This exhibition forms part of the year’s celebrations to mark the Library’s 250th anniversary.

It has been supported by the Paul Mellon Centre.

Click on the images to view a stand-alone version.

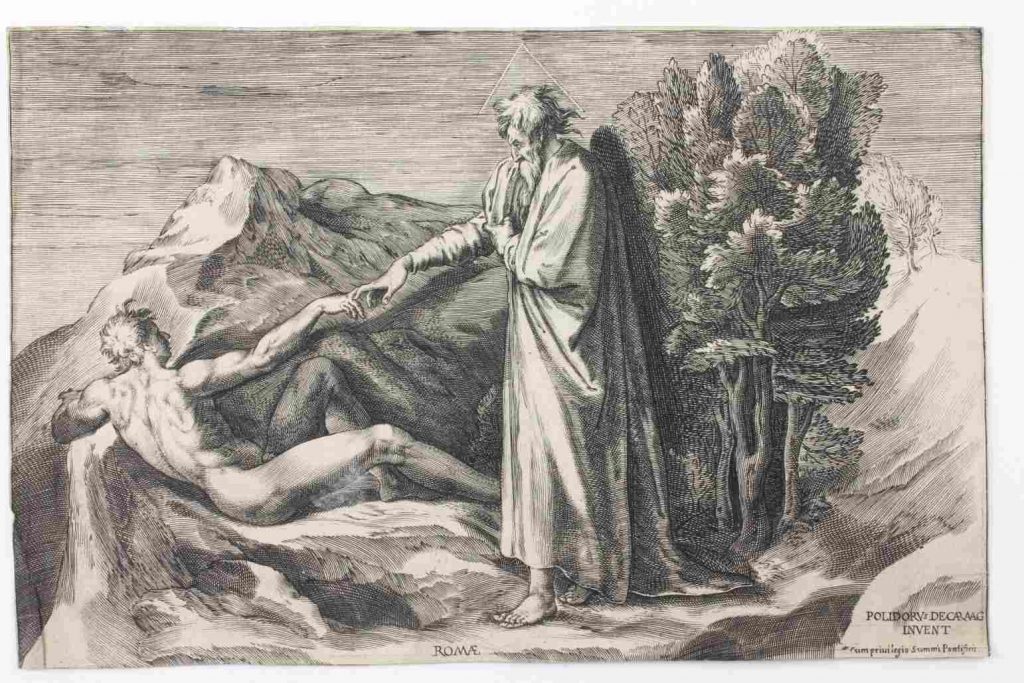

Reproductive engraving after a monochrome fresco of the creation of Adam Cherubino Alberti (1553-1615), after Polidoro da Caravaggio (c.1499-c.1543) Rome c.1570-90 P002477892

In this engraving, the printmaker Cherubino Alberti has reproduced a fresco, a mural painting, that was painted on the outside of a building. The fresco started to decay a few decades after it was made.

The original fresco was executed in various tones of a single colour. It was intended to evoke the character of another medium: relief sculpture.

To recreate the different tones, Cherubino used both overlapping lines and lines graduating in thickness, giving the effect of contour.

The effect of modelling in three dimensions through tone is known as ‘chiaroscuro’ (‘light-dark’). The result is the complete opposite of the bright clarity of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel. Here, the creation of mankind is a mysterious event, taking place in a world not yet fully illuminated.

La Historia d’Italia Francesco Guicciardini (1483-1540). Venice : Nicolò Bevilacqua 1568 P001451630 Two friezes of sea monsters Johann Theodor de Bry (1561-1623), after Giovanni Andrea Maglioli (fl.1580-1610) Frankfurt, c.1588-1623 P002478003

On the first page of La Historia d’Italia, the Florentine historian and statesman, Francesco Guicciardini, describes history as ‘a sea whipped by winds’ (uno mare concitato da’ venti).

The phrase sums up the social, scientific, religious and political unrest that was felt at the time. This unrest happened at the same time as the rise of Mannerist art, and can be seen in the artwork.

Guicciardini’s history of the early years of the sixteenth century shows how people in control failed to create order in society.

Printmakers and designers like Giovanni Andrea Maglioli relished the opportunity to imagine the beasts that populated those newly discovered windy seas.

