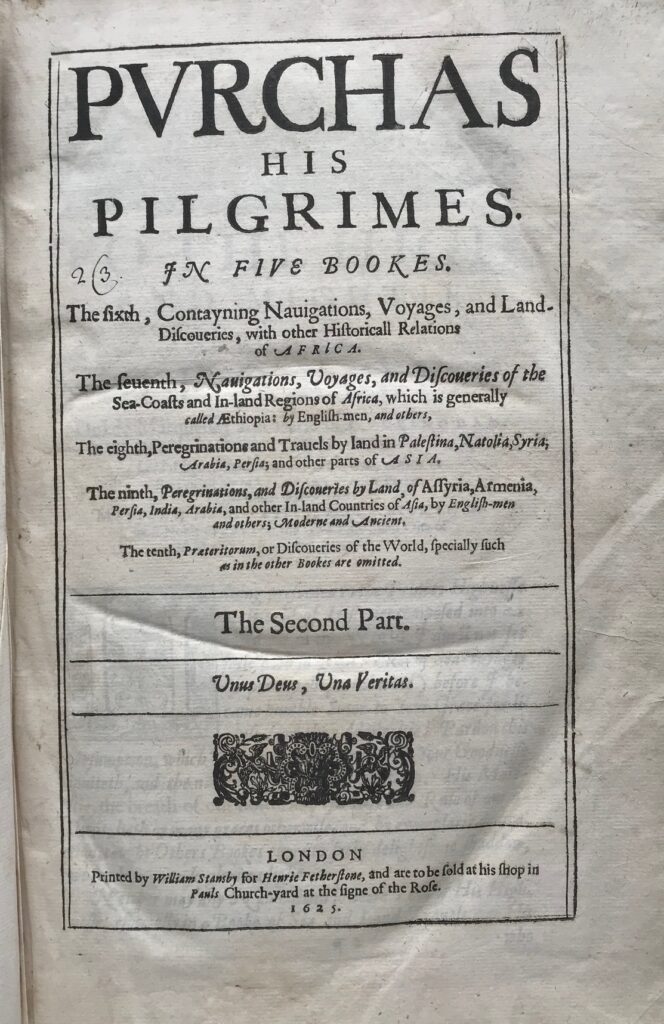

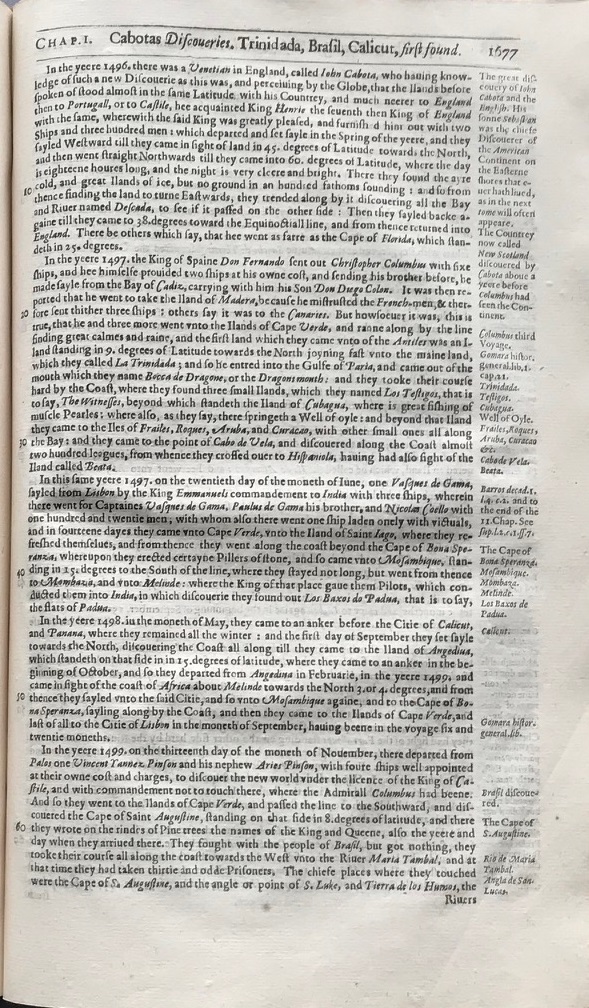

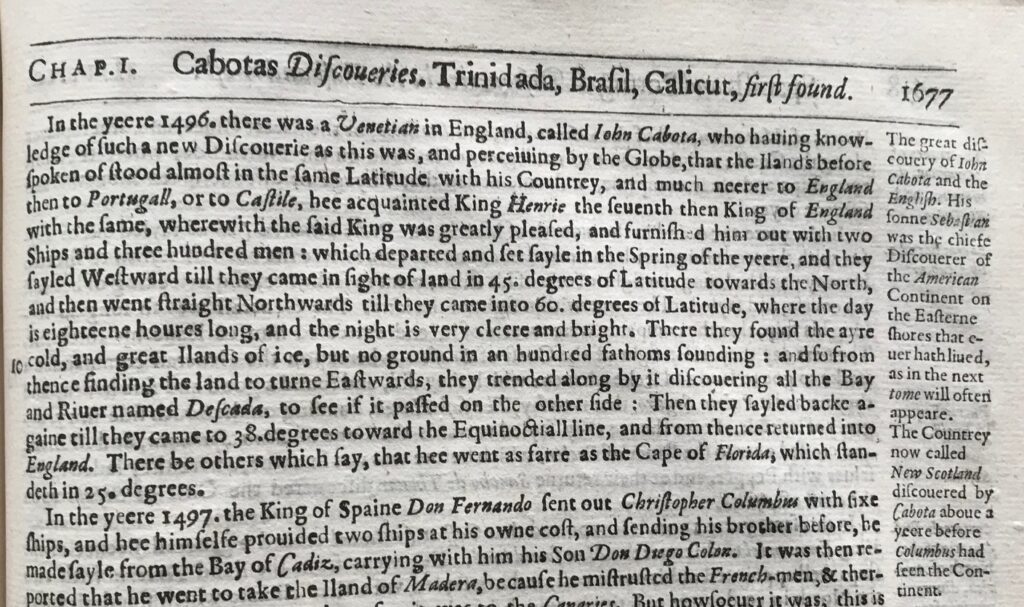

In 1496 Italian explorer John Cabot (Giovanni Chaboto) and his sons were granted permission by Henry VII to sail and explore the world under Henry’s banner.

During one of those voyages in 1497 Cabot re-discovered a ‘new found land’. It is said that his men were able to catch cod simply by dipping a basket into the sea!

The discovery of these rich fishing grounds at Newfoundland attracted a lot of attention from Western European countries.

By 1510 fishermen regularly made an annual trip to Newfoundland to fish without settling there. Most of the fishermen in this so-called migratory industry were Breton, Norman and Portuguese, with very few being Englishmen.

Purchas his pilgrimes. In five bookes... Samuel Purchas 1625-1626 P00114701x

By the sixteenth century more people in Europe were working in fishing than in any other occupation except farming.

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the government realised that men who had navigation and fishing skills would be of great benefit to the navy.