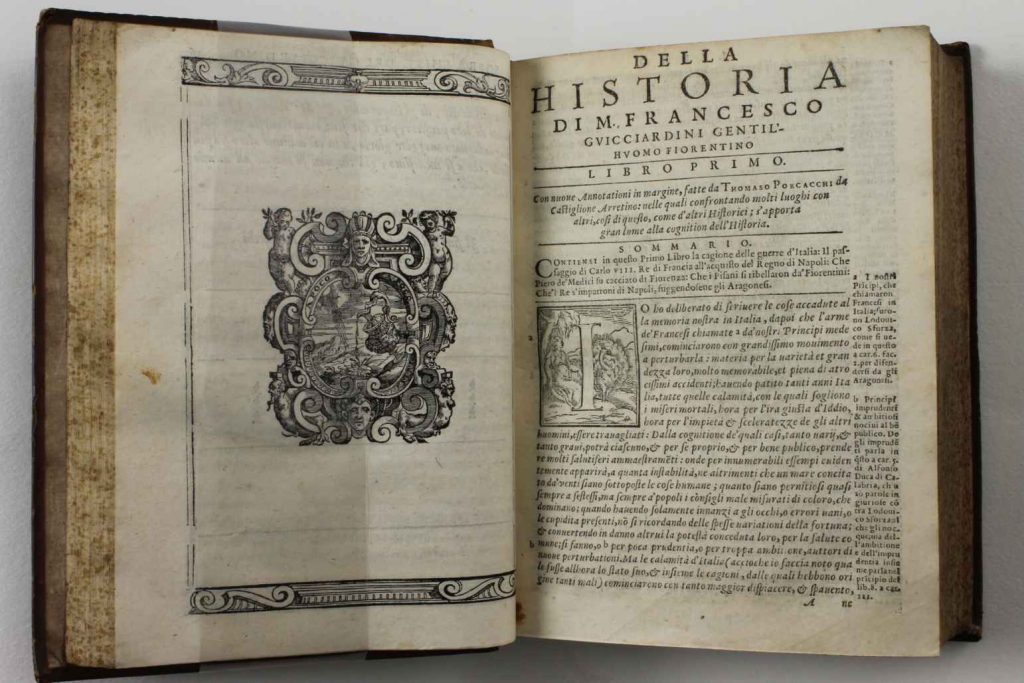

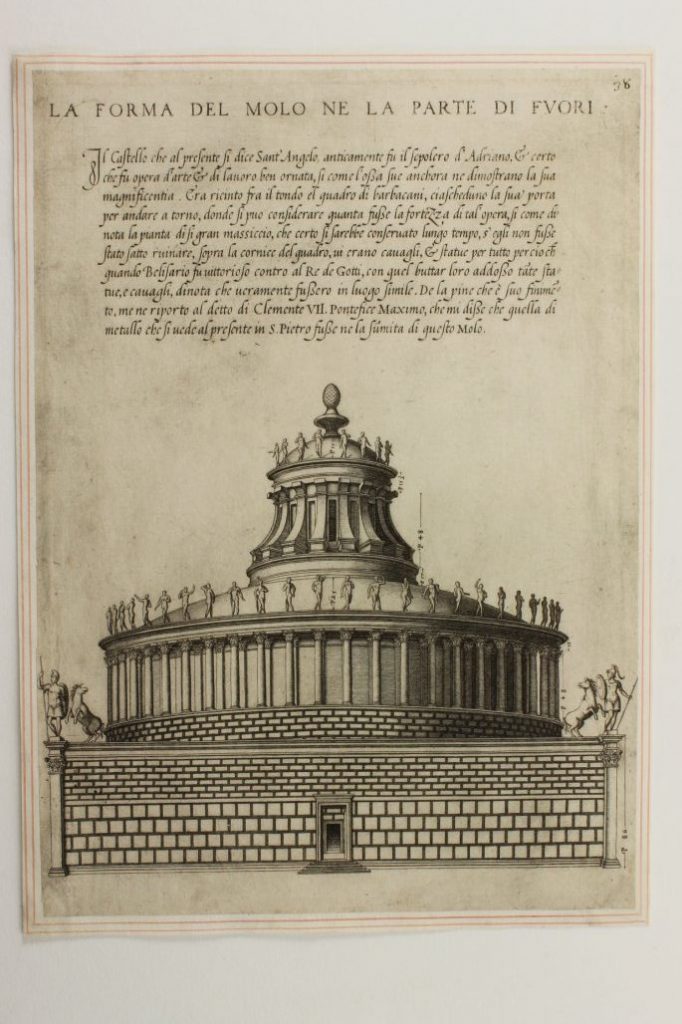

Engraving of a reconstructed elevation of the mausoleum of Emperor Hadrian Mario Labacco (c. 1530-after 1587), after Antonio Labacco (c.1495-after 1567). Rome 1552 P002477794 Etching of the catafalque of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in the Oratorio del Gonfalone, Rome. Girolamo Rainaldi (1570-1655) Rome 1589 P002477795

Copper plate engravings offered new possibilities for architects, who had previously only used woodcuts to spread their ideas.