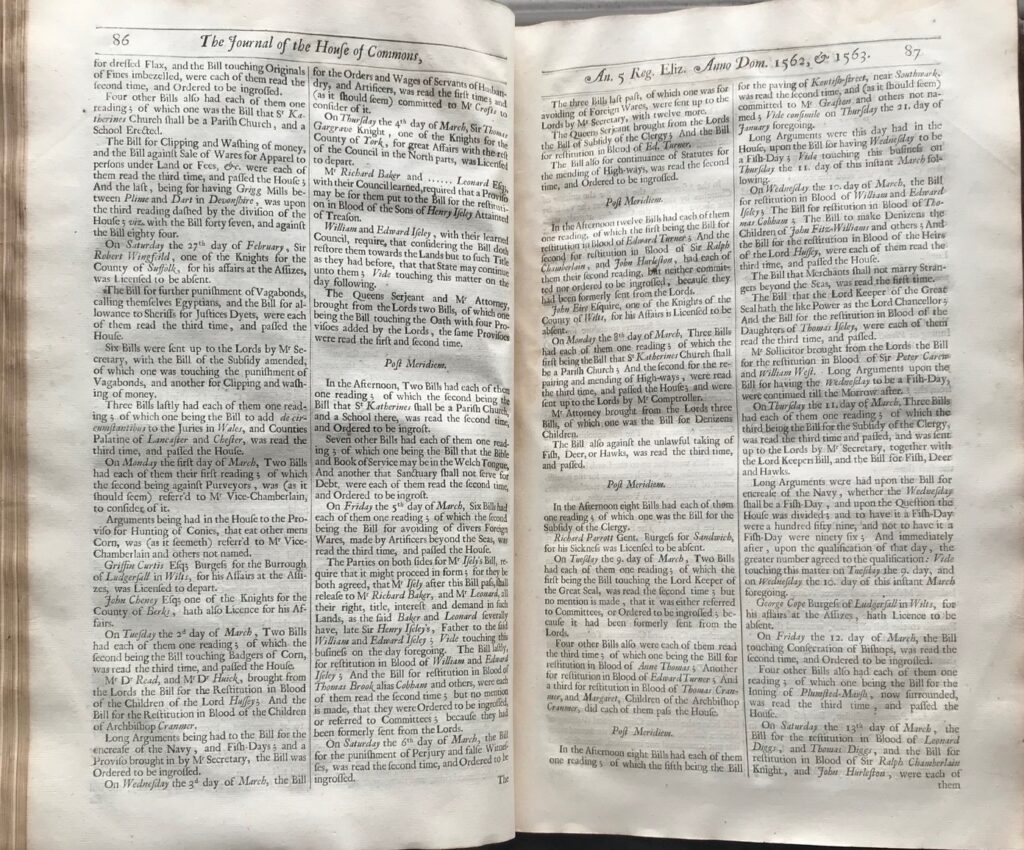

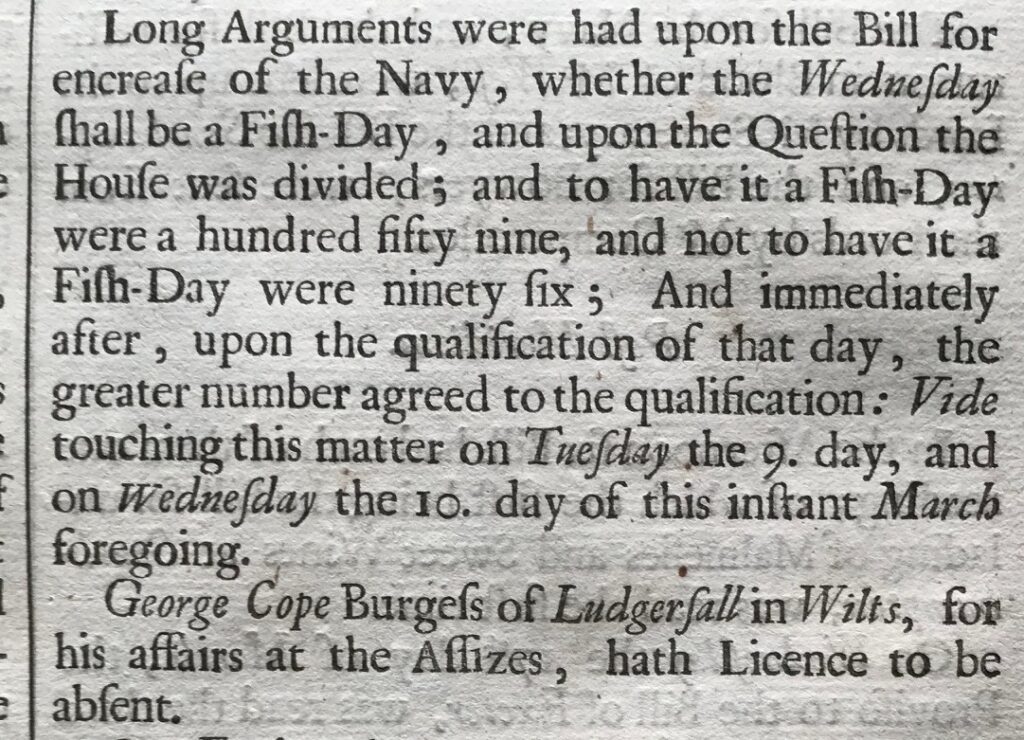

In 1563 Elizabeth I’s chief advisor William Cecil proposed a bill stating that people should eat fish on Wednesdays on top of the usual Fridays and holy days. If the bill passed, it would support strengthening the navy, as well as the fishing industry. Cecil’s speech was called:

Arguments to prove that it is necessary for the restoring of the navy of England to have more fish eaten and therefore one day more in the week ordained to be a fish day, and that to be Wednesday rather than any other.