In the first print, the mausoleum of the Roman Emperor Hadrian († 138 AD) is imaginatively recreated. It was based on the ruins that survived in the sixteenth century. To this day, the mausoleum is known as the Castel Sant’Angelo.

Labacco was one of the first to illustrate architecture in engraving, allowing for greater detail and three-dimensional shading.

In the second print, the teenage Girolamo Rainaldi illustrates his own lavish catafalque (funeral platform) for the art patron Alessandro Farnese. The etching was used to promote the catafalque in April 1589, a week before the funeral ceremony itself.

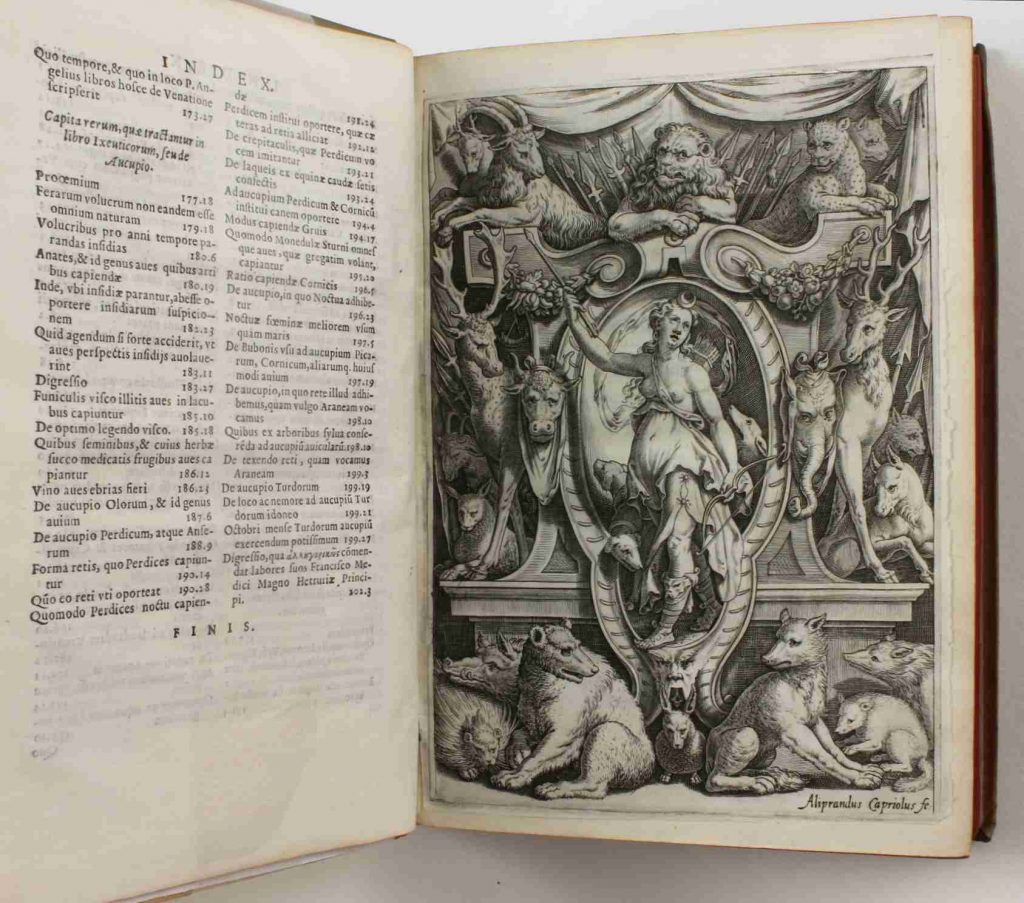

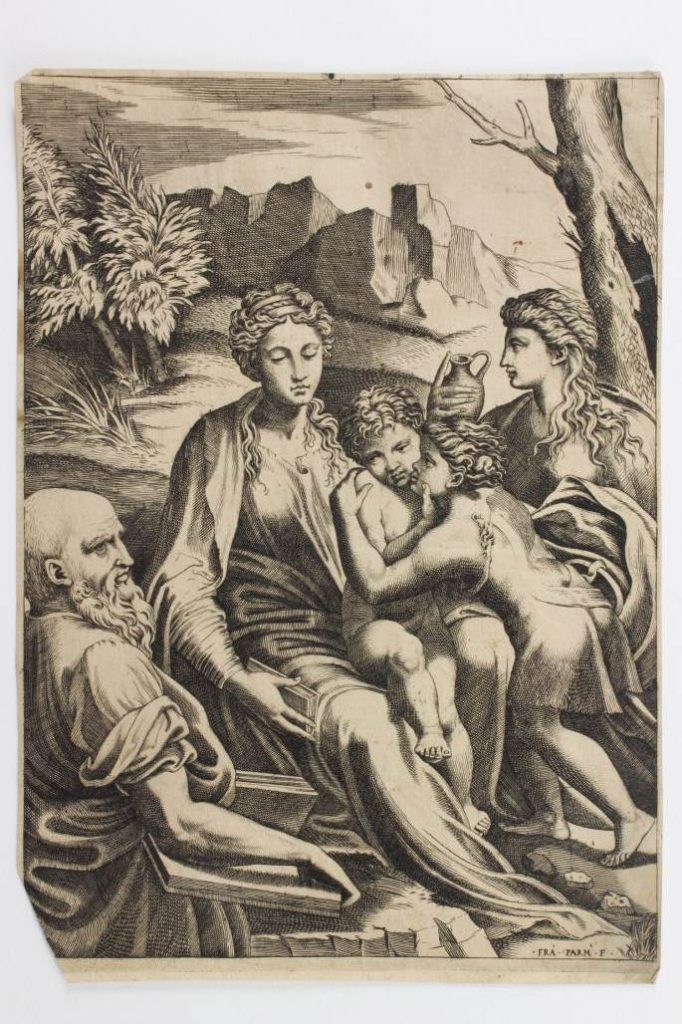

Reproductive engraving of the Madonna and Child with Saint Zechariah Anonymous engraver after Giulio Bonasone (c.1510-after 1576), after Parmigianino (1503-1540) Bologna or Rome After 1543 P002477889 Illustration of Diana for Pietro Angeli da Barga’s Poemata Omnia Aliprando Caprioli (fl. 1575-1799) Rome 1585 P001358991

The originality and expressiveness of Mannerist paintings sometimes gained them celebrity status, and prints made after them added to, and prolonged their fame.

Here an anonymous printmaker has loosely copied Parmigianino’s Madonna and Child with Saint Zechariah (c.1530–1533), now in the Uffizi in Florence. In the late eighteenth century, the art historian Luigi Lanzi noted that it was the most copied painting in the gallery.

Works from antiquity could achieve even greater fame, such as the sculpture known as the Diana of Versailles. Aliprando Caprioli adapted this sculpture to illustrate Pietro Angeli’s poem on the art of hunting, his Cynegetica (1561).

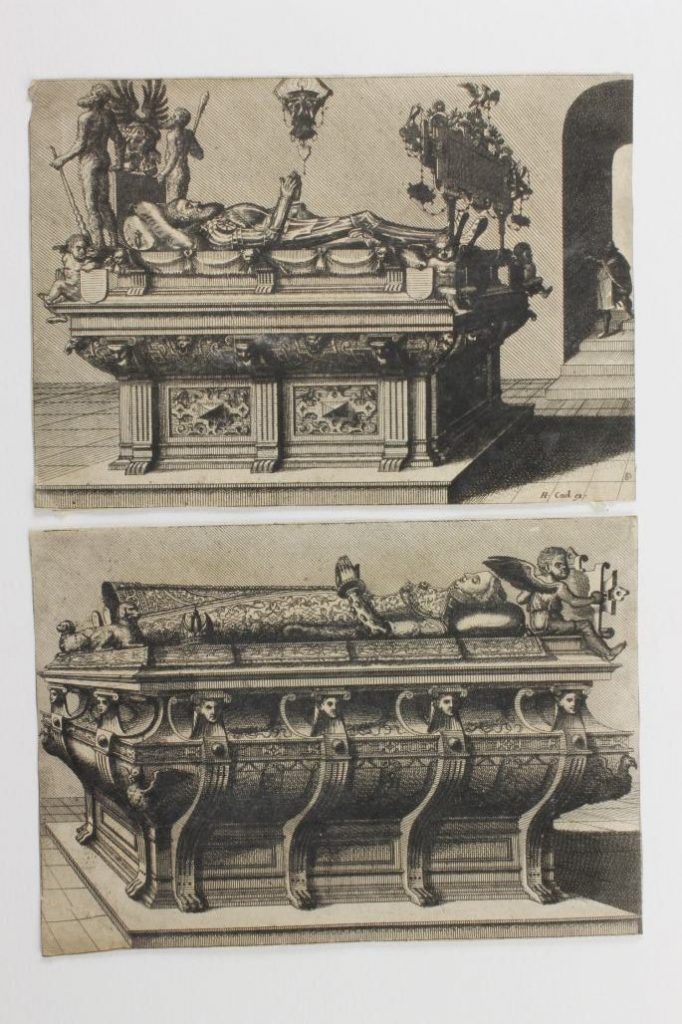

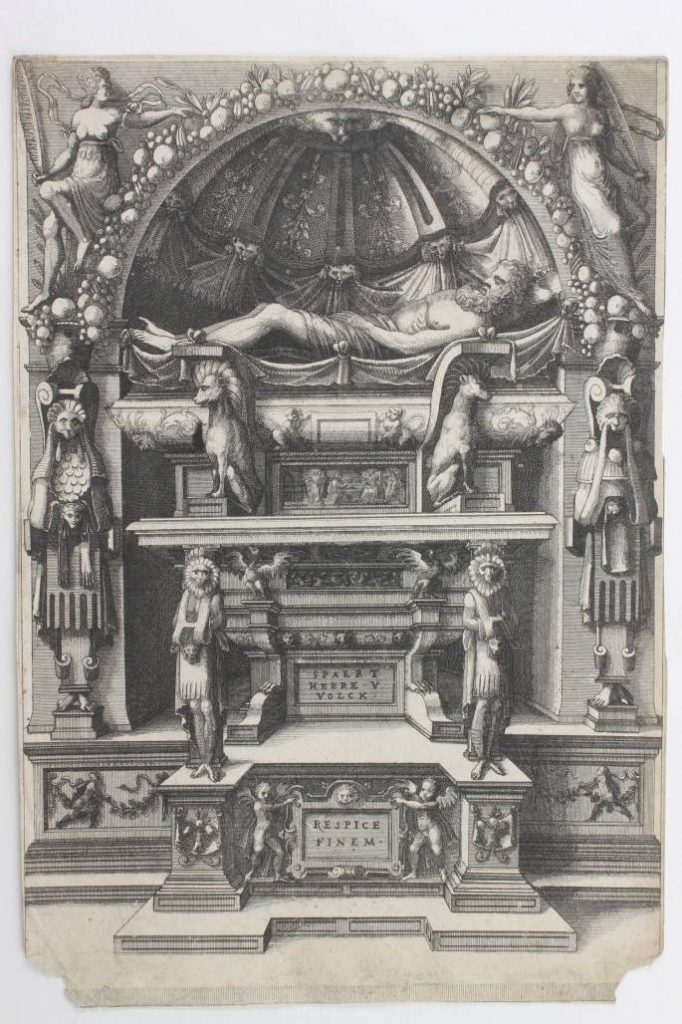

Plate from Vlakdecoratie en grafmonumenten Jan van Doetechum (fl 1554–c. 1600) or Lucas van Doetechum (fl. 1554; d before 1584), after Cornelis Floris (c.1513-1575) Antwerp 1557 P002477791 Two prints from Cœnotaphiorum Jan van Doetechum (fl 1554-c. 1600) or Lucas van Doetechum (fl. 1554-d. before 1584), after Hans Vredeman de Vries (c.1527-c.1606) Antwerp 1563 P002477793

The strangeness and richness of Mannerist printmaking arguably reached its peak with the ornamental etchings that came from the Antwerp publishing house Aux Quatre Vents (‘At the Sign of the Four Winds’).

The prints shown here were produced by Dutch brothers Jan and Lucas van Doetechum.

These were all for funeral monuments, and all highly unconvincing as designs. The type of monuments that they depict would soon be vandalised during the riots of 1566. The riots contributed to the decline of Antwerp’s importance as the financial centre of Europe.