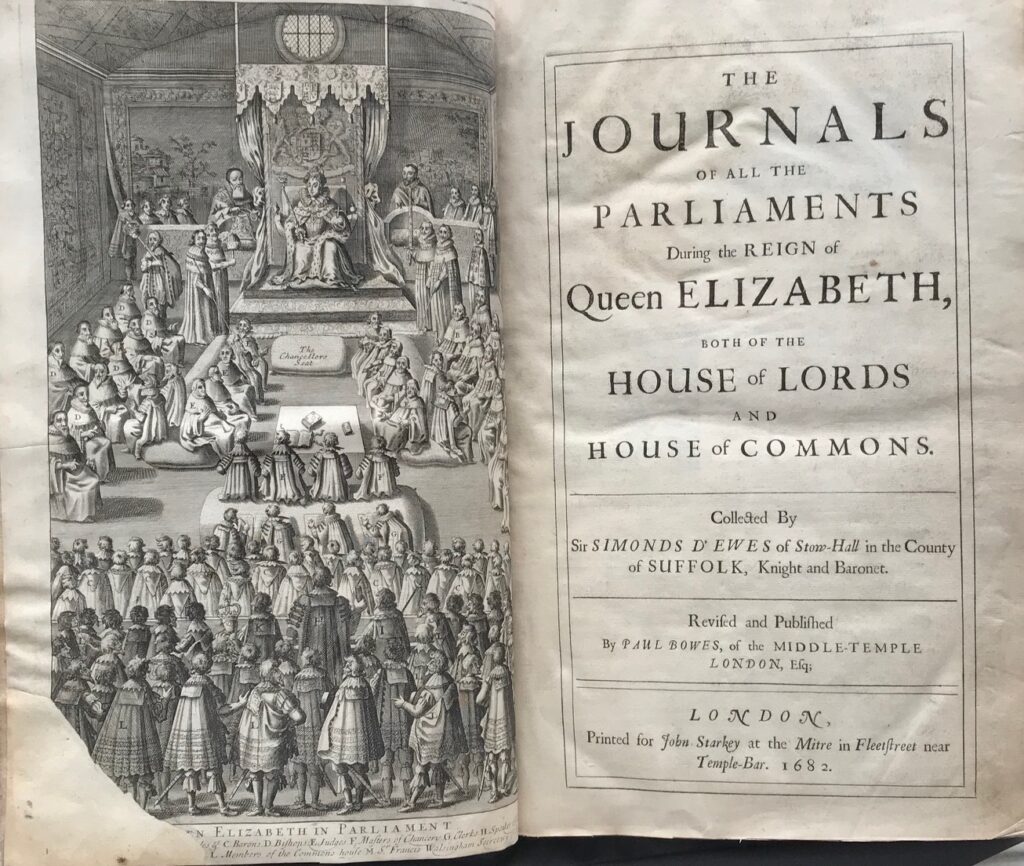

The Journals of All the Parliaments During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth, Both of the House of Lords and House of Commons. … Simonds D'Ewes 1682 P001127647

Ireland was not part of the migratory fishing industry until the late-1600s. It was then that Irish coastal towns were being visited by English ships on their way to Newfoundland. They supplied provisions for their journeys.

From the early 1700s these ships also hired Irish people to work in the fisheries overseas.

In the early 1800s, after nearly 300 years of migratory fishery, fishermen started to settle in small communities for the spring and summer seasons. A resident industry was established.

England played a major role in the resident fishing industry by sending fishermen, both English and Irish, to settle and work.

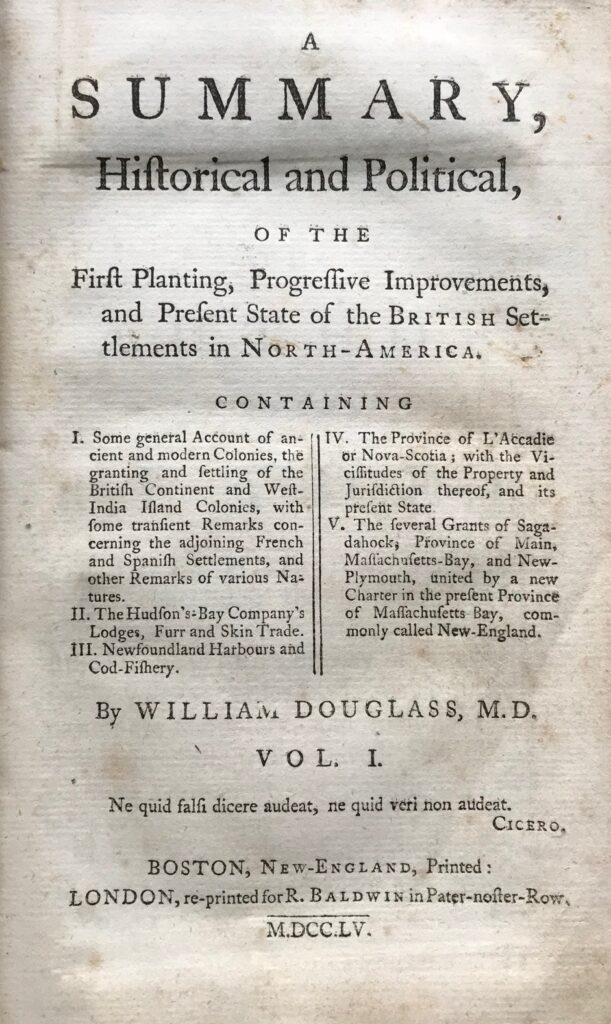

A summary, Historical and Political, of the First Planting, Progressive Improvements, and Present State of the British Settlements in North-America ... William Douglass 1755 P001146714

By the 1770s large commercial companies were fishing near and (very) far.