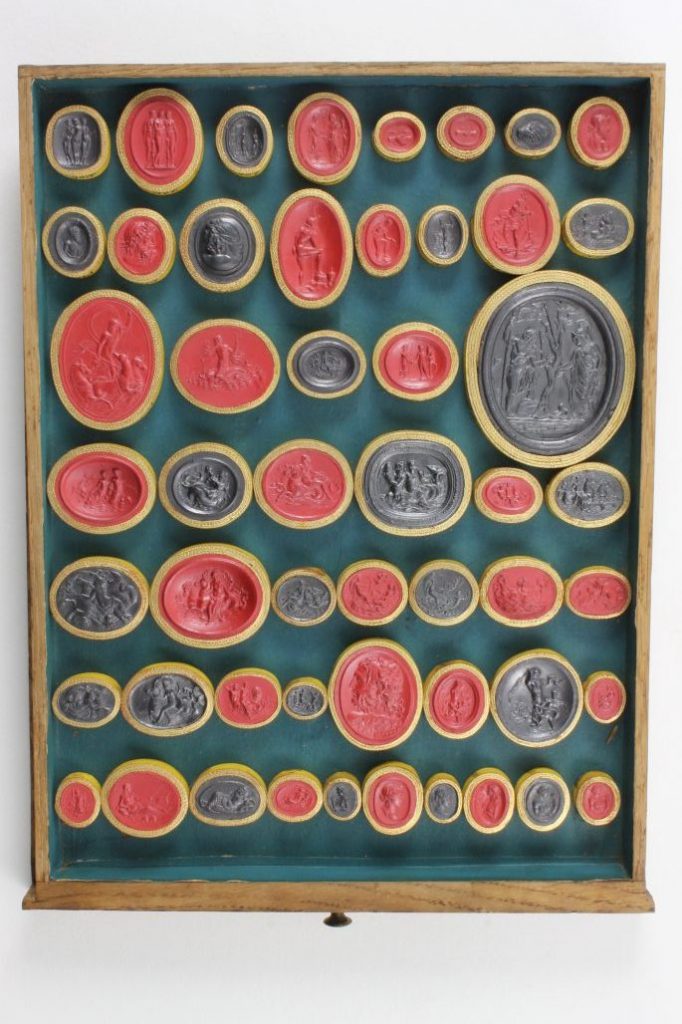

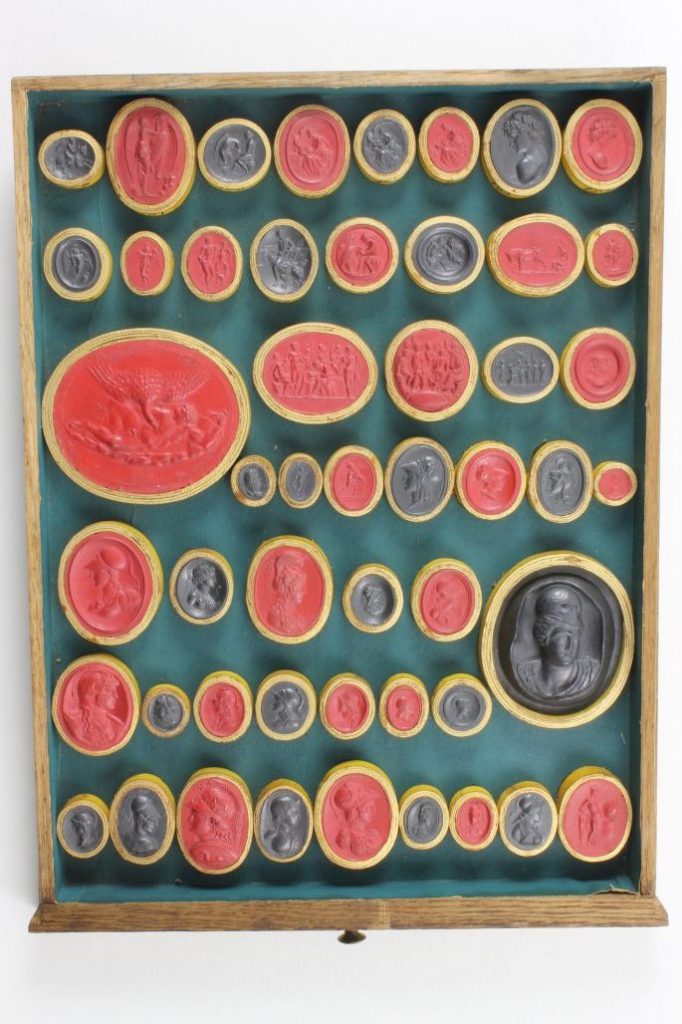

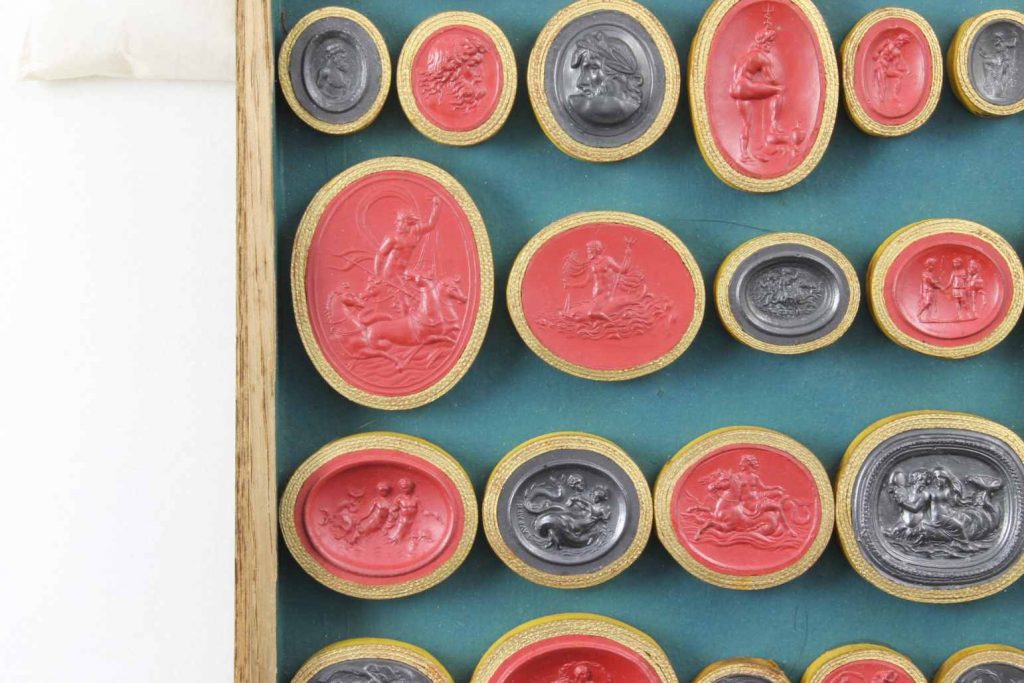

Impression no. 321: Neptune Driving Four Hippocamps James Tassie (1735-1799), after Valerio Belli (c.1468-1546) Italy, 16th century (original); London, c.1775 (reproduction) Tassie gem impressions, drawer D Impression no. 202: The Punishment of Prometheus James Tassie (1735-1799), after Giovanni Bernardi (1494-1553), after Michelangelo (1475-1564) Italy, 16th century (original); London, c.1775 (reproduction) Tassie gem impressions, drawer D

These two drawers are from Archbishop Robinson’s own collection of impressions after engraved gems, which he left to the Library.

Unlike printmaking, gem engraving had a direct link to classical antiquity.

It followed more closely the artistic examples of the ancient world. Gem engraving also had a more select audience than for the more accessible medium of print.

The Calumny of Apelles Giorgio Ghisi (1520-1582), after Luca Penni (c.1500/1504-1557) 1560 Engraving P002477891

This print finds it origin in a lost ancient Greek painting by Apelles which showed his own escape from slander.

Penni painted the figure of Apelles as a young child to emphasise the victim’s vulnerability.

The other figures in this allegorical print either represent vices or virtues, or roles of power and powerlessness. Calumny, or slander, surrounded byEnvy, Treachery and Deceit drags the innocent Apelles before the judge, King Midas.

Flanked by Ignorance and Suspicion King Midas is shown with ass’s ears. The god Apollo turned his ears into ass’s ears, when Midas chose a satyr’s music over Apollo’s. In this case he is shown as a symbol for the inability to make sound judgements.

Time is shown to the left, bringing in his daughter, Truth, to reveal the actual facts. Repentance is standing in the doorway.

Scene of a Judgment Battista Franco (c.1510-1561) Mid-16th century Etching and engraving P002477758

This print is a fantasy subject, as it does not tell a particular story from history or mythology.

The author is the Venetian-born painter Battista Franco, who promoted the new medium of etching.

In this print Franco is more interested in showing gestures and antique decoration than telling a specific story. Viewers can decide for themselves what the scene is about, just as the figures in the print are doing.

Franco’s source may be some version of the ‘Calumny of Apelles’ theme mentioned earlier.

The Holy Family with St Anne, bathing the infant Christ in a basin Battista Angolo del Moro (c.1515-1573) c. 1570 Etching P002477760

Battista Angolo del Moro was one of the most successful painters in Verona, and he turned to the new medium of etching with great success.

This is particularly fortunate, because his paintings were mostly murals, and have been lost due to age and the weather!

This etching is made after a drawing by Giulio Romano.

Battista was trained by a painter who used designs by Giulio Romano to paint wall paintings in Verona Cathedral. This may explain how Battista found the source for this work.

The medium of etching, with its fluid lines, was well suited to preserving the effect of drawings. Etchings ensured that works of famous artists like Giulio Romano were kept safe for the future.

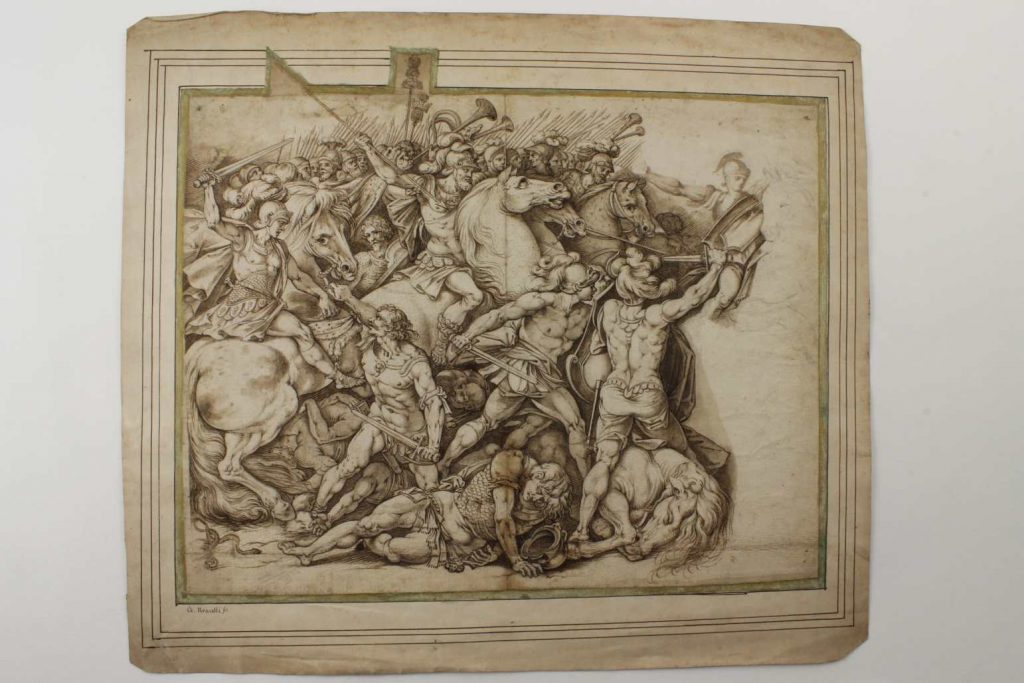

The Army of Tullus Hostilius defeating a Tribe of Etruscans. Follower of Giuseppe Cesari, called Cavaliere d'Arpino (1568-1640) First quarter of the 17th century Pen and ink with wash P002477999

This print is a highlight of the Rokeby Collection that has not previously been recorded, and it is shown here for the first time.

The drawing follows the design of a fresco in the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome, painted in 1597-1601. It may have been made either after the fresco itself or after a preliminary drawing by the artist, Giuseppe Cesari.

The scene depicts the equestrian army of the legendary third king of Rome, Tullus Hostilius, defeating the Etruscan warriors of the Veii tribe.

The bearded figure between the two horsemen on the left is a self-portrait of Cesari. In the original fresco, the figure looks up to the left, but in this version of the scene, he seems to look directly out at the viewer.