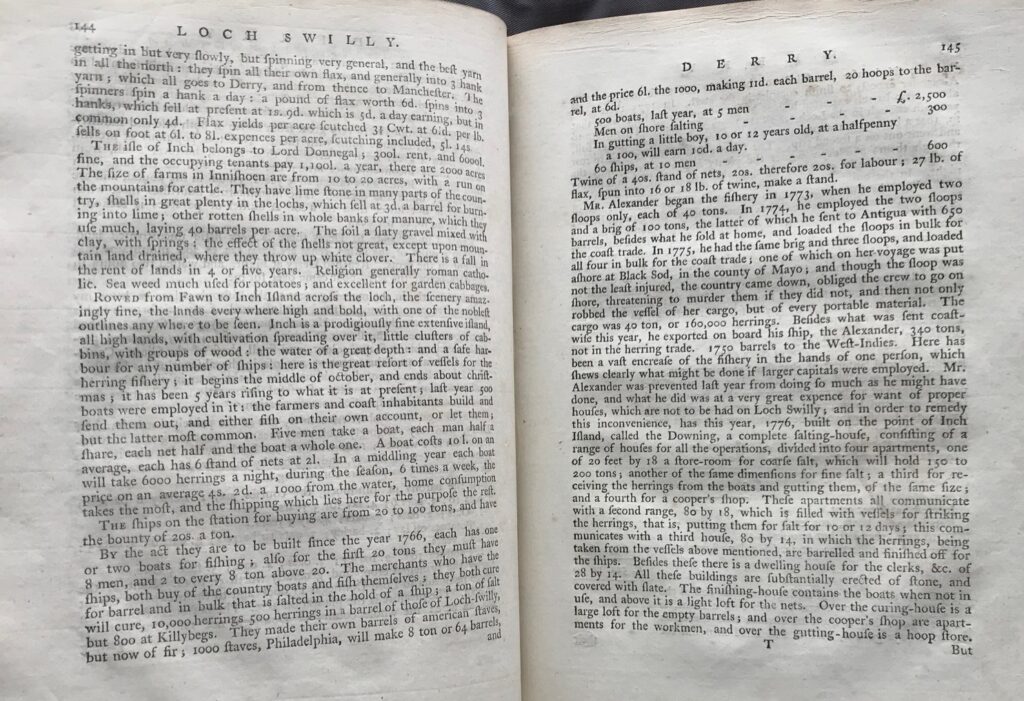

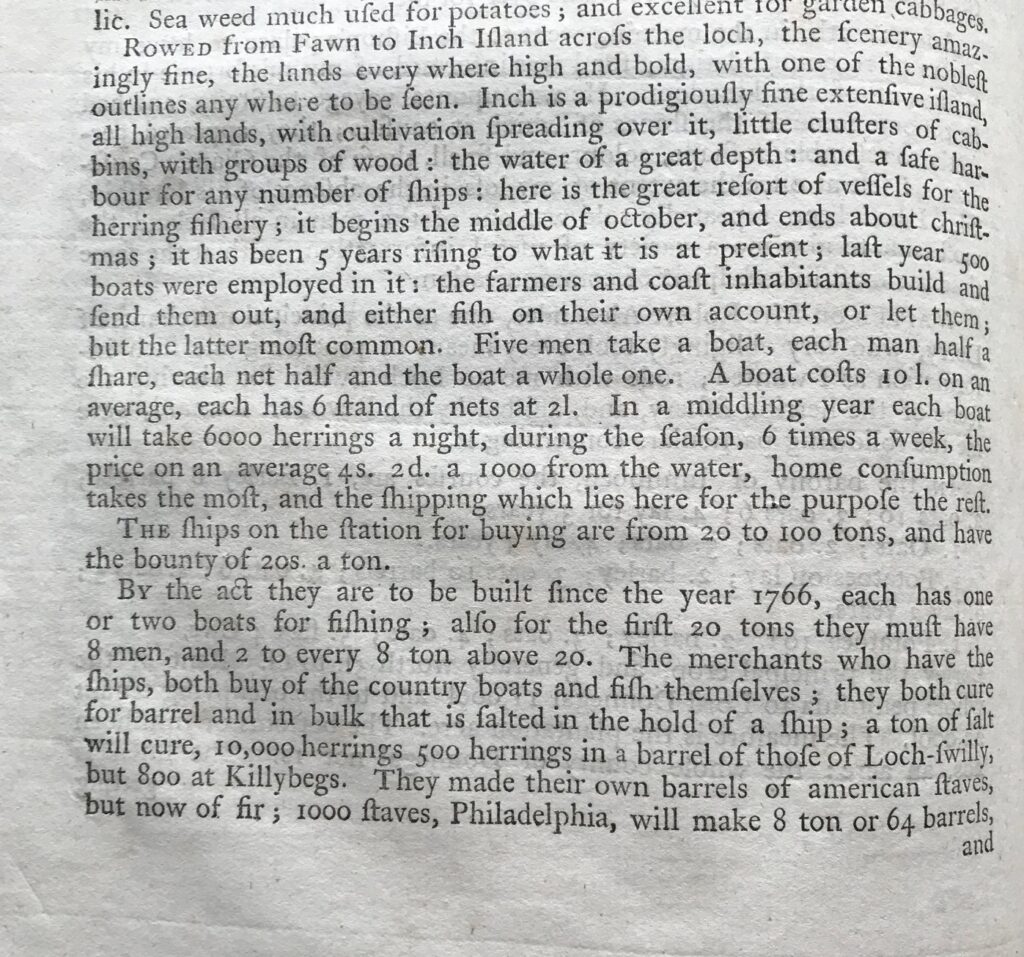

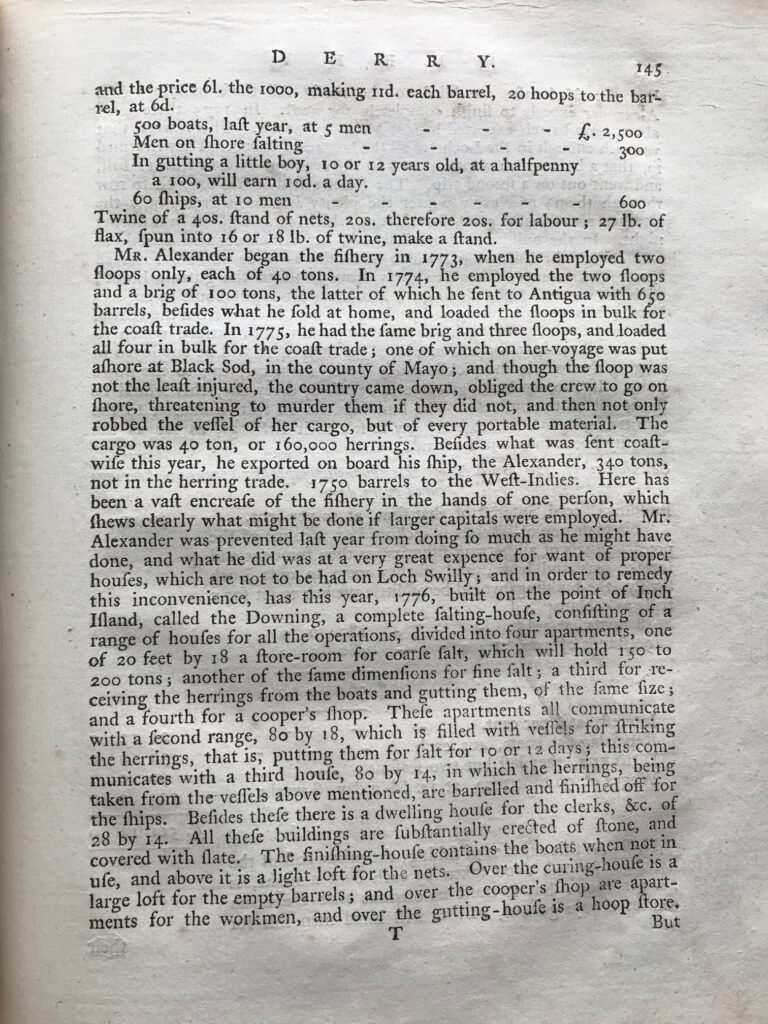

An example of one very large-scale local fishing company operating on Lough Swilly, Co. Donegal can be found in Arthur Young’s description of his tour of Ireland:

Here is the great resort of vessels for the herring industry; it begins the middle of October, and ends about Christmas . . . last year 500 boats were employed in it: the farmers and coast inhabitants build them and send them out.

It was claimed that boats from all over Europe came to fish in Lough Swilly at that particular time. In 1775,

the number of herring in the Lough was so great, the fellows said it was difficult to row through them.

A Tour in Ireland; with general Observations on the present State of that Kingdom: made in the Years 1776, 1777, and 1778. And brought down to the End of 1779. Arthur Young 1780 P001128171

In the present day there are thirty-five coastal fishing ports in Northern Ireland. Most of these support a handful of small inshore fishing boats.

Lough Neagh, the largest freshwater lake in the UK, supports ca 250 fishermen who fish for eel, pollan, trout, perch, roach, bream and pike.

The majority of the catch in Northern Ireland, both freshwater and salt water, is exported.

However, more and more local restaurants and businesses increasingly include locally caught fish in their menus.